A Coast Guard study that recommends against designated vessel transit lanes through New England offshore wind turbine arrays “contains serious foundational and analytical errors that merit correction,” commercial fishing advocates say in a formal objection to the findings.

The Coast Guard’s Massachusetts and Rhode Island Port Access Route Study endorsed wind power developers’ proposal for a uniform grid layout of 1 nautical mile between turbine towers on their neighboring federal leases off southern New England.

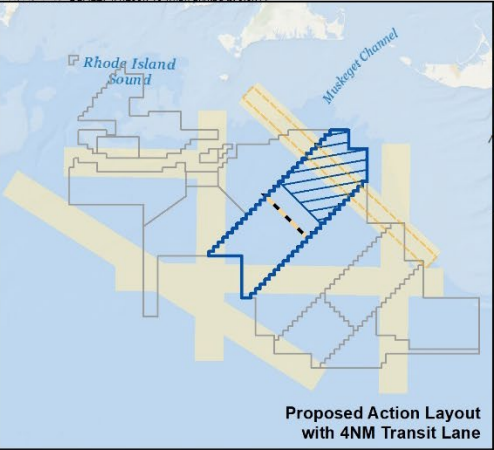

The report found fault with a proposal for up to six vessel transit lanes, up to four nautical miles wide, that was proposed by the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a coalition of fishing industry groups.

Developers of Vineyard Wind, the first 800-megawatt project to start construction in the region, and their supporters stressed the Coast Guard’s support for a uniform grid layout as the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management commenced public hearings on its environmental review of the plan.

“We are grateful that the USCG included the transit proposal submitted by RODA, and developed for years prior by multiple entities, in the Federal Register materials. However, the information disseminated in the Final Study does not evidence a basis of objective data and analysis,” wrote Annie Hawkins, RODA’s executive director, in submitting the objection along with RODA staffers Fiona Hogan and Lane Johnston.

“We do not purport to question the USCG’s deep knowledge and professionalism regarding maritime safety but echo the concerns of thousands of fishermen and fisheries experts that the (port access study) conclusions remain wholly unsupported and unsubstantiated by its associated record.”

The detailed 14-page “request for correction” calls for a peer review of the Coast Guard study and cites what it calls mistakes in calculations and how the Coast Guard gathered information.

Correcting them is imperative, the letter states, because the Coast Guard findings are now informing and influencing the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s supplemental environmental impact statement for the Vineyard Wind project, and larger assessment of East Coast impacts.

“Repeatedly throughout the SEIS, BOEM cites the draft (port access study) finding that “the 2020 draft Massachusetts and Rhode Island Port Access Route Study provided quantitatively derived recommendations for turbine spacing and transit lane widths within the wind arrays,” the RODA document states.

“BOEM then goes on to state: ‘As a cooperating agency with BOEM, BOEM and USCG will continue to consult over the course of the NEPA process for the proposed Project as it relates to navigational safety and other aspects, including the impacts associated with alternatives assessed.

“In short, BOEM is basing its understanding of the impacts of the alternatives, and thus its regulatory decision, on the information provided” by the Coast Guard report, the request says.

Among other shortcomings, the Coast Guard analysis relied heavily on Automatic Identification System (AIS) vessel tracks to assess maritime traffic around the Vineyard Wind site – despite cautions from the fishing industry and other sources that commercial fishing vessels rarely use AIS, the RODA paper says.

A list of nearly 900 contacts included as stakeholders in gathering information for the study “includes numerous recreational fishermen, municipal and state authorities, environmental advocacy groups, offshore wind developers, ferry companies, reporters, and even police departments. Only three commercial fisheries contacts are included; one of which is not an active fisherman but a Fisheries Liaison officer for one of the wind developers,” according to RODA.

“Including only two active fishing contacts in the formal outreach plan is not sufficient to inform a study primarily focused on fishing vessels,” the request notes.

In endorsing developers’ proposed 1-nautical mile grid layout for the southern New England turbine arrays, the Coast Guard study “purports to characterize appropriate turbine layouts to maintain fishing activity within the WEA (wind energy area) but there is no information whatsoever as to vessels’ spatial requirements or other important factors when engaging in fishing (i.e. when gear is deployed and hauled).”

Yet the report “boldly asserts that ‘the recommended standard and uniform grid pattern provide sufficient space for certain vessels that fish in the WEA to continue fishing after the wind farms are constructed,’ with absolutely no supportive evidence, and then goes even further by concluding that should larger transit corridors be adopted, ‘the reduced turbine spacing would largely preclude fishing in the WEA.’”