A recent informal survey on FaceBook asked fishermen what gear they would never go offshore without. Many responded that they’d never leave port without a survival suit. “That’s smart,” says John Roberts, director of safety training at Fishing Partnership Support Services, a Massachusetts-based non-profit dedicated to improving the health, safety, and economic security of commercial fishermen. “A survival suit is probably the most important piece of safety gear you can have on the boat.”

After 30 years doing search and rescue for the U.S. Coast Guard, Roberts joined the Massachusetts-based Fishing Partnership two years ago and has been running safety trainings for fishermen around New England. “We teach them how to don and doff the suit, that is, get in and out of it, and how to get in the water,” says Roberts. “We encourage them to bring their own suits, and we go over how to store and maintain them,” Roberts notes that zippers should be waxed and lights in working order. “The reflective tape shouldn’t be peeling off. Sometimes a guy might have bought a suit and not used it, and we unpack it, and it’s got dry rot, or the zipper is rusted.”

The Coast Guard has a table—based on length, registration, and distance from shore—that indicates which vessels are required to carry survival suits for the crew, but Roberts recommends having your own suit, even if the vessel is not required to have one for you. He adds that certain vessels are required to conduct safety drills once a month, and those need to be conducted by a certified drill instructor. He also notes that the survival suits should be serviced every two years. “They blow them up with air and look for leaks, dry rot, and open seams, and make sure everything is working.”

When it comes to brands, Roberts can’t make recommendations. “When you look around, Kent and Imperial seem to be the most popular brands, but Guy Cotton is making suits [Piel brand], and Viking is still making them, and Mustang. The important thing is not the brand, it’s that you have it with you and that it’s in good working order.”

USCG safety inspector Kyra Dwyer conducts survival suit training for fishermen in southern New England and has a few things she likes to focus on. “I think having the right size suit is important,” Dwyer says. “And being familiar and comfortable with it, learning how to get in the water and stay face up.” Dwyer has been working with fishermen for a long time and helps them understand what can go wrong. “I teach them to pull the suit up to their waist and then tighten the ankle straps so that air doesn’t get into their feet and invert them. The Imperial model has two toggles for pulling the zipper up: one on the zipper and a stationary one to pull down on and create tension. Sometimes people will grab the stationary one and pull and it doesn’t move, and they panic.” On a practical level, Dwyer also prioritizes accessibility. “You have to bale to get to it, sometimes in the dark,” she says.

Mind control is also a vital part of survival, Dwyer notes. “When I’m doing training, I always ask if anyone has been in a real-life situation,” she says. “And there’s always somebody, and they all say that calming your mind is the hardest part. That is why I focus a lot of the training on mindset. Getting people to understand that their survival suit is now their shelter, and it’s a pretty good one.” Dwyer points out that psychology is as important as the mechanics of getting in a suit and staying face-up in the water. “I want people to realize that they have a pretty good shot at making it.”

Adding to those chances, many survival suits now accommodate a Personal Locator Beacon PLB. “They’re not required, but they are great, “ says Dwyer. “Most PLBs have to go to a satellite and then to land, but ACR electronics are now making them with AIS so vessels nearby will see you on their plotters immediately. I like that.”

The ACR ResQLink AIS PLB also includes Return Link Service (RLS) technology. “It flashes a blue light when your message is received,” says John Roberts of Fishing Partnership.

