On the chilly morning of May 18th in Trescott, Maine, Jay Dinsmore prepares for the start of the 26-day halibut season. Accompanied by his daughters, he gathers his fishing gear - halibut hooks and bait - and loads them into his truck. He then carefully backs up his truck, aligning it with the trailer carrying his skiff. Jay's primary goal is to fill his freezer with halibut for personal use, but he also sees this as an opportunity to occasionally earn some extra money.

“It used to be you could make some money at it,” Dinsmore says of the state’s halibut fishery. “But this year, they’re only paying $6 or $7 dollars a pound. You’d have to be getting at least $10 to do anything. I’m fishing because I like it. I’ll fill the freezer, sell some to folks around here, and give some to family members and friends. Plus, I like seeing my kids enjoying it.”

Dinsmore’s 23-year-old daughter Kayla is his crew, and today his 5-year-old daughter, Delilah, is going along for the ride. It’s 6:30 a.m., and calm when they reach Bailey’s Mistake, about 8 miles from the town of Lubec and the Canadian border. Delilah jumps into the skiff as her father prepares to launch it. “Hold on there, Peanut,” says her sister Kayla. “You’re not going anywhere without a life jacket.”

A quarter-mile off the beach, sheltered by a ledge, Dinsmore’s boat, the Carrie & Kayla, lays on her mooring. “It was a Dixon 45,” Dinsmore says as he and the girls shift bait and gear from the skiff to the big boat. “But I added 4 feet to the stern, so now it’s 49. It’s 16-foot 8 wide.” Powered by a 750-hp John Deere, the Carrie & Kayla rumbles to life. Dinsmore casts off the mooring and steers out of the mouth of Bailey’s. “Do you remember where we caught that halibut when we were dragging last winter?” he asks Kayla.

“No, I don’t,” she says as she baits circle hooks with alewives – showing her little sister how it’s done. Delilah, with a winter coat over her life jacket and adult-size gloves, manages to pick up a fish and hand it to her sister.

“I can’t remember either,” says Jay. “But that’d be a good place to start.”

About a mile offshore – it’s a state fishery and limited to three miles out – they make their first set in 235 feet of water. Kayla runs the boat while Jay tosses the first anchor off the stern. As the groundline sinks, he snaps on a baited hook about every fathom. Gulls hover, but the bait goes too deep too fast, and they can’t steal it. “I guess we’ll find out what’s out here,” Jay says as he runs out of groundline, and tosses the second anchor and buoy. “We’d probably get more if we could fish federal waters.”

Back in the wheelhouse, Jay watches his Garmin plotter, a GPSmap 4210. “I’m looking for inclines or declines,” he says. “Halibut have eyes on top of their heads, and they’re always looking up. You see this here? That looks like a rocky edge. We’ll try that.” Dinsmore spreads out his sets. It’s early in the season, and he’s prospecting. But he’s fished these waters for decades and has a pretty good idea of where to find fish.

He sets three more trawls but runs out of alewives halfway through the process. Kayla and Delilah have been trying to thaw out a box of frozen herring and mackerel, but it’s a slow process with the weather so cold. Kayla starts baiting with the half-frozen fish, and it’s not pretty. “I don’t think this is going to stay on too good,” she says, shaking her head as she pokes the point of a hook through a fish’s eye and then back through its spine. When the fish are small, she starts putting two on each hook.

Alewives are the bait of choice for halibut fishing, and this time of year, Maine’s rivers are full of them as they swim from the ocean to freshwater to spawn. “The way the law is you can only dip 25 alewives per person,” says Jay. “The towns auction off the right to harvest more. I got to find out who’s doing it over in East Machias.” But until Jay can get some more alewives, Kayla baits with the soft herring and mackerel.

With all the hooks in the water, about 50 per set, and four sets spread over a few miles, the crew heads back ashore for lunch. “We’ll head out again at about 3:30 and see what we got,” says Dinsmore.

When the crew arrives back on the boat in the late afternoon, with the addition of a neighbor, Jeremy McPhee, the wind has come on stronger and swung to the southwest. The sun shines bright as the occasional white cap flashes on the increasingly choppy sea.

