Maine lobster fishermen have won an emergency reprieve in federal court from a planned Oct. 18 seasonal closure that NMFS regulators say is needed to save endangered northern right whales.

In a ruling issued Saturday, U.S. District Court Judge Lance Walker granted the Maine Lobstermen’s Union application for emergency relief from the closure, affecting Gulf of Maine waters from offshore Casco Bay to Mount Desert Island until January 2022.

“This victory by the Maine Lobstering Union is a significant step in protecting one of Maine’s most precious industries – lobstering,” said Alfred Frawley, the attorney who represented the Maine Lobstering Union, which has about 200 members.

“The lobstering industry is not only a treasure to Maine but a treasure to our American history. The regulations proposed by federal agencies would have had a chilling impact on communities throughout Maine. We will continue to push for science and data that reflect what is truly happening in our industry.”

Along with the union, plaintiffs in the case are the Fox Island Lobster Company of Vinalhaven and owners Frank Thompson, a sixth-generation fisherman and his wife Jean; and the Damon Family Lobster Company of Stonington. The lawsuit was brought by the Portland law firm of McCloskey, Mina, Cunniff & Frawley, LLC

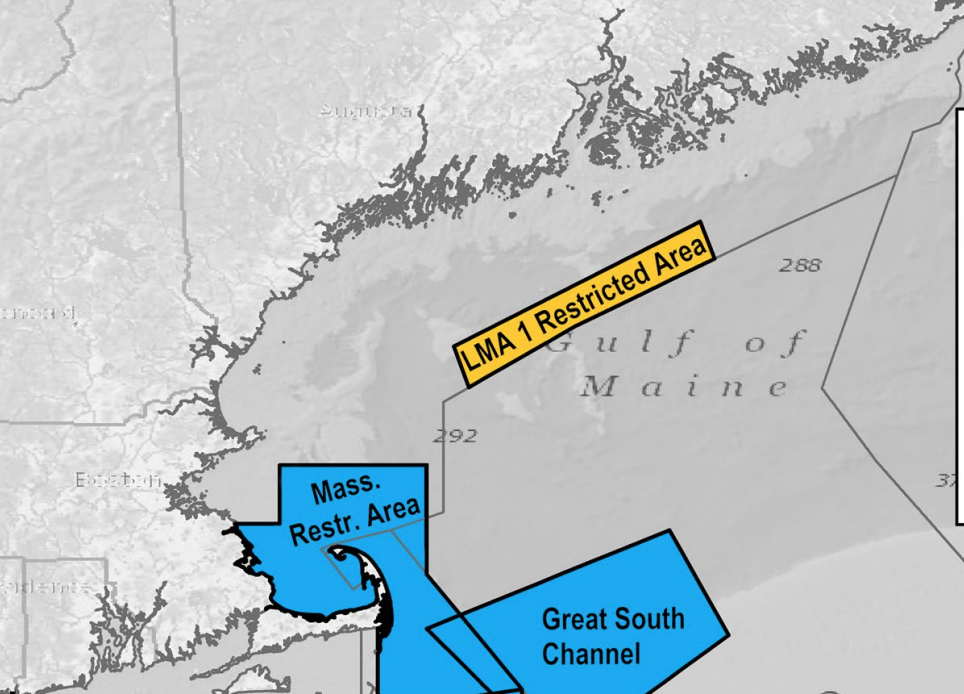

Walker in his 28-page decision expressed skepticism that NMFS’ statistical modeling of whale movements and lobster fishing areas is sufficient to justify closing 950 square mile of ocean – referred to as LMA 1 in the agency's latest plan to reduce the danger of entanglement is fishing gear.

The agency used a decision support tool (DST) designed by the Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

“NMFS has turned to the DST to substantiate a closure in LMA 1 because NMFS understands that trends over the last decade have made the Gulf of Maine less appealing to right whales,” Walker wrote. “Moreover, NMFS lacks any traditional evidence that Maine fishing gear has been responsible for the take of a right whale in recent years.”

The judge outlined how the DST “aids in the comparison of spatial management measures by calculating right whale entanglement risk based on three components: the density of lines in the water, the distribution of whales, and a gear threat model to determine the relative threat of gear based on gear strength.

“Thus, while NMFS purports to base seasonal closures on a co-occurrence of whales and line densities, the question is whether the DST substantiates the LMA 1 closure based on meaningful migratory data or simply uses math in a manner that makes a reduction in line density appear statistically meaningful even in the absence of passing whales.”

If NMFS’ modeling was the only evidence available to support the new whale preservation efforts it could be justified, the judge wrote.

“But that is not the case – the agency does have the ability to generate evidence more reliable than abstract mathematical models to prove or disprove right whale occurrence rates in the Gulf of Maine in the winter season, most notably in the form of passive acoustic recorders that have this year been placed along the Maine coast and could have been placed earlier during the multi-year review process that resulted in the Final Rule,” the judge added.

Walker said the lobstermen’s challenge meets the burden of showing “irreparable harm” to their fishery, justifying a preliminary injunction to forestall the area closure. Much of that cost would fall on the island communities of Vinalhaven and Stonington, the judge noted.

Walker added their concern is not just losing access to the lobster grounds from October to January, but the potential of losing them “to larger economic forces with which they compete.”

Those could include mobile gear fishermen who have been unable to access the area because of lobster trawls – and potentially new lobster fishermen using ropeless gear who could fish during area closures. NMFS says the closures are one more incentive to develop reliable pop-up buoys and vertical lines.