Researchers around the world are using AI and machine learning to identify and avoid bycatch.

Call it inevitable. If doctors are using artificial intelligence (AI) to read X-rays and MRIs, how long could it be before fishermen could use AI to identify bycatch?

While AI assisted bycatch control systems are not yet fully operational and on the market, they are close, and a number of U.S. and European players are collaborating on development.

“We’ve got a network of people all working on this,” says Noelle Yochum, a former NOAA bycatch reduction expert, now working for Trident. “We’re sharing information in the hopes of getting at least one over the finish line.”

While Yochum’s primary concern has long been halibut and salmon bycatch in the Alaska pollock fishery, the problem is worldwide. The current estimate of global discards in commercial fisheries is 27.0 million metric tons, with a range of from 17.9 to 39.5 million mt.

“I read that the value of that was somewhere around $84 billion US dollars,” says Hege Hammersland, Business Development Manager for Scantrol Deep Vision, a Norwegian company using AI to help reduce bycatch.

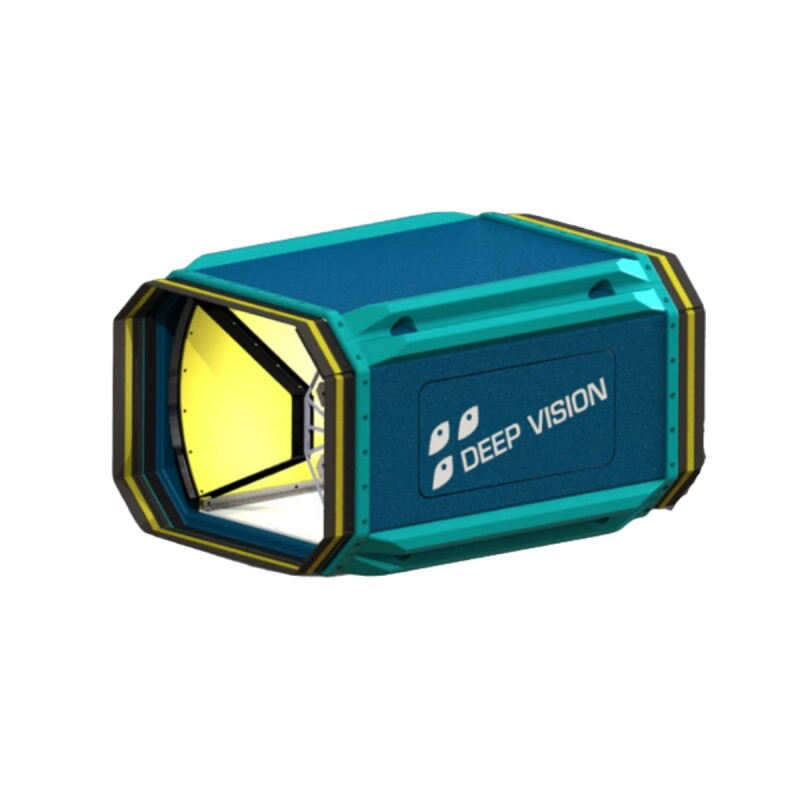

“Scantrol Deep Vision started about 10 years ago,” says Hammersland. “We developed a big box camera system that we commercialized for research in 2017.” According to Hammersland the company collected millions of images from the research model and used those to teach the unit’s computer how to identify size and species. “We’re working with a Spanish company, Gerona Vision Research, that specializes in machine learning.”

With its success in the research sector, Scantrol Deep Vision has develope a newer smaller model for commercial fishing vessels. “It’s a cylinder about half a meter long with an acoustic sensor that triggers the camera when a fish or anything comes past,” says Hammersland. Equipped with lights and stereo camera the Scantrol Deep Vision unit can take rapid photos of fish entering the net.

“Right now, we are collecting the information and uploading it after we bring it aboard,” says Hammersland, noting that the company is working with fishermen to refine ways to use the equipment within the constraints of actual fishing operations. “We are working on finding the sweet spot between the number of images needed, and battery life.”

Hammersland notes that future development will include real time transmission of data to the skipper, and mechanisms to allow bycatch to escape. “We are a year or two away from making this available on the market,” she says.

On the other side of the Skaggerak, the strait between Norway and Denmark, Ludvig Ahm Krag, a former commercial fisherman turned researcher, and now professor of fishing gear innovation at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU-Aqua), is working with Atlas Meridan, Marport, and other collaborators on a net mounted video camera that can reduce bycatch, and increase efficiency by helping fishermen fish where the fish are.

“Our first challenge was getting clear images,” says Krag, noting that clouds of sediment stirred up by the sweep and groundlines of a net often made it impossible to capture clear images. “We found that if we put a tarp behind the sweep and then mounted the camera inside a tunnel, we could get clear images,” he says.

The DTU camera, developed my Atlas Meridan, uses a coaxial cable to power and control the unit and transmit video images to the wheelhouse. “But the captain has other things to do,” says Krag. “So, we train the machine to identify, what is a nephrops [a type of small lobster], what is cod, what is whiting. We put a little box around the image and tell the machine, this is cod, or what have you.”

Getting the images right is the first step in what Krag believes will be rapid advances in AI use in fisheries.

“Trawling is 95 percent of our catch,” he says. “And nephrops is the most valuable. But sometimes they are up and sometimes they are in their burrow under the mud. If a captain can see if he is catching nephrops he can keep fishing, but if the nephrops are in the mud, he does not have to waste his time.”

But even when the nephrops are out of the mud they can’t be seen with sonar. “The nephrops do not have an acoustic signal, like fish,” says Krag. This technology will help fishermen know if they are making money or not. No one can afford to be inefficient these days.” Krag adds that in the future the technology will enable fishermen to know exactly what they are catching in terms of species, size and quantity and help determine if they are making money or not.

At the same time, Krag notes, the imagery can help fishermen avoid choke species like cod. “It can also be used in marketing, if you can show that you have less than 2 percent bycatch it becomes a selling point.”

Krag at DTU, and Hammersland at Scantrol Deep Vision are hardly alone in their efforts, and both are looking at how to get unwanted bycatch out of the net in real time. Trident’s Noelle Yochum is working to loop all the players together to accelerate the arrival of effective bycatch reduction and efficiency enhancing technology.