A South Atlantic shortfin squid fishery is dominated by distant-water fleets off Argentina, primarily Chinese vessels that account for an estimated 69 percent of fishing activity, according to a new report by the environmental group Oceana.

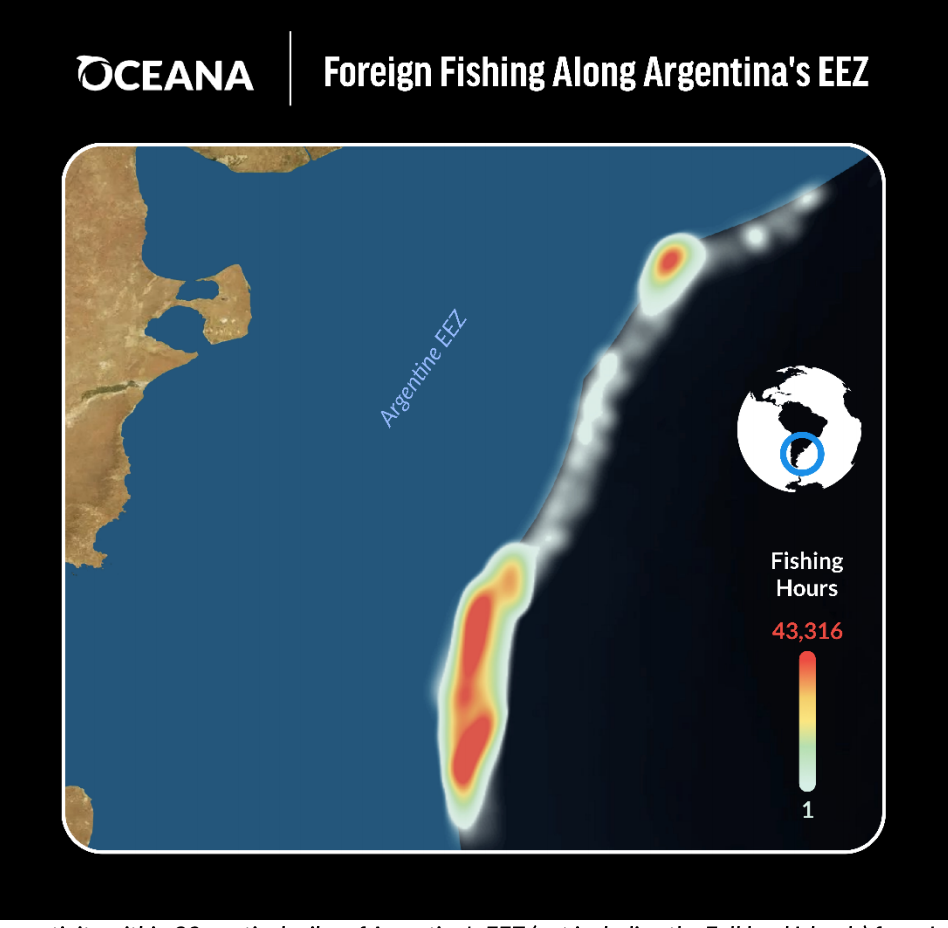

From Jan. 1, 2018 to April 25, 2021, the group documented more than 800 foreign-flag vessels logging more than 900,000 hours of apparent fishing activity, based on analysis of Automatic Identification System (AIS) data.

That analysis also showed vessels regularly “went dark” – apparently turning off their AIS transponders – effectively dropping out of sight for 600,000 hours in all. Some 66 percent of those outages involved Chinese vessels, raising the possibility of masked illegal fishing, such as intruding into Argentina’s exclusive economic zone, according to Oceana researchers.

The study used AIS data collected by Global Fishing Watch, an independent nonprofit founded by Oceana in partnership with Google and SkyTruth. Compared to the foreign fleets, 145 of Argentina’s fishing vessels conducted 9,269 hours of visible fishing in this area during the same period — less than 1 percent of the total estimated fishing effort .

“Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing threatens the health of the oceans. The vessels that disappear along the edge of the national waters of Argentina could be pillaging its waters illegally,” said Beth Lowell, Oceana’s deputy vice president of U.S. campaigns.

“The United States can take action to address IUU fishing by requiring that all seafood imports have catch documentation to demonstrate it was legally caught, implementing full-chain traceability, and making transparency a condition of import. AIS, when used continuously, can provide managers, governments, and the public more visibility of what is happening beyond the horizon and deter illegal activity,” said Lowell.

China’s distant-water efforts off South America have escalated, from 22 vessels in 2001 to 252 in 2015 and 503 by 2019, according to the South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization. Conflicts have escalated as well, with Ecuador authorities stepping up patrols against poaching around the Galapagos islands.

In April 2020 Argentina authorities reported catching about 100 squid jig vessels, mostly Chinese, fishing illegally in the nation’s waters with their AIS disabled.

South Korean, Spanish, and Taiwanese vessels conducted 26 percent of estimated fishing activity in the study with nearly 200 vessels. Almost “90 percent of the Spanish vessels that fished along Argentina’s national waters appeared to turn off their public tracking devices at least once, and Spanish vessels spent nearly twice as much time with AIS devices off as they did visibly fishing,” according to the report.

Some 56 percent of vessels that had gaps in their AIS data engaged in at-sea transshipment to refrigerated cargo vessels. “Transshipping at sea can be a weak link in the seafood supply chain, potentially allowing illegally caught fish to be mixed with legal catch,” according to Oceana.

Of the vessels with AIS gaps, 31% of them visited the Port of Montevideo, Uruguay, at the end of their trip. The port has been implicated as a stop “favored by vessels engaging in illegal activity,” according to Oceana.