A commercial fishing vessel captain steering in close quarters and fog conditions failed to reply to radio calls and danger signals from a tanker before the vessels collided Jan. 14, 2020 near Galveston, Texas, leading to the death of the captain and two of his crew, according to the National Transportation Safety Board.

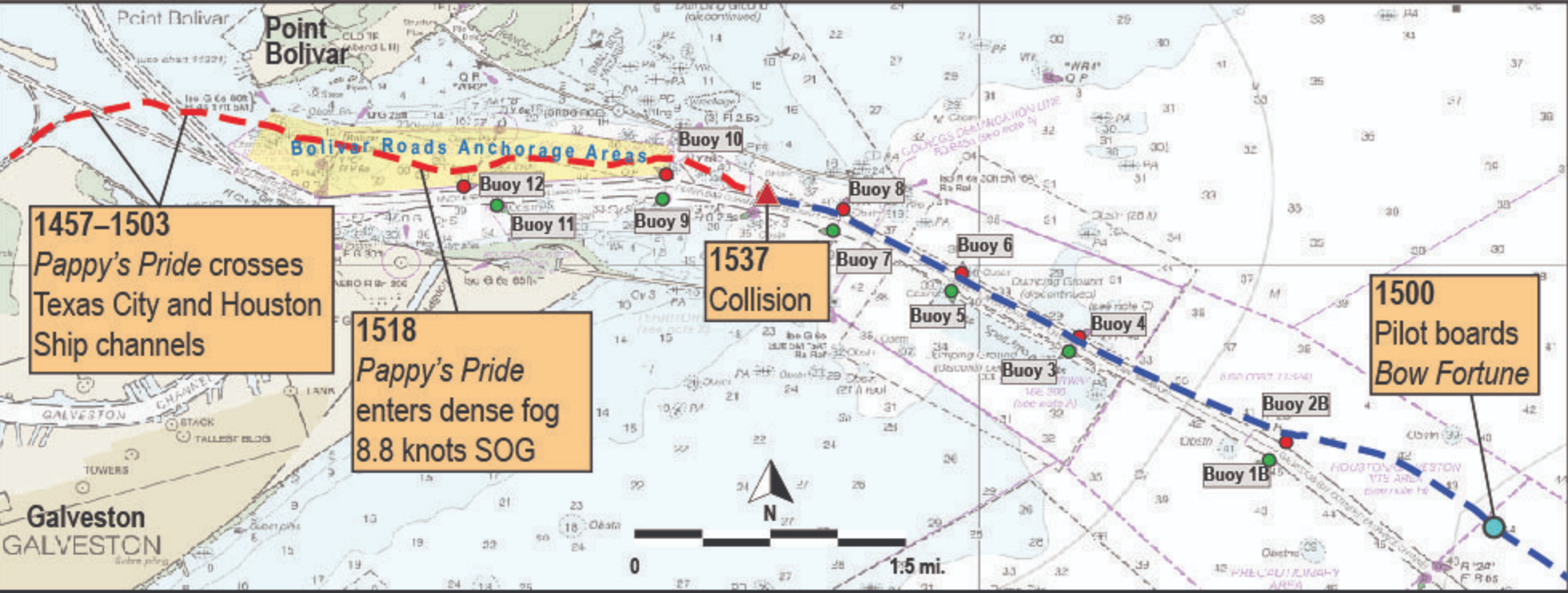

The 600-foot tanker Bow Fortune was transiting inbound in the Outer Bar Channel while the 87.1-foot Pappy’s Pride was transiting outbound, when the vessels collided in dense fog at 3:37 p.m. and the fishing vessel capsized and sank.

“Prior to the collision, the pilot of the Bow Fortune used VHF radio to hail the Pappy’s Pride three times and the Bow Fortune sounded two danger signals,” according to an accident report synopsis issued Thursday by the NTSB.

