The Biden administration could reinstate commercial fishing restrictions on the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Monument – and bring a new court challenge from the fishing industry, just months after Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts indicated he would be open to hearing a new case.

Reports Monday in the Washington Post and New York Times described a recommendation from Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to restore boundaries of the Bear Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in Utah, which were established by former presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, and cut back by former president Donald Trump in December 2017.

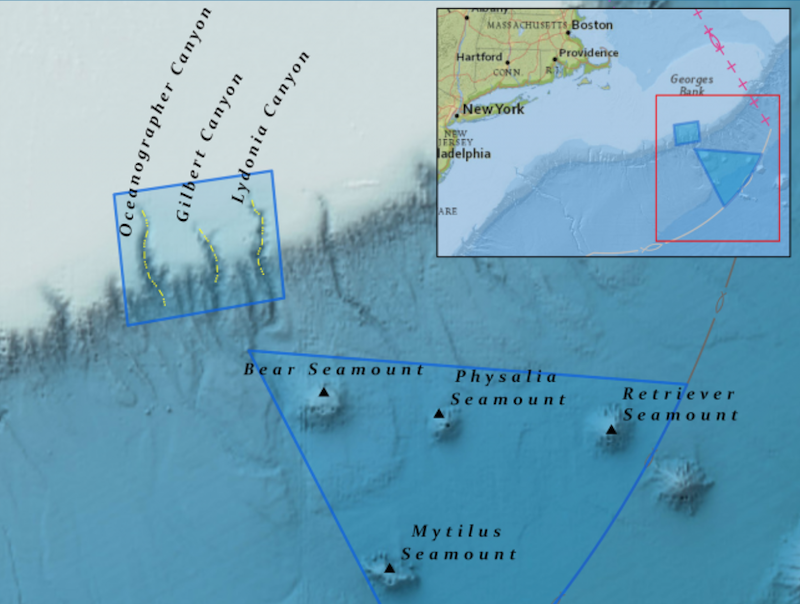

At the urging of ocean environmental groups, Obama imposed commercial fishing restrictions after establishing the 5,000-square mile Northeast marine monument in December 2018. In June 2020, Trump issued a new proclamation lifting those rules.

Within hours of President Biden’s inauguration Jan. 20, environmental groups pressed him to reimpose fishing restrictions, and fishing advocates mobilized, hoping to head that off.

How Biden decides this could set the stage for a new challenge to presidential authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906, which critics say has expanded far beyond its original intent.

“A commercial fishing ban serves no conservation benefit,” said James Budi of the American Sword and Tuna Harvesters, which has urged the Biden administration to hold off on renewing restrictions.

Officials at NMFS themselves say “pelagic longline gear used to catch swordfish has no impact on habitat,” said Budi. “Fishing impact on the monument below us is like a bird flying over the Grand Canyon.”

Federal district and appeals courts upheld the Obama monument designation against a challenge from the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association and allied industry groups. On March 22 the Supreme Court declined the plaintiffs’ plea to review the appeals court decision.

That decision was remarkable for a statement from Chief Justice Roberts that spelled out his doubts about applying the Antiquities Act to the seafloor – and his willingness to hear a new case on the issue.

“Which of the following is not like the others,” Roberts asked ironically in opening his opinion. “(A), a monument, (b) an antiquity (defined as a ‘relic or monument of ancient times,’ Webster’s International Dictionary of the English Language 66 (1902)), or (c) 5,000 square miles of land beneath the ocean?

“If you answered (c), you are not only correct but also a speaker of ordinary English.”

Roberts went on to review the expansion of presidential monument declarations since the early 20th century.

Obama’s use of the law to set aside federal waters the size of Connecticut “remains part of a trend of ever-expanding antiquities," Roberts wrote. "Since 2006, Presidents have established five marine monuments alone whose total area exceeds that of all other American monuments combined.”

The Antiquities Act originated under President Theodore Roosevelt in reaction to widespread looting of pottery from Pueblo sites in the Southwest. It enabled presidents to “declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated on land owned or controlled by the Federal Government to be national monuments,” according to the statute text.

“While the Executive enjoys far greater flexibility in setting aside a monument under the Antiquities Act, that flexibility, as mentioned, carries with it a unique constraint: Any land reserved under the Act must be limited to the smallest area compatible with the care and management of the objects to be protected,” Roberts wrote. “Somewhere along the line, however, this restriction has ceased to pose any meaningful restraint.”

The trend toward more expansive use of the Antiquities Act means it “has been transformed into a power without any discernible limit to set aside vast and amorphous expanses of terrain above and below the sea,” Roberts wrote. “The Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument at issue in this case demonstrates how far we have come from indigenous pottery.”

Roberts showed how the court could, under different circumstances, consider “how to interpret the Antiquities Act’s ‘smallest area compatible’ requirement…We may be presented with other and better opportunities to consider this issue without the artificial constraint of the pleadings in this case.”

Roberts noted there are five other cases pending in federal courts concerning national monument boundaries.

One of those fishermen involved in the previous court challenges, Jon Williams, owner of the Atlantic Red Crab Company, told the Washington Post that Roberts’ opinion is “a road map to the Supreme Court.”

Budi said fishermen’s work over the Northeast monument is far from exploitation the Antiquities Act was written to prevent. He says about 25 percent of the U.S. East Coast swordfish and longline tuna catch comes from the region.

“In our case we’re not stealing any pottery, and what we’re getting from there is legal,” he said. “And if we don’t use it, we’ll lose it.”