Cooperative surveys by scientists and fishermen have laid groundwork for the first baseline study of how offshore wind turbine construction will affect southern New England fisheries, and organizers are seeking more advice for fine-tuning the effort and reviewing its findings.

“We’re really designing this on the fly,” said Steve Cadrin, a professor at the University of Massachusetts School for Marine Science and Technology, referring to the review process, during a virtual meeting Thursday with fishermen and scientist advisors. “We’re wide open on how we can do this better.”

With offshore wind development plans surging ahead under the Biden administration, there’s a scramble in the marine sciences to understand how the potential construction of hundreds of turbines off the U.S. East Coast could change regional ocean environments and fisheries.

“Getting a baseline (study) is a real challenge” given the speed of recent developments, and the UMass-Vineyard Wind project is drawing on decades of fisheries survey work in Northeast waters, said Cadrin.

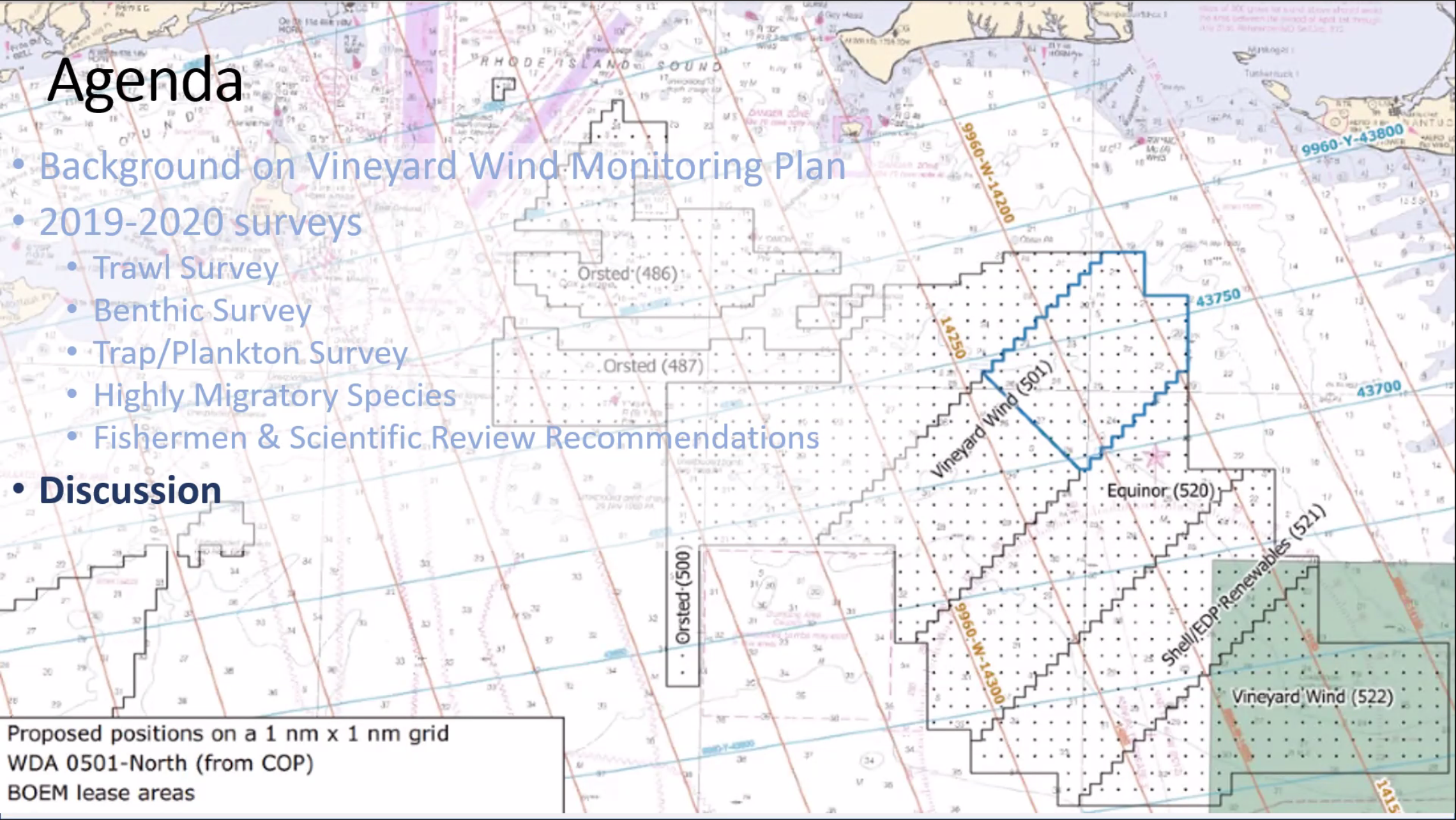

Based on eight surveys since 2019, researchers have determined that protocols used in the Northeast Area Monitoring and Assessment Program (NEAMAP), an integrated, cooperative state and federal data collection program, will be sensitive enough to “detect a moderate change for most important commercial species” such as whiting, longfin squid and summer flounder when the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project is constructed, said Cadrin.

The NEAMAP methodology calls for pulling survey trawl nets for one tow every 30 square miles of ocean, to collect data on a finer scale than the 100 square mile grid of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration annual surveys.

In addition to the trawl survey, the UMass program is using drop cameras to assess life on the sea floor; fish traps to count lobster and black sea bass; and collecting information about recreational fishing for highly migratory species like tuna and marlins, a big business for the southern New England charter fishing fleet.

“Each survey was designed in collaboration with fishermen” who added their local and regional knowledge to that of scientific advisors, said Cadrin. “They’re highliners in these species.”

Fred Mattera, executive director of the Commercial Fisheries Center of Rhode Island, said virtual meetings should be a regular feature of the study to bring in more insights.

