Six offshore wind lease areas in the New York Bight are more than 30 miles offshore of the region’s bustling suburbs and seaside resorts – distance that might have defused resistance to the wind energy projects before.

Now opposition groups that grew in reaction to nearshore projects, like Ørsted’s cancelled Ocean Wind plan off New Jersey, show few signs they will accept a new round of proposals farther east to the horizon.

Over 100 visitors walked through a Bureau of Ocean Energy Management public scoping session Feb. 8 in a Toms River, N.J., hotel meeting room, talking to BOEM workers and giving the agency testimony in video interviews and writing. The agency has grown to prefer the low-key scoping process – in-person and online – to fulfill its legal obligations to gather public input short of full-blown public hearings.

The visitors were not shy with opinions.

“What we’re really worried about is the cabling. It’s death,” said Ed Baxter, a commercial fisherman with the Fishermen’s Dock Cooperative in Point Pleasant Beach, N.J.

The offshore leases now being planned for wind power development would need turbine towers linked by a network of power cables, and linked by energy export cables coming ashore near New York City and Sea Girt, N.J. A future cable network would potentially shut mobile gear fisheries like scallop dredging out of those routes, if fishermen can’t be safe that their gear won’t snag on cables, said Baxter.

The small Ørsted Block Island Wind Farm demonstration project of five turbines has had problems maintaining adequate sediment coverage over its cables. Problems with maintaining cable depth have been reported with the ongoing Vineyard Wind project too, said Baxter.

In the New York Bight, cable routes could run near the Mud Hole, a shallow trench between the ship traffic lanes south of New York Harbor. A rock and sand ridge on the west side of the Mud Hole is known as the Rock Garden among fishermen, and is very productive, said Baxter.

Baxter said he and many fishermen learned their trade there at the Mud Hole, but it can all be endangered by offshore wind development.

Fishermen are concerned too with future offshore substations and their cooling water systems, which handle water at 86 to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, said Rose Willis, Baxter’s wife. They are trying to find out what anti-fouling chemicals may be in the water systems, without much success so far, she said.

“We were important during the pandemic, when we were feeding people,” said Baxter, recalling when the fishing industry and federal government worked together during covid-19 to steer more seafood into retail markets during 2020. “To even play this game – how did we get here?”

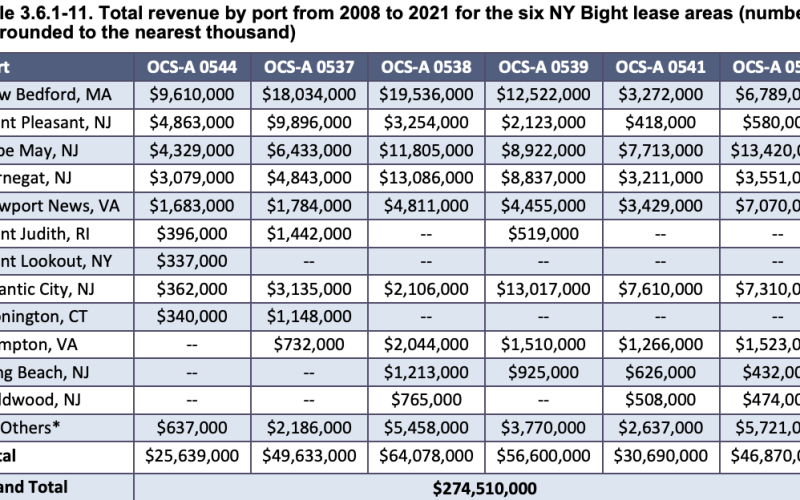

Deep in 790 pages of BOEM documentation is an estimate by NOAA Fisheries of the value of landings from the six lease areas between 2008 and 2021: $274.5 million, with scallops topping the list of value.

Tallies are modeled “using Vessel Trip Report (VTR) and vessel logbook data to estimate catch and landings based on the percentage of a trip that overlapped with each lease area,” according to BOEM documents. But the numbers are far too low, said Gus Lovgren, a captain with the Point Pleasant co-op.

“They’re not taking averages. They’re taking the lowest years they can,” said Lovgren. NOAA Fisheries itself won’t use VTR data in stock assessments, he added.

The scoping sessions are part of BOEM’s draft ‘programmatic’ environmental review of the New York Bight lease areas – a new step in the agency’s planning process, aiming to address issues on a regional basis that can then be incorporated in future construction and operations plans for individual projects.

