For nearly half a century, Sansom has been the voice for and a face of the individual commercial fishermen in Florida as the longtime executive director of the Organized Fishermen of Florida. His 2022 award as a National Fisherman Highliner recognizes his lifelong work.

Growing up in the Pensacola area with its “big history of commercial fishing for generations,” Sansom says that heritage was the basis for his decades of advocacy.

“Protect the resource so you always have it there, and guarantee access to the commercial side and consumers,” said Sansom. “These are public resources, and everyone should have access to it.”

Fishermen and colleagues say Sansom’s efforts are why their community has survived in Florida, despite net ban campaigns of the 1990s and continuing political and development pressures.

Whether working with fishermen or politicians, Sansom was always straight-up with his answers and recommendations, as well as outlining options and obstacles, says Florida fisherman Gary Nichols, a 1998 NF Highliner. Sansom’s intricate knowledge of the legislative process was his superpower.

“It’s so easy to kill a bill in legislation, it’s a miracle we got anything done,” said Nichols.

Sansom, 75, lives in Rockledge, Fla., and handed off the executive director job to Alexis Meschelle a year ago. But he’s still involved, passing on his deep experience.

“We won’t go for anything that’s not biologically sound,” is one of Sansom’s rules. With degrees in marine science from Florida Tech and Florida State University, he could bridge the language for both fishermen and fishery managers.

Then in 1978, Sansom joined the Organized Fishermen of Florida as executive director. “The opportunity to be that involved, as a marine biologist, couldn’t be passed up,” Sansom recalled.

But that dashed any chance of relaxed cruising. As politics and population growth rapidly changed Florida, Sansom strove for decades to save Florida’s commercial fishing industry. Under unrelenting pressure from recreational fishing industry interests, that fight expanded across the Gulf of Mexico states.

In his first week on the job, a feud erupted between Florida’s commercial hook and line fishermen and gill netters. “That’s how I started the job, trying to resolve these kinds of conflicts,” said Sansom. “It was an interesting time.”

In the 1980s, crowding and competition in the spiny lobster fishery led the Organized Fishermen of Florida into proposing an ultimately successful solution to reduce the number of traps.

“We developed this project that was the first of its kind, really, and we did it with the help of the fishermen,” said Michael Orbach, a professor emeritus of marine policy at Duke University who worked closely with Sansom. “He has always been an absolute master of dealing with the fishing community.”

The spiny lobster fishery had been easy to enter in the 1970s. “It was very lucrative” and producing around 6 million pounds a year, said Orbach. But the trap numbers escalated rapidly to around 1.2 million, with diminishing returns for fishermen “by the time Jerry got involved,” he said.

Orbach had met Sansom while working on the evolution of federal fisheries management in the 1970s. “Jerry said, “Mike, we have a problem,’” Orbach recalled.

“The managers knew a lot about lobsters but not a lot about fishermen,” said Orbach, who is trained in anthropology, “so I work on the people side of fishing.”

After going out with and talking to fishermen on the boats, Orbach had the information that he and Sansom could present in meetings with managers and fishermen. They came up with a trap reduction plan.

Fishermen “all knew they could catch 6 million pounds with one-sixth of the traps,” said Orbach. Issuing transferable certificates for fishermen’s traps set a control limit, where no one individual or company could own more than 1.5 percent of the total, and gave fishermen equity investment in their gear worth about $100 a trap, said Orbach.

Florida state managers told the advocates a new state law would be needed, and Sansom got it done in 1990, said Orbach.

“He organized the best lobbying campaign I have ever seen,” with fact sheets listing names and faces of lawmakers and staffers for fishermen to contact at the state capitol in Tallahassee, said Orbach. “He had his fishermen come up and walk in wearing their white fishing boots.”

The spiny lobster program was so successful that it could have been a model for the stone crab fishery, too, Orbach and Sansom say. But soon Florida fishermen faced their doomsday crisis: the net ban.

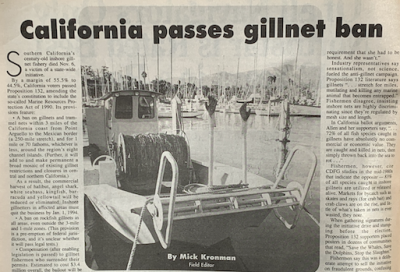

In 1990 California voters approved a state constitutional amendment to ban inshore gillnets, a measure pushed by a coalition of recreational fishermen and environmental activists. Sansom said that victory, and the rise of activist recreational groups like the Coastal Conservation Association, lit the fuse for what happened next.

“It goes back to California. When that passed, the Florida outdoor writers decided to use that as their blueprint,” said Sansom. As on the West Coast, net critics’ publicity campaign blamed commercial fishermen for depleting stocks – and for the non-recreational-fishing audience, accused them of endangering marine mammals.