“This is the first one (offshore wind fisheries study) out of the gate,” said Mattera. He asked if the UMass and NEAMAP methodology could serve as a standardized design for fisheries studies around other wind projects.

“That’s what we recommend,” Cadrin replied. Rutgers University is planning to use the NEAMAP trawl protocol for its study of Ørsted’s Ocean Wind project off New Jersey, “so I think the probability is very high,” he added.

Next door to the Ocean Wind lease area off New Jersey, Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind LLC announced Thursday that it and Rutgers are launching “a multi-phase modeling study in collaboration with the surf clam industry.”

“The goal of the study is to better understand how Mid-Atlantic wind farm developments that are anticipated over the next 30 years, along with climate change, may influence the distribution and abundance of surf clams,” according to a statement from the company. “The study will also examine the economics of the surf clam fishery within the Atlantic Shores lease area and the greater Mid-Atlantic Bight.”

The study is based on a Rutgers model called the Spatially explicit, Ecological, agent-based Fisheries and Economic Simulator that was developed in partnership with the surf clam industry, fisheries managers, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and National Marine Fisheries Service.

The simulator models the surf clam stock biology along with fishermen and fleet behavior, federal management decisions, fishery economics and port structure. The new project will add planned offshore wind energy development and operations over the coming 30 years to the mix.

“We are looking forward to having our model take this next step towards ‘future casting,’” said Daphne Munroe, the study’s principal investigator and associate professor of marine and coastal sciences at Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences. “The strength of our modeling approach lies in the information and advice we are generously provided by advisors, in particular the New Jersey surf clam fleet, who have a deep working knowledge of the systems we are trying to simulate.”

“We appreciate the willingness of the surf clam industry to actively participate with us in this effort,” said Jennifer Daniels, development director at Atlantic Shores. “This study is the latest in our continued commitment to lead with science by making our lease area available to researchers and mariners alike. It’s through the application of tools like this simulator that we can responsibly develop our lease area and deliver renewable energy for New Jersey communities with minimized effects on the fishing industry.”