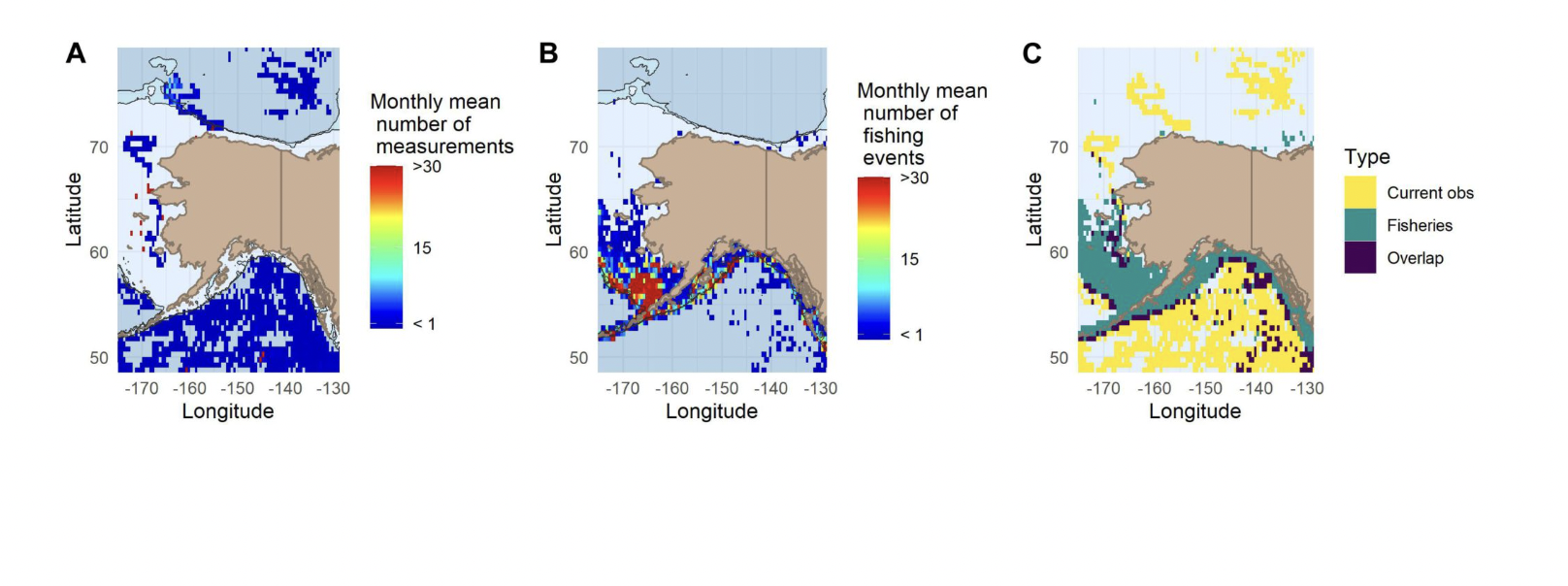

A growing network of commercial fishing boats and private companies are using sensors attached to fishing gear to cheaply collect crucial ocean data like temperature and salinity, used in fisheries science, climate models, and more. Traditionally gathered at great expense by research vessels, moorings, and gliders, data gathered by fishing boats offers ocean observers a cost-effective way to increase their coverage.

“Word has spread in the scientific community that we’re offering affordable fieldwork,” said Jim Moore, board member of the Alaska Trollers Association (ATA). “Here our interests converge: the better the science, knowledge based on reality, the healthier the relationship between fisheries and managers.”

Moore is working to outfit 10 ATA boats with marine observation equipment as part of a grant-funded pilot program, one of many such collaborations between ocean observers and fishermen around the country. Ocean Data Network (ODN) a Maine-based data collection company recently named as a winner in the World Economic Forum’s Ocean Data Challenge, will be the back-end data management team, exemplifying the aligned interests of fishing and science.

“It’s not only that it's more cost effective,” said Cooper Van Vranken, founder of ODN, “but it’s also that the fishing is getting data in the oceanographically most interesting areas and in the areas where it matters most for fisheries and for all kinds of other users. The future of ocean observation is a symphony of different observing platforms and fishing vessels are going to be a very important piece of all that.”

“What are the benefits to our fleet from our developing and participating in this project?” Moore said. “A good troller is a natural scientist…and when we get it right, we are rewarded by a nice catch at the end of the day. That’s applied science.”

Temperature and salinity are the most widely used ocean variables, and primarily what ODN’s sensors are measuring, according to Van Vranken.

"Temperature is good to measure because it can give you information on if the thermal tolerances of fish or other marine organisms are being stressed,” said Tyler Hennon, assistant research professor at University of Alaska Fairbanks College of Fisheries and Ocean Science, “measuring salinity and temperature together gives you important clues on how water is circulating."