Some commercial fishermen refused to countenance any kind of compromise to defuse the fight. “But a lot of them had fallback positions for income,” and could afford to take that risk, he says.

Sansom warned his membership against a fight to the finish: “If Custer knew then what we know now, he wouldn’t have done it.”

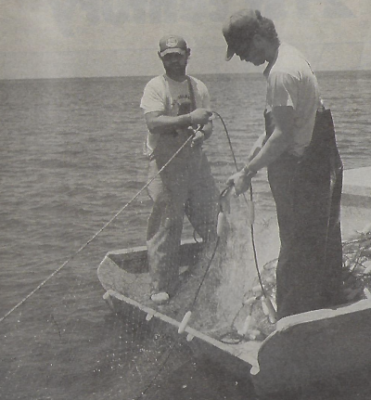

In November 1994, 72 percent of Florida voters approved a state constitutional amendment to ban entanglement nets in nearshore and inshore waters, aimed mostly at the then-thriving mullet fishery. The ban took effect July 1, 1995, pushing net fishing three miles off the Atlantic Coast and nine miles into the Gulf of Mexico.

“There are people out there right now who are suicidal,” Sansom told one reporter a month later. “There are people who are totally withdrawn. There are people who have lost all will to live, people who are incredibly angry.”

Hardest hit were the full-time fishermen in traditional coastal villages, without other employment to fall back on, Sansom said.

Karl Wickstrom, the founding publisher of Florida Sportsman magazine, was a central figure in organizing recreational writers to push the net ban. Wickstrom “believed fishing should be like wild game,” banned from commerce, said Sansom. “He didn’t believe in any rights for consumers.”

Commercial fishermen could be lulled into believe there was little danger based on the support they long enjoyed in their coastal communities.

“Twenty miles down the road, it was a different story” in Florida’s burgeoning suburbs and retirement communities, said Sansom. There was a ready audience for the anti-netting, “walls of death” rhetoric that had been pioneered in California.

To their credit, “the Legislature and the agencies fought this really hard,” said Sansom. But it was no match for the publicity machine backed by Wickstrom and recreational groups like the Coast Conservation Association.

Gretchen Coyle, a Beach Haven, N.J. writer, spent winters on Useppa Island in southwest Florida starting in the 1980s and saw the net ban’s impact on local fishing families. Coyle had met them out on the water – like the time her small boat got stuck at night, with just her and her Old English sheepdog on board, and was towed off by a local captain.

“It just showed they were really good people,” said Coyle. But as the net ban took hold, the damage was evident in the mid-1990s. The politics even changed how some locals viewed fishermen. Coyle recalled an incident when her car was broken into at a marina, and a sheriff’s deputy was dismissive: “Oh no. It’s fishermen. They’ll take anything.”

“That was so sad. I didn’t understand it. These guys were from five generations of going out in small boats and selling fish by the side of the road,” said Coyle. After the net ban, “I could see boats for sale by the side of the road. You could tell people were hurting. I really felt bad for those families.”

“Outside of the heart of the fishing community, that’s exactly what happened,” Sansom confirms. “Totally unjustified, but you get people into a frenzy. That’s what Karl Wickstrom and the writers thought they had to do.”

State officials anticipated 1,500 displaced fishermen would need training and re-employment assistance. Organized Fishermen of Florida managed to persuade state officials to budget $40 million for a two-year transition period for job training and gear buy-backs, said Sansom.

Officially retired, Sansom is still a resource for the OFF and its members.

“I came on in June of last of the year, and Jerry has been mentoring me ever since,” said Alexis Meschelle, now executive director of the Organized Fishermen of Florida. Like Sansom’s longtime compatriots in the group, Meschelle says Sansom’s institutional knowledge of government policy-making and legislative procedure is beyond value.

“Right now, we’re rebuilding and trying to get back on track” to adjust with recent changes in Florida law and regulations, particularly on the stone crab fishery, said Meschelle, whose husband Nathan fishes for stone crab, mullet, and other species. “There have been a lot of changes.” Environmental issues are another top concern now for OFF’s 250-plus members.

“We’re working more on the impacts of water quality,” said Meschelle. Recurring red tides and escalating pollution loads coming out of Florida’s burgeoning suburban communities are triggering fishery and beach closures, and fishermen regularly pitch in to help state and federal agencies track algae blooms.

After the angry 1990s, Florida’s fish politics began to settle down after 2000. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has “made it a point to treat the commercial fishermen fairly,” said Sansom.

“The new Florida conservation commission has been pretty straight up. It hasn’t been easy,” he added. “But they recognize the value of the commercial fishery.”

Looking back, Sansom says, “I think I was the right person for the job. I was glad I had it."