Like many Alaska fishermen, Luke Williams, 41, has known setbacks and faced financial hurdles. But Williams is determined not to let anything stop him from enjoying his life of working on the water.

Blown engines. Missed seasons. Bad prices. No fish. The resourceful Williams has not only survived but flourished in a game of adaptation — anything to keep him participating in the fisheries he loves. He’s worked long hours boxing groceries at local stores, borrowed start-up money from friends, purchased old boats by pilfering from his 401k and did his share of couch surfing with parents and friends when fishing turned tough in his younger years.

But he always springs back. “It’s just the fishing,” he says. “It’s all that I’ve ever wanted to do, just catch fish.”

Williams began his life on the saltwater, near Haines, Alaska, from the time he could walk, fishing with his dad and mom aboard an old wooden gillnetter, the Sockeye King. Among his earliest memories, he came to know pleasure and peril — thanks to Misty, the family cat that took up residence on the boat during salmon seasons.

As Williams describes it, the family was hauling in a gill net when curiosity beckoned Misty. The cat left the security of the galley, venturing to the top of the bulwarks where she could lean over to get a better whiff of the sea. Sure enough, Misty fell overboard with a splash loud enough to be heard over the clattering of the old chain-driven gill net reel. All heads pivoted from the well deck, a scramble ensued, and his dad saved the bedraggled feline from the water with a long-handled dip net.

Like that calico cat, the salty scent of Lynn Canal in southeast Alaska lures Williams to the precarious edge of financial stability. The prospects of catching salmon and Dungeness crab have thus far kept him from dry-docking his boats and committing to another career.

It’s not that he lacks the chops to make it in an array of occupations around town. He worked his way from box boy up to meat department manager at the local store (hence, the 401k). He’s built housing complexes in tribal construction gigs. Most recently he’s

augmented his fishing season by managing an environmental program with the Chilkoot Indian Association.

“If the weather is crappy I just go to my office job,” he says. “And if it’s nice I go run my 75 Dungeness pots.”

On office days, Williams still runs through his strings of crab pots in the evenings after his 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. workday. Even with the long daylight hours of the summer Dungy season, (mid-June to August) that would make for long nights if not for another innovation — a crazy-fast 19-foot skiff that gets him to his gear in a matter of minutes instead of hours, unlike slower boats he’s owned.

He debuted in his Dungeness operation several years ago with the Gee Whiz, a 29-foot fiberglass gillnetter he’d refurbished for a salmon fishing venture. The boat proved too slow and too costly. So he opted in 2017 to buy an old skiff from his dad, chop off everything above the hull, construct a lightweight deck and cabin, add hydraulics, and power it with a big outboard.

“It doesn’t cost me anything to run,” he says. “I spend maybe $30 or $40 to run my string of pots.”

To inquire about the renovation of the skiff and other boat projects invites yet another aspect of Williams’ life. He talks about cutting, gutting, fiberglassing, repowering, wiring, and plumbing hydraulic systems on boats with a passion on par with his experiences in the fisheries.

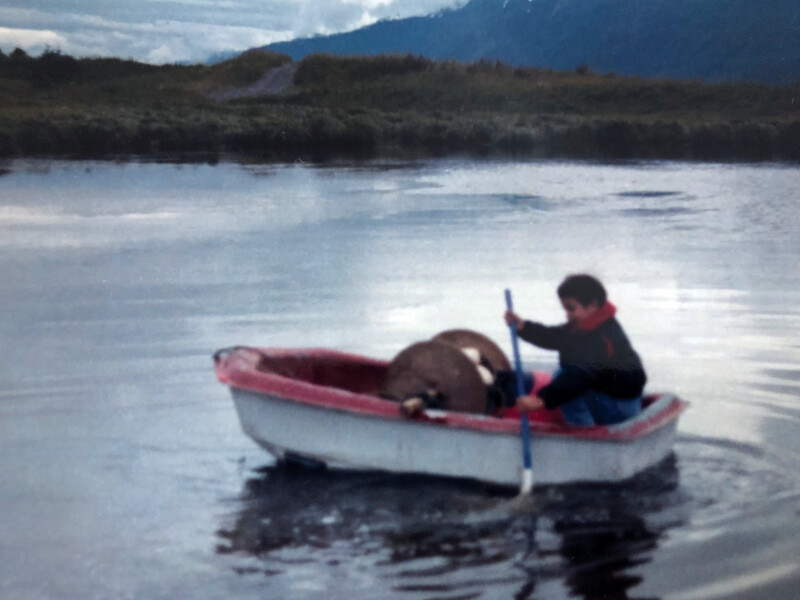

If you press him to choose which he favors, he’ll answer fishing over boat work, but as the stories unfold, and childhood photos attest, the two are inextricably entwined.