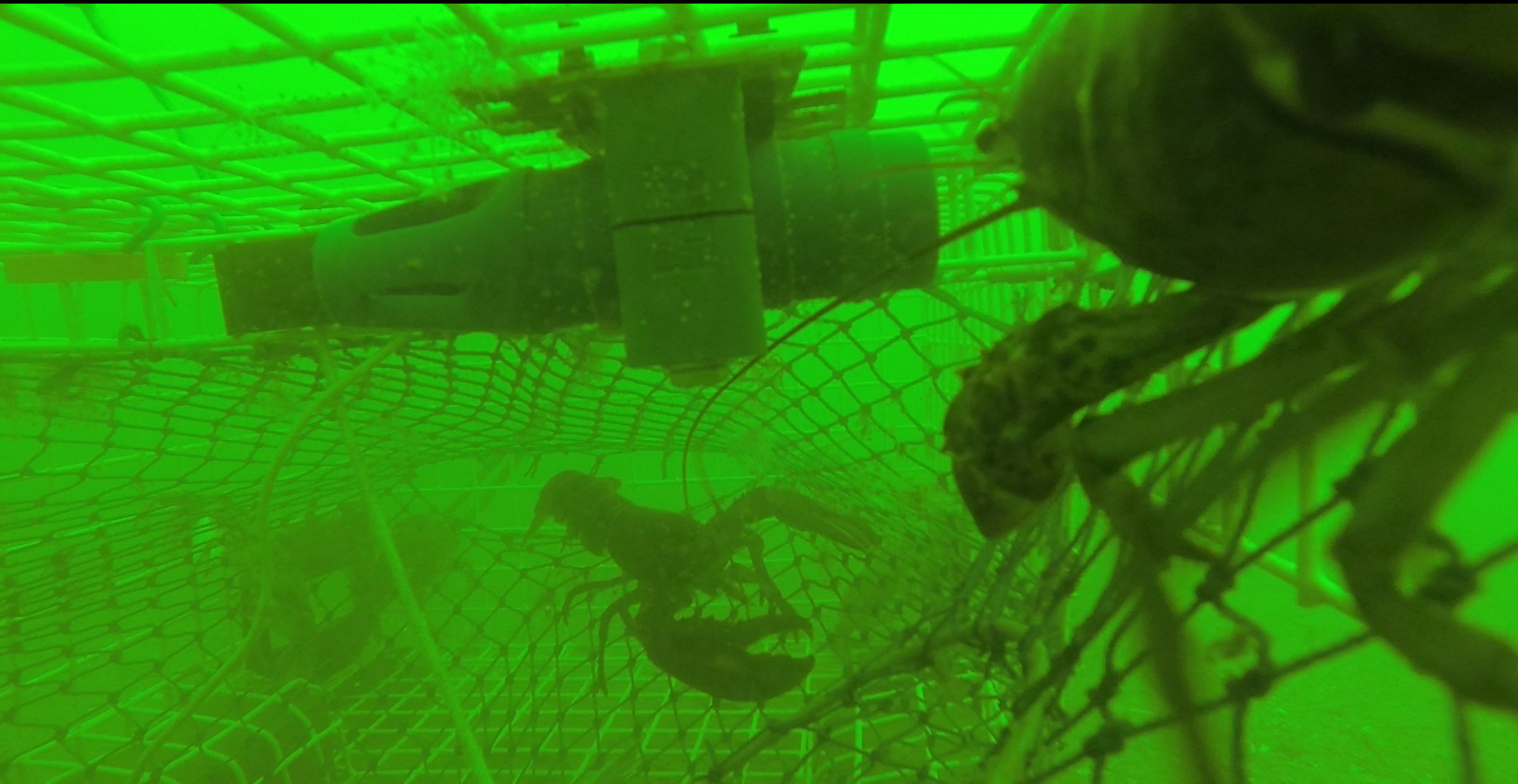

When an ODN sensor comes out of the water with fishing gear (depending on the type of gear and data being measured, this process varies in some ways), it transmits its measurements automatically via Bluetooth to a receiving unit on deck, which then relays the data to ODN. There it is processed and passed on to clients ranging from the Office of Naval Research to Gannet Nets.

“That’s all autonomous,” said Jack Carroll, director of operations and technical development at ODN, “there’s no effort put in by the crew at all, which is key, because we don’t want to interfere with their operations. From that collection hub either via satellite internet or cell service the receiver sends the data to our end point.

"From there we clean up the data and forward it to whatever end user it may be, depending on the project and what they want to do with it.”

Captain Mark Phillips, whose fishing vessel Illusion records temperature in the Mid-Atlantic Bight as part of ODN’s contract with The Office of Naval Research, says the sensors don’t interfere with him catching squid, and the temperature information can be useful in real time.

“It’s one more piece of information to the puzzle,” Phillips said.

The collaboration between ocean observers and commercial fishermen is the result of aligned interest in collecting data: it’s comparatively much cheaper to attach sensors to fishing vessels than to use research ships, and fishermen benefit from improved observation of their fisheries.

“It allows us to get more spatial coverage for very little cost,” said NOAA oceanographer James Manning, who started the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Environmental Monitoring on Lobster Traps program. “Where research vessels that travel the shelf only go out at most once every season, they get a lot of good data all through the shelf, but it’s not very often, so we fill in shorter time scales. The research vessels can’t capture that.”

“The King Crab collapse in the Bering Sea is a case in point,” Van Vranken said. “Nobody knows what’s going on up there. There’s all these theories and finger-pointing, many people are saying its temperature related, but there’s so little data up there so the industry is flying blind. Science, management, and industry all need more solid data to know what’s happening, and even to have a sense of what is likely to happen in a few years.

"That is essential for making business decisions and to be able to know if this a fluke or the new normal. Our integrated data collection is the cornerstone for building that type of resilience and preparedness.”