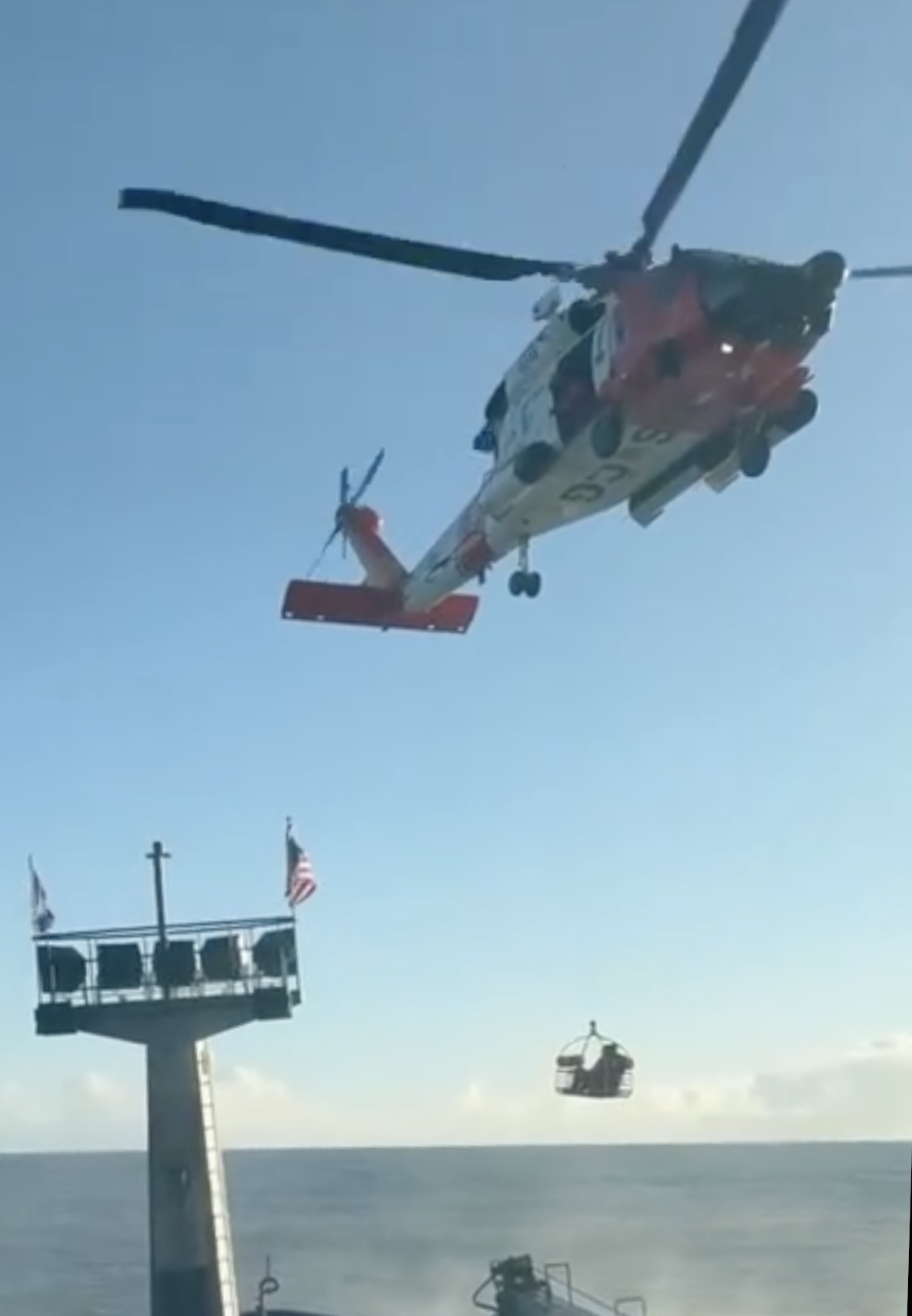

Besides survival suits, Dwyer and Roberts also conduct life raft training sessions. After 31 years in the Coast Guard in Alaska and elsewhere, Roberts has found a few empty rafts and debris fields, and many miracles. “When I was new, another vessel rescued these guys from a clammer that capsized off Maryland. They were hypothermic, and they were down forward having hot coffee and whiskey. I came aboard to check on them and said, ‘You shouldn’t have that.’ These grizzled old guys just looked at me.”

Robert’s raft training includes how to get into a raft, how to right it if it deploys upside down, and how to check that everything is in order in the raft. “I like to have them there when the raft deploys and then we go through everything, the drogue, the Solas pack with food and water and a bunch of other things.”

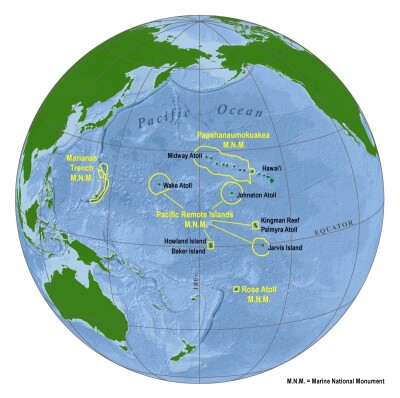

The Solas packs come in two versions: B and the more comprehensive A, which includes food rations and a fishing kit. The total contents can be seen here. “What type of raft you need is determined by a number of criteria,” says Dwyer. “It depends on where your fishing, vessel length, average water temperature, and some other things.”

When Dwyer conducts trainings, she focuses on the mounting of the raft and the functioning of the hydrostatic release. “You don’t want your raft under a radar or anything like that,” she says. “Anything that can snag it. And you want to make very sure that the hydrostatic release is put on correctly and in good working order.” Dwyer notes that the hydrostatic release may be a fisherman’s last hope when a vessel goes down quickly. “It’s breathtaking how fast things can go wrong,” she says.

I’m writing this story with the news that two fishermen, a father and son from where I live, were lost in a 34-foot boat while trying to get around West Quoddy Head and plow through 9-foot seas. No Mayday—something happened fast. They were just under the 36-foot requirement for having a life raft.

Captain Terry Hayward of Broad Cove, Nova Scotia, faired better when the 138-foot Cape Dorset, a freezer trawler he was running, went down on the Grand Banks on February 22, 2014. “A weld broke aft,” says Hayward. “The engineer called me and told me he had we were very lucky, 12 hours earlier it was nasty. 75 to 80 knots from the WNW and 12+ meter seas, I made the call to abandon ship at 09:15 hrs. 19 crew onboard, all came home safely.”

The four twenty-man inflatable life rafts, 2 per side, on the Cape Dorset, gave the survivors some comfort while they waited for rescue.

Dwyer notes that raft size can be an issue. “A lot of these rafts say 6-man, but you put six men in there and it can feel a little crowded. So, I tell people to look closely at the actual size.” Dwyer also recommends that fishermen observe their rafts being serviced. “They can get familiar with it that way,” she says.

Greg Sholly of the Maine company, Survival at Sea, notes that Survitec and Revere are the main brands he sells to commercial fishermen. “There’s a Coast Guard checklist they can log into online; they enter the information about their boat, and it tells them what they need for a raft,” Sholly says. “They’re required to have them serviced annually, and we guarantee a three-week turnaround. Right now, we’re at one and a half weeks.” Servicing a raft is an 8-hour job, according to Sholly, and it involves checking the CO2 canister to make sure it’s full and checking the Solas pack in case anything has expired or gone bad, among other things. “We also inflate the raft to make sure it’s not leaking and check that all the glued-on features are secure. We check the pressure relief valve because if a raft gets deployed in 70-degree water, it can overinflate. In cold water, it might need more air.”

To add to security, Sholly is required to notify the Coast Guard about every raft he services. “They audit us,” he says. “Fortunately, none of our rafts have ever failed.”

While most fishermen hope to never end up in a survival suit or raft, it’s good to be prepared. “When the Three Girls sank 100 miles of Portsmouth, NH last summer, the crew had just done a training and they got off safe,” says Roberts. “We have a calendar of our trainings online.”