The Gulf Stream gives life on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. There’s warm water, abundant food for sea life and great fishing for people off North America. Thanks to its moderating influence on climate, they even grow small palm trees in Ireland.

A new study by European scientists show the Gulf Stream’s speed has slowed since the end of the 19th century and may be at its lowest in more than 1,000 years. If it continues, that could have immense effects of higher tides on the U.S. East Coast, fisheries and climate on both sides of the ocean.

Familiar to U.S. East Coast fishermen as the powerful warm-water stream from Florida up past the Grand Banks, the Gulf Stream is one part of what oceanographers and climate scientists know as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. It’s a key mechanism regulating global climate.

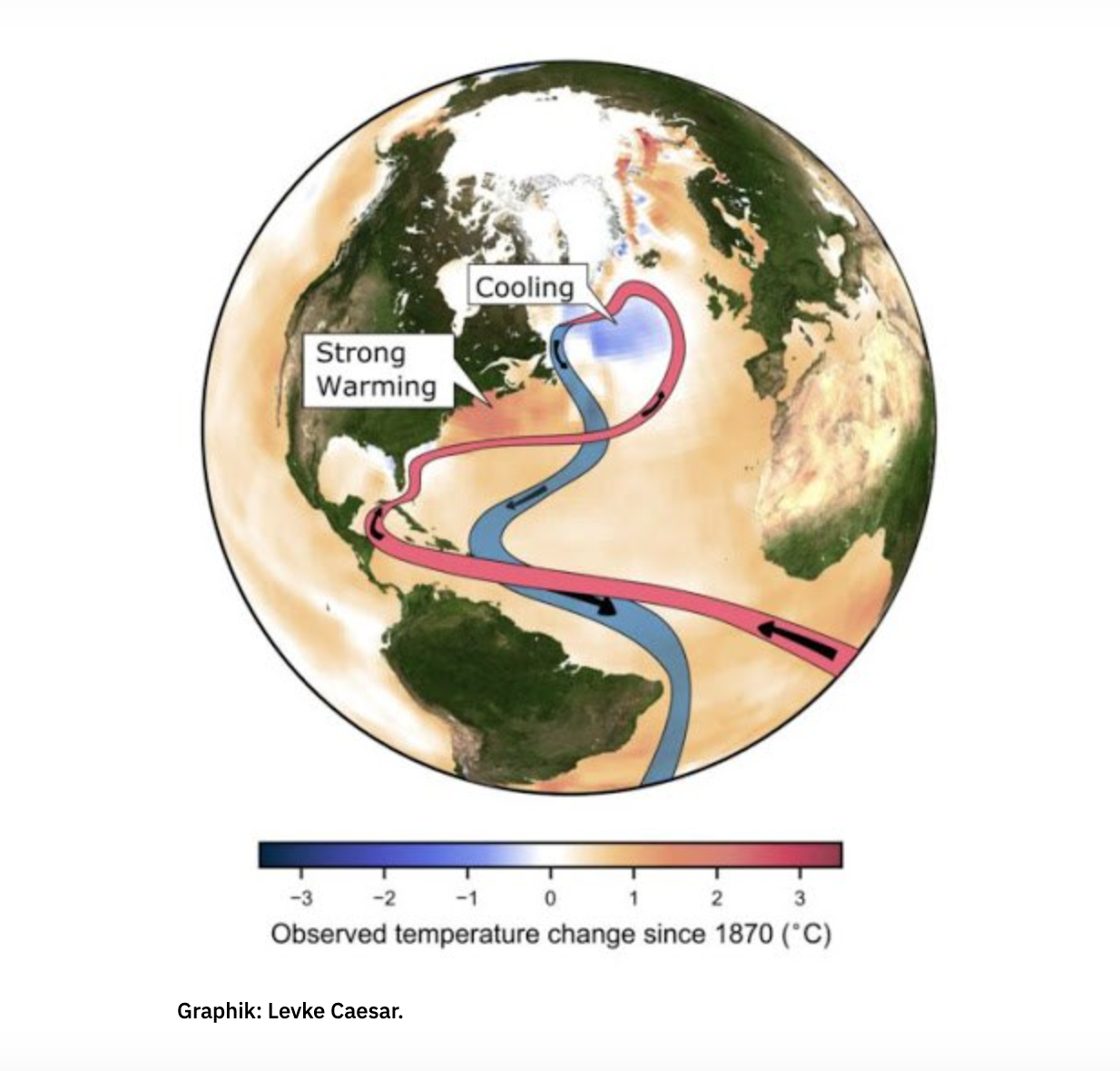

“The Gulf Stream System works like a giant conveyor belt, carrying warm surface water from the equator up north, and sending cold, low-salinity deep water back down south,” according to Stefan Rahmstorf of the from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who led a study published Feb. 25 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“It moves nearly 20 million cubic meters of water per second, almost a hundred times the Amazon flow,” Rahmstorf said in a statement from the Potsdam group, including scientists from Ireland, Britain and Germany.

Earlier studies by Rahmstorf and his colleagues, including a 2018 paper, showed a slowdown of the ocean current of about 15 percent since the mid-20th century. They linked this to human-caused global warming, “but a robust picture about its long-term development has up to now been missing,” the group said.

They used proxy data studies – looking at natural records that can be read from looking at ocean sediments or deep ice cores that allow scientists to look back centuries and reconstruct how the Gulf Stream and deep ocean flows changed in the past.

“For the first time, we have combined a range of previous studies and found they provide a consistent picture of the AMOC evolution over the past 1600 years,” says Rahmstorf. “The study results suggest that it has been relatively stable until the late 19th century. With the end of the little ice age in about 1850, the ocean currents began to decline, with a second, more drastic decline following since the mid-20th century.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations group that provides scientific assessments and updates, reported in 2019 that the AMOC is weaker relative to the 1850-1900 period.

