The flood of farmed shrimp onto the global market has even overseas shrimp farmers complaining about low prices. In the U.S., shrimp fishermen can sometimes barely pay for their fuel when they make a trip. In states like Texas, which once boasted 2,500 licensed shrimpers, the number is now below 1,000.

The main thing U.S. shrimpers have going for them is quality and their “Gulf shrimp” brand. But when restaurants sell farmed shrimp falsely labeled as wild caught U.S. shrimp, that advantage is lost.

“I think there may be a lot of people out there who think they’ve eaten Gulf shrimp, who’ve never actually tasted it,” says Dave Williams, a commercial fishery scientist and founder of SeaD Consulting. Williams and his team have developed the Rapid ID Genetic High-accuracy Test (RIGHTTest) to determine the origins of seafood – and have found rampant fraud on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

On a Dec. 2 webinar, “Is it local? Navigating Seafood Mislabeling,” hosted by the Local Catch Network, Williams described taking his company’s technology to the Louisiana Shrimp and Petroleum Festival, which has been held annually for almost one hundred years.

“We took five samples from vendors there and found four of them selling imported farmed shrimp,” says Williams. “Only one was selling Gulf shrimp. “Then we then went to the National Shrimp Festival in Gulf Shores, Alabama. That one has rules that they have to sell Gulf shrimp, but they’re not enforced. Again, we found 80 percent imported farmed shrimp.”

When Williams and the SeaD Consulting team took their rapid DNA testing to restaurants, the results showed that in 44 restaurants tested in Biloxi, only eight were selling Gulf shrimp as advertised. “Many were selling ‘Royal Red’ shrimp, which is an FDA protected brand name, and we simply asked them where the shrimp were coming from. They told us, Argentina. That’s a different shrimp. That’s fraud.”

Trade groups like the Southern Shrimp Alliance and the Louisiana Shrimp Association are paying attention to SeaD Consulting’s work. “There is no excuse for passing this cheap unhealthy shrimp off as locally caught shrimp. Restaurants, food vendors, festivals and anyone else that sells shrimp to the consumer in a fraudulent manner should be fined and dealt with accordingly,” stated an October 2024 press release from the Louisiana Shrimp Association, which highlighted the SeaD consulting findings.

In 2024, Louisiana state Sen. Patrick Connick got a bill passed that would crack down on seafood mislabeling. CBS affiliate WAFB-TV in Baton Rouge reported that Connick pointed to a recent admission by the popular Biloxi, Miss. restaurant Mary Mahoney’s Old French House as proof of the need for tighter enforcement. According to WAFB, one of the owners plead guilty to buying over 29 tons of foreign seafood between 2013 and 2019, passing it off to customers as Gulf of Mexico seafood.

“That’s deceptive trade practices,” Connick told WAFB. “You’re buying an inferior product; you’re putting a quality label on it, and you’re lying.”

The Louisiana Department of Health will enforce the new legislation, which requires sellers to display a disclaimer on their menu if their product came from outside of the United States. Connick said this law will take effect in January 2025 and businesses who violate the rules could face fines up to $2,000.

“They’ll start getting hit with fines and they’re going to change their ways,” he said. “If you want to buy the product you can. We can’t prevent these products from coming in, but we can prevent them from using our heritage and culture on product when it’s not.”

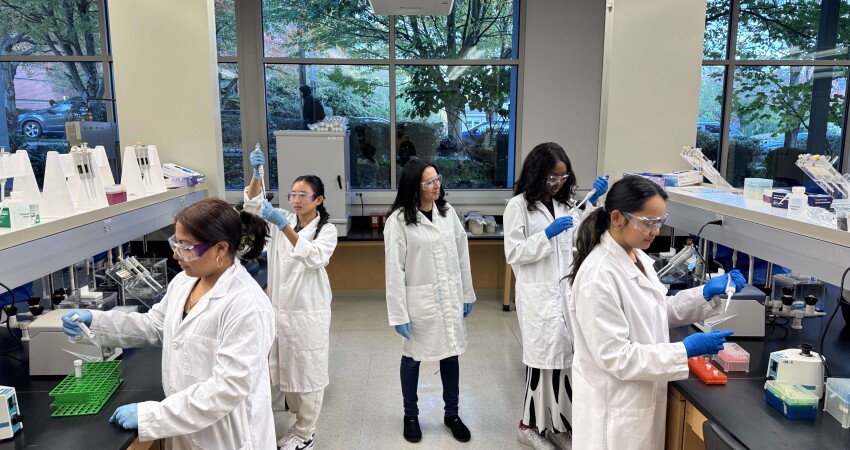

Williams notes that SeaD Consulting started to develop its technology to test red snapper. “But when we saw what was happening with shrimp, we changed our focus to help the industry,” he said. “We owe our success to Dr. Prashant Singh; he’s our genius. We hold the patent with him on the rapid genetic test, which is accurate with even a small sample. You could take a sample from a cooked gumbo, and it would still work. What we’d like to do is get the health departments in the parishes trained to start using the test and hold restaurants accountable.”

Besides highlighting the work of SeaD Consulting, the Local Catch Network webinar on Dec. 2 also featured a presentation by Dr. Tracie Delgado from Seattle Pacific University. Delgado presented findings from a two-year study that revealed rampant salmon mislabeling in Seattle area sushi restaurants, with farmed salmon substituted for wild salmon in one out of three restaurant samples.

“Focused analysis of only vendor-claimed wild salmon samples revealed a significant difference in the substitution of wild salmon with farmed salmon, with sushi restaurants having an overall higher mislabeling rate of 32.3 percent —10 of 31 samples mislabeled—compared to 0 percent in Seattle grocery stores,” said Delgado, describing the results of her tests.

She said, “Additionally, we found a significant difference in the occurrences of wild salmon being substituted with another salmon species, with sushi restaurants more likely to mislabel wild salmon at a rate of 38.7 percent compared to 11.1 percent in grocery store samples.

Also presenting for the Local Catch Network webinar was Julia Solomon Ensor, a staff attorney at the Federal Trade Commission, to talk about how the government is confronting the mislabeling issue. Ensor described the cops on the beat of seafood fraud, starting with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“There’s USDA COOL—Country of Origin Labeling,” she said. “As well as Customs and Border Patrol labeling requirements, the FDA, which splits jurisdiction with the FTC, and NOAA, which I think led some of the seafood fraud cases referenced earlier.”

Ensor notes that false seafood advertising falls under FTC jurisdiction and consumers can contact the agency if they spot a problem. “If you see a problem, you can report it at Reportfraud.ftc.gov. It helps if you identify the company that you think has a problem, and then tell us what kind of claim the company is making and why you think it’s false.”

Seafood fraud affects other fisheries besides Gulf shrimp and salmon and other presenters for the webinar spoke about whitefish mislabeling in New England. One mentioned a case of “Maine shrimp” (Pandalus borealis) being offered for sale in 2023, in spite of the fact that Maine has had a moratorium on its shrimp fishery since 2013.

The work of Williams and Delgado has gone a long way to raising awareness about the prevalence of seafood fraud in the U.S., with some unscrupulous restauranteurs and retailers pawning off cheap imports on consumers who want to support local fisheries and eat safe seafood. But Delgado notes that the fraud may begin at a point prior to the final sale, and that restauranteurs and retailers may themselves have been duped.

The work of protecting consumers and fishermen is ongoing. The RIGHTTest that SeaD developed, along with rigorous research by scientists like Delgado will help enforcement crack down on seafood fraud in the US. Improved traceability, greater public awareness, and stiffer penalties for mislabeling, will likely help honest suppliers and domestic fishermen get the products and prices they deserve.