“The Pappy’s Pride’s captain had radar, automatic radar plotting aid and electronic charts onboard capable of showing the automatic identification system (AIS) information of nearby vessels,” according to the board. “The Pappy’s Pride AIS history showed that the captain made multiple course changes, indicating he was actively steering; however, the Pappy’s Pride did not reply to any of the radio calls or danger signals.”

Around 3:30 p.m. the Bow Fortune was at full ahead in the channel to counteract the effect of currents, the local pilot told investigators. Meanwhile the Pappy’s Pride was steering a course toward the channel and was about 0.14 miles or 246 yards to the north.

“The Bow Fortune pilot stated that he noticed the Pappy’s Pride on his PPU (portable pilot unit}at that point, ‘showing he was coming towards the channel.’ At 1535, the Bow Fortune pilot hailed the Pappy’s Pride twice,” according to the report.

“Although the Pappy’s Pride did not respond, electronic data shows that, shortly after the first attempted hail, the fishing vessel came 19° to port. The new heading, just north and slightly parallel to the outskirts of the channel boundary, put the Pappy’s Pride predicted vector as continuing to enter the channel at a very shallow angle and crossing ahead of the inbound Bow Fortune.

“About 1536, the Bow Fortune pilot sounded five short blasts, and the electronic data shows the Pappy’s Pride maintained its heading.”

On the fishing boat, the surviving deckhand could hear many vessels sounding fog signals but did not hear the Pappy’s Pride sound any. A first whistle signal from the Bow Fortune surprised the deckhands, and one told the other men he would “see what’s going on in the wheelhouse,” the survivor told investigators.

With a second and louder whistle signal, the survivor looked up and saw “this ship coming out of the fog.”

The Pappy’s Pride’s engine never changed speed “when entering the fog, during the transit through the fog, nor during the events leading up to the accident,” according to the crewman, who also stated that the fishing vessel didn’t turn at all before the collision.

With the collision the Pappy’s Pride capsized, and the Bow Fortune pilot hailed Vessel Traffic System and issued a mayday signal.

Within about 15 minutes the polit boat Yellow Rose rescued the survivor; a second deckhand was recovered unresponsive by a Coast Guard crew and pronounced dead at 5:05 p.m. Search and rescue efforts were suspended Jan. 16.

The Pappy’s Pride was raised Jan. 30, and the bodies of her captain and last crewman recovered from the wheelhouse. The Pappy’s Pride was declared a total loss estimated at $575,000. Damage to the Bow Fortune was negligible.

The report notes the Pappy’s Pride captain, 56, “had worked as a shrimp boat fisherman his entire adult life, and was a captain when hired by the company. He worked for the company for 7 years as the captain of the Pappy’s Pride homeported in Galveston, making six to eight voyages per year.

“Three weeks before the accident, he had been admitted to a hospital for a minor stroke. He was discharged after 3 days, when his symptoms improved. Medical testing did not determine the source of the stroke.”

Four days before, marine technicians had checked the Pappy’s Pride wheelhouse electronics. The autopilot was found satisfactory, but two of three VHF antennas and one of three VHF radios were faulty, according to the report, and technicians connected the good antenna to one of the good radios. Repairs were planned for when the vessel was in Mobile, Ala.

“The Pappy’s Pride was required to have two VHF radios when transiting a VTS area (to independently monitor the bridge-to-bridge and VTS-designated frequencies) and was required to respond if hailed,” the report stated. “On the day of the accident, the vessel transited the VTS area with one operational VHF radio/antenna combination. The VHF radio on the Pappy’s Pride had dual watch capability and was able to scan both channels at the same time.”

“Investigators determined the probable cause of the collision was the captain of the Pappy’s Pride’s outbound course toward the ship channel, which created a close quarters situation in restricted visibility. Contributing to the collision was the lack of communication from the captain of the Pappy’s Pride,” the NTSB concluded.

“Early communication can be an effective measure in averting close quarters situations,” the report said. “The use of VHF radio can help to dispel assumptions and provide operators with the information needed to better assess each vessel’s intentions.”