Like the time he resigned from a good-paying job, raided his retirement fund, and bought the Gee Whiz for the impending salmon season.

“I was excited, but nervous at the same time,” Williams recalls. “Here I was, going from a steady paycheck to fishing, where I didn’t know what my paycheck was going to be. But at that point, I knew that I was going to at least make something.”

He acquired the old boat, replete with its long-dead Chevy 454 gas engine, arranged a lease deal on a salmon permit, borrowed money from a friend, and ordered new gill net webbing out of Seattle.

Removing the rust-encrusted 454 from the bilges of the Gee Whiz was the easy part. Finding a replacement engine, making mounts, fitting the reduction gear, and aligning the shaft would cost opener after opener in the first three weeks of the gillnet season for chum salmon. Part of the conundrum was that the engine going into the boat turned out to be vastly different from the one that had come out.

Word of mouth around Haines had led Williams to the discovery of a tiny diesel engine. “We found a 62-horse Westerbeke diesel motor,” he says, “the kind that goes putt-putt-putt on sailboats. We stuck that in there. Then we had to find a reduction gear.”

Williams’ choice to use the mothballed motor was predicated upon his preference of diesel power over gas. That, and the unfathomable time and cost of getting a fresh 454 engine shipped from Seattle solidified his decision.

“I managed to score the motor for $300,” he says. “It was in an old boat, but it had only 100 hours on it.”

The first of the headscratchers came when Williams and his fishing partner lowered the baby Westerbeke into the expansive chasm that had accommodated the massive Chevy. Williams describes it like placing a peanut in a space that had been reserved for an elephant. That called for creative engine mounting.

“We tried making some of the mounting system out of old hardwood, but it just didn’t hold up,” says Williams. He ended up hiring a local welder, who scabbed a mounting system together from old scrap metal.

Then Williams had to align the shaft and cut a hole through the side of the hull for the wet exhaust. By the time the Gee Whiz splashed into the water, the better half of the chum season was shot.

There was, however, a late run of sockeyes. The boat worked flawlessly through the rest of a season that included one set yielding a pick of 7,000 pounds.

“I could tell we had a good load in the hold,” Williams remembers. “The boat sat low enough in the water that the wet exhaust pipe was blowing bubbles.”

Though Williams went on to catch more sockeyes that summer, his earnings came in skimpier than he had hoped. He paid off his bills for fuel, the permit lease, a crew share to his deckhand, and other expenses.

“After it was all done I didn’t have a lot of money left to put in my pocket,” he says.

Undeterred, Williams bought a Dungeness permit in 2017 which enables him to run 75 pots with his dad’s old refurbished skiff.

Since then, he’s seen the thick and thin of profitability. In 2020 his crab season coincided with the onslaught of Covid. The abundance of crab that year set records, but the infrastructure was missing to get the crabs processed and to market. Last year, the infrastructure returned, but appreciable volumes of crab did not.

In the grand scope of Williams’ attitude toward fishing, that was then and now is now.

This April, Williams entered the loan application process in hopes of buying a salmon permit. He hopes to launch in May his newest endeavor, a 32-foot 1979 fiberglass gillnetter named the Enterprise. Williams had purchased the boat in 2015 but finances delayed his plans to rebuild it for the 2019 season. Further delays ensued with covid slowing down deliveries of needed supplies to finish the project. Since then, back-ordered shipments of hydraulic hoses, wiring, and parts for the 3208 Caterpillar and rigging have finally arrived.

“It’s all there,” says Williams of the ingredients to his next fishing venture. “All I have to do is put it together, throw it in the water and go.”