The programmatic analysis approach has evolved after years of critics complaining that BOEM should have taken such a big-picture approach earlier in the Northeast, where offshore wind leases are clustered off southern New England.

BOEM took the new tack in the Gulf of Mexico, mounting an analysis of potential lease areas off Louisiana and Texas. The agency gathered information from Gulf stakeholder groups, identifying areas that should be set aside from potential wind energy development. That led to carve-outs of productive shrimp fishing areas offshore, and important migratory bird routes and habitat.

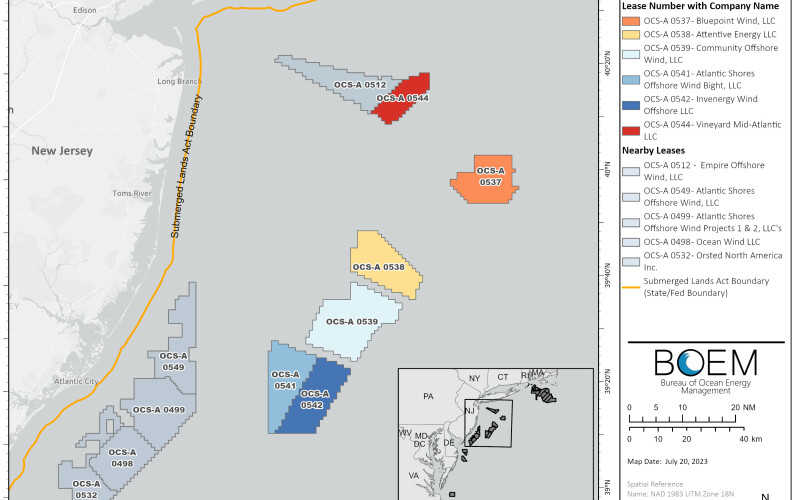

Now the programmatic approach is being applied to the New York Bight, where almost 490,000 acres could be developed beyond the ship traffic separation lanes from New York Harbor.

“It lets us think about the area a little more holistically,” said Jennifer Bosyk, branch chief in BOEM’s Office of Environmental Programs. The six lease areas are close to each other, sharing some of the same environmental and marine species characteristics, and their developers’ construction and operations plans can be expected to come before BOEM for review within a couple of years of each other, she said.

Developing the programmatic environmental impact statement, or PEIS, will establish a common baseline of knowledge so developers “can lean on what we’ve already done,” said Bosyk.

At one exhibit, BOEM landscape architect John McCarty showed posters with simulated visual images of how the tops of wind turbines could be glimpsed, even more than 30 miles from shore, depending on weather conditions like humidity and cloud cover.

Earlier visuals generated for inshore projects, like the Atlantic Shores turbine array that would be as close as 9 miles off Brigantine, N.J., helped stir support for local community opposition groups.

That opposition fueled conflict with New Jersey Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy, whose administration made Atlantic Shores and nearby Ocean Wind a centerpiece of state energy planning. Brigantine residents saw a delay of beach replenishment in their town until summer 2023 as payback, said Lisa Daidowe of the group Defend Brigantine Beach.

Meanwhile, “the GAO (Government Accountability Office) is still doing the review” of BOEM’s overall planning processes, said Daidowe.

The visual impacts of Atlantic Shores has been a major issue for the group Save Long Beach Island. One of the group’s slogans, ‘Move them 35 miles out,’ is prominent on billboards and law signs.

On Jan. 24, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities took a step toward developing the New York Bight leases, when commissioners approved the Leading Light project, a venture by Invenergy and energyRE, and Attentive Energy 2, backed by TotalEnergies and Corio Generation.

With a future total nameplate rating of 3,772 megawatts, the awards are an effort by New Jersey officials to get the state’s ambitious renewable energy plans back on track after Ørsted’s sudden withdrawal from its Ocean Wind 1 project Oct. 31.

In a Jan. 29 statement, SaveLBI called that action “a positive sign to see the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities putting forth two new proposed projects farther out in the Hudson South area for environmental review, where they should actually appear as ‘specks on the horizon’ as Governor Murphy has promised. The BPU orders on the projects recognize that both projects would not impact the shore communities and shore based tourism.”

Still, the group expressed caution about fishing and other environmental impacts – while calling for New Jersey to abandon nearshore wind development.