Dinsmore heads out to the furthest set, a couple of miles off Moose Cove. Kayla gaffs the buoy and wraps the line around the hauler. Jay steps in and starts to wind the buoy line aboard. When he gets to the groundline, the hooks rise out of the water clean and empty. Kayla unsnaps them and passes them to Jeremy, who rebaits them with herring and mackerel. Everyone crowds the rail when Jay indicates a fish on. But it’s a cod, a big one, and lively. Illegal for this fishery, it goes back into the water.

The second haul back yields better. “Got something on,” says Jay. He mentions that he prefers to not to gaff fish that may be undersized, but when the halibut shows, everyone pressing the rail can see that it’s a big one. Jay slides the gaff back to Kayla and continues to pull the fish in by hand, not wanting to risk the hauler that could tear the hook out. “Get it through the head,” he says to Kayla.

She hooks the fish, and with help from McPhee they slide the fish in over the rail. Kayla jumps aft and cuts its tail to bleed it as her father continues to haul. Delilah peeks out from the wheelhouse, her eyes wide with fright at the site of the bloody halibut taking bites of air with its sharp teeth. “I don’t like that fish,” she says.

“Another one,” says Jay, but he shakes his head when he sees it, obviously below the limit. With the hooks aboard and baited he resets the gear as the wind picks up. “I thought it would die down when the tide turned,” he says. But the whitecaps flash more frequently, and little Delilah has to hang on to keep from flying around the wheelhouse.

On the third haul, they get a borderline fish. When Jay measures in on the rolling deck, he’s not happy. “Forty-one,” he says. “When it shrinks, it’ll lose an inch, and they’ll write us up for it.” Kayla looks at him, they’ve been working together for years, and he gets the message. “Okay, do what you want,” he says.

She measures the fish more carefully and comes up with 43 inches. “Okay,” says her father. “I just want to know it’s going to be over 41.”

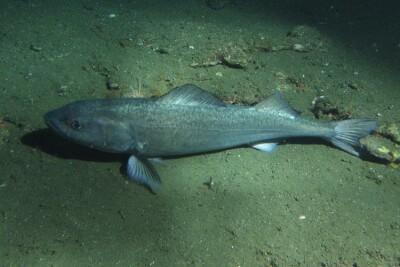

According to research done by U.S. and Canadian scientists, the Gulf of Maine halibut take anywhere from 7 to 12 years to reach sexual maturity – at around 39 inches. Historically, males can live for 50 years. “My brother caught one that was 236 pounds,” says Dinsmore. “One hundred fifteen pounds was the biggest I caught.”

By the time Kayla hooks the buoy for the last haul, the wind is whipping big bouquets of spray off the bow, and everyone braces against something to keep from falling. Jay starts hauling the buoy line up and is surprised to find his groundline coming up with it, and fish everywhere. He and Kayla look over the side at the mess, a big fish in the middle of it and smaller fish visible deeper down.

Wordlessly they gaff the big fish aboard and start sorting the tangle, cleating off the groundline, they start unsnapping hooks and shaking out the knots. They get the three small fish aboard and the last anchor. With everything in order, it’s like it never happened.

On the way back in, Jay measures and logs the small fish before McPhee slides them back into the water. Kayla guts the three keepers on deck. “Look, this one has a crab in it,” she says.

“Nothing eats more crabs than a halibut,” says Jay

As the boat gets into Bailey’s Mistake, the seas calm, and Kayla holds up the two smaller fish for a photo. Together they are close to a hundred pounds, and the big one at her feet might run 80 pounds – or so Jay guesses. Not a bad start for the season, but weather and the vagaries of fish behavior and abundance will determine how things pan out.

In 2022 landings for Maine halibut totaled 27,450, which falls in line with the 2000-2010 average of 29,000, but far below the 2016 record of over 100,000 pounds.

Each licensed commercial fisherman can buy 25 tags and land 25 halibut in the season. “Some years I limit out,” says Dinsmore. “Other years I give it up if I don’t catch anything for a few days in a row.”

For the price he’s seeing, Dinsmore doesn’t plan to go too hard, and halibut has never been a major factor in his business model – he relies more on lobstering, dragging scallops, and other work. For the Dinsmores, halibut fishing is more about family, food, and fun.