A federal judge granted the National Marine Fisheries Service a May 31, 2021 deadline to produce new biological opinion on the Northeast lobster fishery and northern right whale, following up on his earlier ruling that the agency had violated the Endangered Species Act with a 2014 opinion.

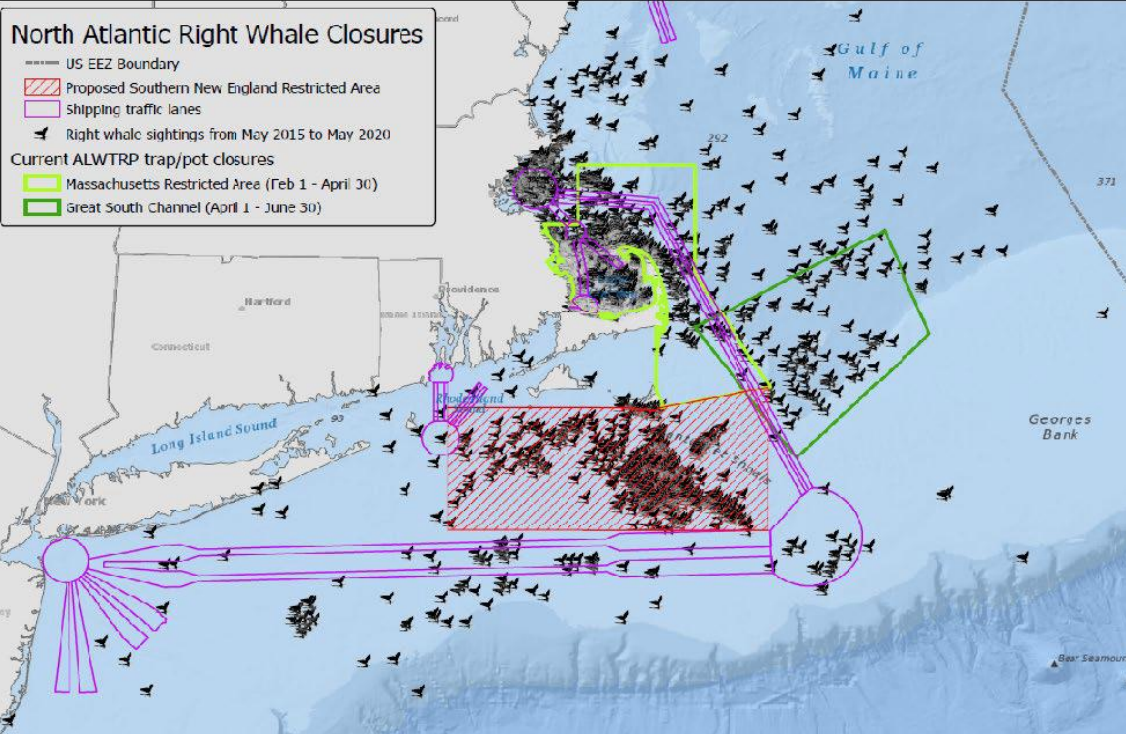

Boasberg also decided against ordering an immediate halt to the use of vertical lines for lobster gear in an area traversed by right whales south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket – a ‘Southern New England Restricted Area,’ about the size of Connecticut, proposed by plaintiffs including the Center for Biological Diversity and Conservation Law Foundation.

In a 31-page memorandum of opinion, the District of Columbia judge laid out his reasoning, and recognized the difficulties NMFS faces in resolving the right whale issues. But he included a stern warning to the agency and to make progress.

“Although the Court therefore finds the May 31, 2021, deadline acceptable, it will look with considerable disfavor on any future requests by NMFS for even more time to complete the new rule and BiOp (biological opinion),” Boasberg wrote. “Delay, it seems, has been a primary strategy for many TRP (take reduction plan) stakeholders, and NMFS effectively tolerated such tactics despite previously representing to the Court that it expected to have a proposed rule and draft BiOp complete more than a year ago.”

“The good news is that all stakeholders in the lobster fishery, including conservation groups, are not starting from square one,” Boasberg noted, outlining longtime efforts to reduce lobster gear interactions with northern Atlantic right whales, now numbering only around 400 animals.

The environmental groups won their essential point when Boasberg ruled April 9 that NMFS’ 2014 biological opinion stating that the American lobster fishery “may adversely affect, but is not likely to jeopardize, the continued existence of North Atlantic right whales” failed a critical responsibility.

The judge ruled then against NMFS and in favor of the plaintiffs’ argument, noting that the agency failed to include an “incidental take statement.” That failure, the judge declared, rendered the biological opinion illegal under the Endangered Species Act.

The environmental groups cited previous delay in calling for a Jan. 31 deadline for a new biological opinion, and imposing the southern New England closed area as an immediate protection for whales. In that scenario, without a new opinion ready by Jan. 31, NMFS could have been be forced to close the lobster fishery Feb. 1, the judge noted.

Among other considerations, the judge decided giving the agency another four months to complete its new opinion and rule would be reasonable.

In court NMFS has said “the risk of entanglement of right whales in NMFS-controlled waters between January and May 2021 is not pronounced enough to warrant “emergency . . . action in an expedited timeframe with limited public involvement,” largely because lobster fishing decreases during those cold months,” the judge wrote.

In deciding against imposing a southern New England gear closure, Boasberg in his memorandum discusses a range of potential effects brought up by all parties to the lawsuit, including the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association and other industry advocates who joined to help NMFS defend its actions.

Lobstermen’s withdrawal of gear during the winter is one factor, but the judge also cited the danger of unintended consequences cited by industry advocates – including a warning that closing such a large area would lead to more gear being concentrated in other areas, potentially leading to entanglements if whales swam over more crowded fishing grounds.

Despite falling short on their goals of an earlier deadline and closed area, the environmental groups say Boasberg’s opinion now sets out a clear timeline.

“The judge has given the agency clear marching orders, and there’s no more time to waste. The National Marine Fisheries Service must respond quickly with strong new regulations that prevent right whale entanglements,” said Kristen Monsell, a lawyer with the Center for Biological Diversity attorney who argued the case in court.