Federal agencies have put out a new plan to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whales, as the government promotes aggressive development of offshore wind energy projects.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and National Marine Fisheries Service released their joint strategy Oct. 21 “to protect and promote the recovery of North Atlantic right whales while responsibly developing offshore wind energy.”

The announcement initiated a 45-day public review and comment period on the draft strategy. Comments on the guidance can be submitted online via regulations.gov from October 21 to December 4, under Docket Number BOEM-2022-0066.

The plan comes out amid turmoil in the commercial fishing industry over NMFS plans for gear and area restrictions in the Northeast lobster fishery to reduce the danger of entanglement with whales. The Maine Lobstermen’s Association is challenging the plans in federal appeals court, as NMFS looks toward potential restrictions on other East Coast fisheries that use fixed gear like fish pots and gill nets.

Meanwhile opponents of offshore wind projects have set their sights on the right whales’ predicament as a strategy to use for challenging wind developers and federal agencies in court. Activists and lawyers organized by the Heartland Institute, a frequent critic of renewable energy programs, say right whales could be key to a challenge of Dominion Energy’s Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project.

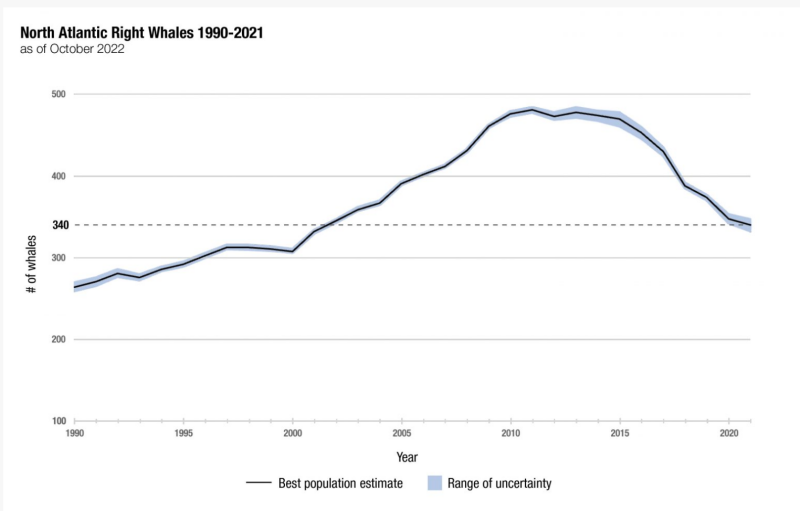

In a prelude to its annual meeting this week, the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium issued an updated assessment of the whale population numbers – all still pointing to the precarious state of the animals.

“Last year, using the best available data, the Consortium reported the 2020 population estimate to be 336 (+/-14 for range of error),” according to summary released Monday by the group.

After processing more photos from monitoring overflights in 2020, that estimate was adjusted to 348, plus or minus five, according to the consortium. This week’s updated report will drop that estimate back down to 340 animals, plus or minus 7 in 2021.

“The current population estimate represents a continued decline for the species, showing more individual whales died than were born,” according to the report preview.

“While it is certainly good to see the slope of the trajectory slow, the unfortunate reality is that the species continues to trend downward, with fewer than 350 individuals alive in 2021,” said Heather Pettis, research scientist in the New England Aquarium’s Anderson Cabot Center for Ocean Life and executive administrator of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium.

In their report, the scientists express concern about the 15 calves born in 2022.

“The number is lower than the 18 born in 2021 and far below the average of 24 calves per year in the early 2000s,” the summary says. “There were also no first-time mothers in the group, which supports the findings of a new paper on breeding females showing a downward trend in the number of female right whales capable of breeding.

"Research has also found concerning evidence of declining body size, in part due to frequent entanglements in fishing gear, with smaller female right whales producing fewer calves.

“With this new population estimate, the species number is now down to what it was around 2001. In the ensuing decade, the population increased by 150 whales; that tells us this species can recover if we stop injuring and killing them,” said Philip Hamilton, senior scientist at the New England Aquarium and the identification database curator for the Consortium.

The draft strategy by BOEM and NMFS lays out the agencies’ goals and objectives to better understand the effects of offshore wind development on the whales and their habitat.

“BOEM is deeply committed to ensuring responsible offshore wind energy development while protecting and promoting the recovery of the North Atlantic right whale. Working with NOAA Fisheries on this draft strategy leverages the resources and expertise of both agencies to collect and apply the best available information to inform our future decisions,” said BOEM Director Amanda Lefton. “We’re seeking open and honest feedback from the public to help us evaluate and improve this effort.”

The agencies’ document acknowledges that the loss of even one whale in a year can push the right whale population farther down the slope of decline.

NMFS declared an “unusual mortality event” after whale losses spiked in 2017, and since then it’s estimated 20 percent of the population has been affected by injuries and deaths, the plan notes.

“The actual situation is certainly much worse, with cryptic mortality (unobserved mortality)…estimated to be 64 percent of all mortality,” the plan states. “Based on this information, roughly 230 animals have died since the population peaked at 481 in 2011…Human-caused mortality is so high that no adult North Atlantic Right Whale has been confirmed to have died from natural causes in several decades; for a species that might live a century, most animals have a low probability of surviving past 40.”

Ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement are the primary human-caused mortality. Construction and operation of offshore wind turbine arrays would pose their own hazards, the plan says.

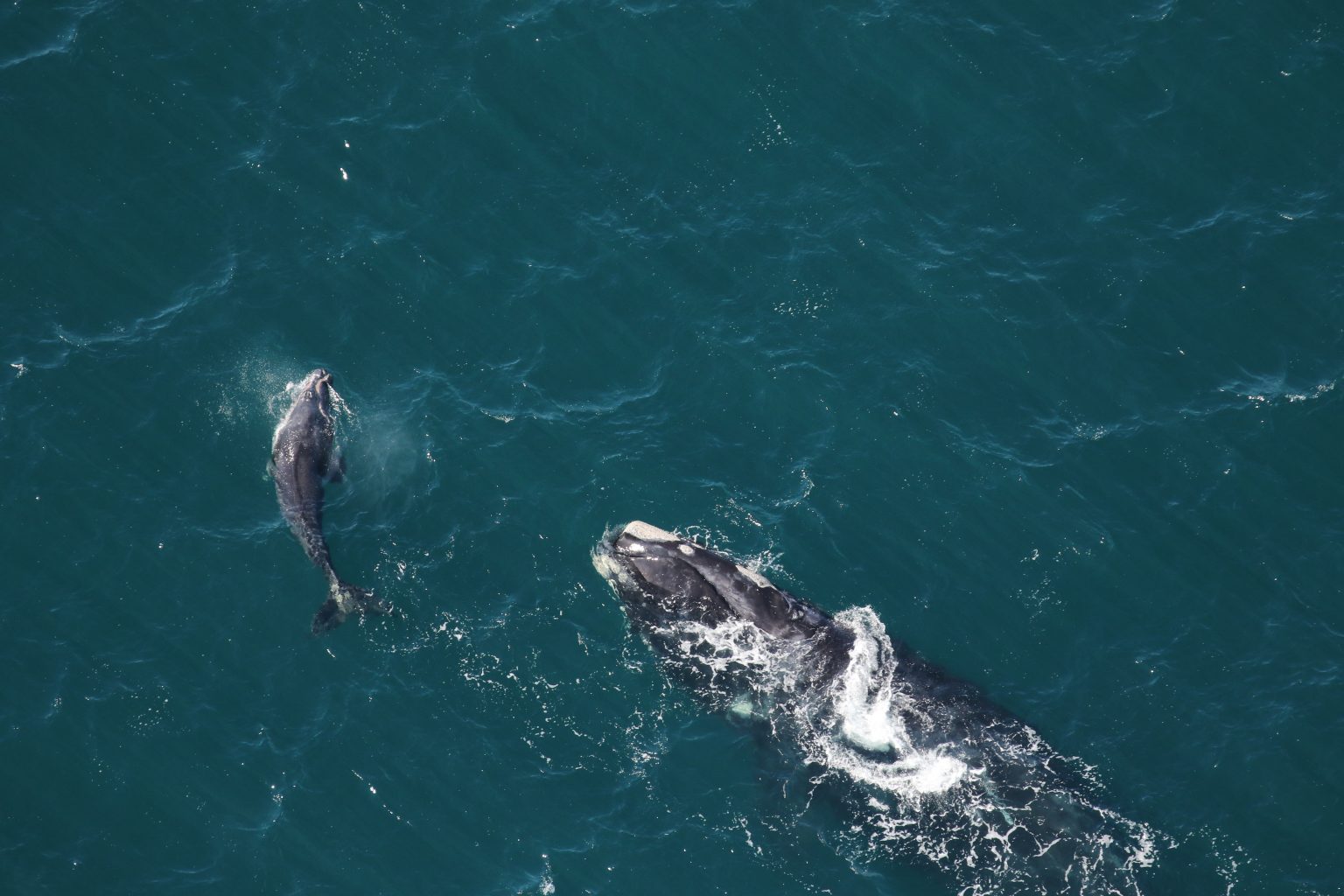

Whale researchers have documented right whales spending more time in southern New England waters in and around wind energy areas, and called for stepping up monitoring and mitigation measures with wind development projects.

The BOEM-NMFS strategy document names four “primary stressors” that wind development can put on the whales:

- Exposure to noise and/or pressure that could result in injury, hearing impairment, and/or behavioral disturbance – including detonation of unexploded ordnance such as World War II naval weapons found on the Northeast seafloor.

- Entanglement from cables, moorings, biological monitoring or displaced fishing gear.

- Increased risk from strikes by vessels involved in offshore wind projects, including construction, operations and maintenance, and potential shifting of other vessel traffic.

- Changes to habitat that may affect “the abundance, quality or availability of prey (e.g., changes in ocean circulation and mixing from in-water structures, including turbines and foundations, and impingement or entrainment of prey in cooling water intakes associated with High Voltage Direct Current cable systems) or attract predators (e.g., predators with an affinity for a new ‘reef structure’ in the environment).”