The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and offshore wind energy developers are pledging to do better by commercial fishermen – with fisheries studies, scout boats to head off survey conflicts with fishing gear, and bringing on highly experienced and respected fishermen as industry liaisons.

Incidents of survey boats towing through fixed gear in Mid-Atlantic waters are putting those processes to the test. Conch and black sea bass trap fishermen who have had gear damaged off the Delmarva coast and New Jersey brought their complaints to the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

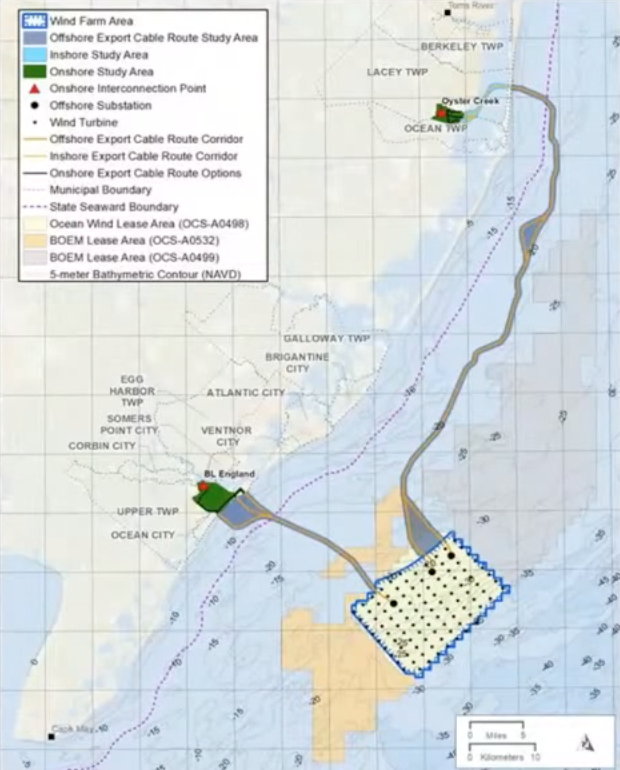

At an April 5 briefing Amanda Lefton, director of the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and wind developers Ørsted and Atlantic Shores updated the regional fishery management council on plans for two adjacent turbine projects off Atlantic City and Long Beach Island, N.J. – and BOEM’s recent $4.37 billion sale of New York Bight wind leases that could become even bigger arrays farther out on the continental shelf.

Then they heard from fishermen who have seen their conch and black sea bass gear dragged and damaged by survey vessels working on wind leases off New Jersey and the Delmarva peninsula.

New Jersey captain Joe Wagner Jr. told the council how he lost 157 bass traps in 2021 during a survey around the Ørsted Ocean Wind project area.

“The only reason I got somewhat of a payment (compensation) is because I caught their vessel at 3 o’clock in the morning pulling three of my high flyers behind their boat,” said Wagner.

Jimmy Hahn, a conch fisherman from Ocean City, Md., said there needs to be accountability for damages, disruption of fishing seasons and displacement from longtime fishing bottom.

“We need somebody we can call,” said Hahn, who described circular referrals of his complaints around the Coast Guard, BOEM and the National Marine Fisheries Service. In November 2021 Hahn was involved in a face-off with a survey boat for U.S. Wind that he said at risk of overrunning his gear.

“Obviously they can’t work around my gear,” he said. “The fishermen have to be compensated for losing their bottom.”

“We’ve got a long time ahead of us,” said Hahn. “We need to figure out right now who is going to hold the wind farms accountable.”

Off the New Jersey coast, Ørsted and Atlantic Shores leases lie in waters used by trap and pot fishermen, draggers, gillnetters and surf clam vessels.

Ørsted is paying for fisheries monitoring work with Rutgers and Monmouth universities, employing captain Jim Ruhle’s trawler Darana R from Wanchese, N.C., and the surf clam vessel Joey D.

Fisheries liaisons are working with survey crews to avoid conflicts and scout vessels are being employed, said Ross Pearsall, fisheries relations manager for Ørsted. The company’s stated goal is “trying to resolve any conflicts with individual fishermen quickly and fairly.”

In those heavily used waters, keeping up-to-date communications with fishermen is labor-intensive.

“I talk to these guys almost daily,” said Kevin Wark, a longtime Barnegat Light, N.J., gillnet captain and fisheries liaison for Atlantic Shores, the planned 1,510-megawatt turbine array off Long Beach Island that’s a joint venture of Shell New Energies and EDF Renewables North America.

It’s critical to keep up close contacts with area fishermen, and the survey crews who will be working those waters, he said.

Wark said fishermen “are under a lot of stress daily” from planning around weather, fishing regulations and market conditions. For the survey boat captains and crews, “they’re very worried about interactions” with fishing gear, he said.

Those waters have black sea bass and lobster trap fisheries, and fixed monkfish gillnets in season. The mobile drift gillnet fishery has declined somewhat in recent years and surf clams are shifting with climate changes.

A lobster fisherman had damage from a survey tow but was satisfied with a reimbursement, said Wark.

A cable survey in fall 2021 over a 25-mile reach was planned ahead by talking to fishermen and the survey crew to have it completed before the start of monkfish season with its set gillnets, he said.

“They knocked that thing out so by the time everybody went fishing, they were done,” he said.

“It can be done, it’s a lot of work, a lot of communication, but we can avoid gear problems I think for the most part,” said Wark. “It takes communication between the survey vessel and whoever’s doing the liaison work, you’ve really got to be on it.”

After BOEM’s record-setting New York Bight wind auction in February, the agency is now in the process of “winnowing” potential wind energy areas off Delaware south to Cape Hatteras, N.C., considering factors including navigation, fisheries, the route of the Gulf Stream, and protected species like loggerhead turtles, said BOEM director Lefton.

That process reduced the initial study are by 68.5 percent, and took down the subsequent planning area by 31 percent. BOEM is looking to publish a “call area” to elicit wind energy developers’ interest in the region, with an eye to holding a lease auction in the third quarter of 2023, said Lefton.

Council member Dewey Hemilright, a commercial fisherman from Wanchese, N.C., told Lefton that a big potential conflict with the pelagic longline fleet could lurk in the central Mid-Atlantic.

“I would venture to say that probably 25 percent” of the longline boats from Texas to the Carolinas fish in the region,” said Hemilright. Pelagic longlining and other floating gear can’t work around wind turbine arrays, he said.

“There’s probably only about 60 active boats left, and I’d hate to see them go away,” said Hemilright.

Those areas under consideration for wind power “are going to get smaller,” said Lefton. BOEM officials are aware of the longline fishery’s movements and considering it in their planning, she said.

A system to justly compensate fishermen for their work lost to wind power development, and to mitigate the effects long-term, still needs to be assembled. BOEM and NOAA are working on a framework for how compensation and mitigation funding will be required for wind developers’ construction and operations plans.

But despite sums being paid for developers for federal wind leases – like the unprecedented $4.37 billion for BOEM’s New York Bight auction – it would take an act of Congress to redirect some of that money into dealing with wind energy’s impacts. By law it all goes straight into the U.S. Treasury, said Lefton.

The $4.37 billion for New York Bight leases “is only going to come from (electric) ratepayers,” said Jeremy Firestone, a University of Delaware professor and expert on offshore wind development. He asked “if BOEM is working to get legislation” that would enable “distributive justice” for fishermen and communities that will be affected by wind projects.

“We do have these impacts,” said Firestone, “and we have a lot of money.”