The Potsdam group says their work provides independent evidence backing up that conclusion and longer-term context in climate history. Their study focused on temperature patterns in the Atlantic Ocean, subsurface water mass properties and deep-sea sediment grain sizes, dating back from 100 to ca. 1600 years.

Niamh Cahill, a statistician with Maynooth University in Ireland, tested the results and found that in nine out of the 11 data sets considered, the modern AMOC weakness is statistically significant.

“Assuming that the processes measured in proxy records reflect changes in AMOC, they provide a consistent picture, despite the different locations and time scales represented in the data. The AMOC has weakened unprecedentedly in over 1000 years” she says.

The potential for slowing the Atlantic conveyor has been predicted for years by climate change modeler as a response to global warming caused by greenhouse gases. The cycle is driven by deep convection of different ocean water densities. Warm, saltier water moving from south to north on the Gulf Stream, cools and sinks to deeper ocean levels, and slows slowly back to the south.

Increasing global average temperatures affect the cycle through increased rainfall and accelerated melting of the Greenland ice sheet. That adds more fresh water to the northern ocean, reducing salinity and density of the water, and thus weakening the flow, according to scientists. The trend has been linked to unusual cooling of the northern Atlantic over the past 100 years.

Should it continue, effects could be felt by people on both sides of the ocean.

“The northward surface flow of the AMOC leads to a deflection of water masses to the right, away from the US east coast. This is due to Earth’s rotation that diverts moving objects such as currents to the right in the northern hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere,” said Levke Caesar of Maynooth. “As the current slows down, this effect weakens and more water can pile up at the U.S. East Coast, leading to an enhanced sea level rise.”

Some scientists are already looking at whether permutations in the Gulf Stream might be a factor in a regional trend of more frequent high-tide flooding events in Charleston, S.C., Miami, Fla., and along the Southeast U.S. coastline.

In Europe, a further slowdown of the AMOC could bring more extreme weather events like a change of winter storm tracks coming off the Atlantic and intensifying them. Other studies found possible consequences being extreme heat waves or a decrease in summer rainfall.

“If we continue to drive global warming, the Gulf Stream System will weaken further – by 34 to 45 percent by 2100 according to the latest generation of climate models,“ said Rahmstorf. “This could bring us dangerously close to the tipping point at which the flow becomes unstable.”