Our skiff picks up speed on the Intracoastal Waterway, accelerating out of view of the docks of McClellanville, S.C., into the unbroken salt marsh landscape. Spartina alterniflora, or smooth cordgrass, stretches into the horizon, and our route is closely followed by brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) and common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). We enjoy the wildlife show from our perches at the fore and aft of our vessel, a steady wind tousling the thick woven bags filled with sundried oyster shells loaded carefully around our legs. Jack Spahr keeps both feet firmly grounded as he navigates these waterways, familiar enough to him after nine months of this commute as a full-time waterman working alongside his uncle. He laughs easily with Garrett Kestory, one of the lucky six selected out of 59 applicants to participate in the inaugural class of the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium’s (Consortium) month-long Commercial Seafood Apprenticeship Program (CSAP).

We follow in the wake of Jack’s uncle, Captain Jeff Spahr, owner-operator of Charleston Oyster Company and McClellanville oysterman for 21 years, as he navigates intertidal creeks with our other apprentices: Bekah Bennett, Blake Godsey, Shane Brackett, Jamie Deese, and Patricia Ann Cope. We zip along the western edge of Jeremy Island, then head east along the waterway toward the Atlantic Ocean. After two weeks of marine navigation lessons, knot-tying, small engine repair, CPR, First Aid and automated external defibrillator certification, a U.S. Coast Guard Drill Conductor certification, and emergency water evacuation training, everyone is glad to be on the cool water. A bend brings our vessels parallel, and apprentices jokingly wave to one another under the April sun. With recreational fishing licenses in hand, we are ready to be immersed into the art of wild oyster harvesting.

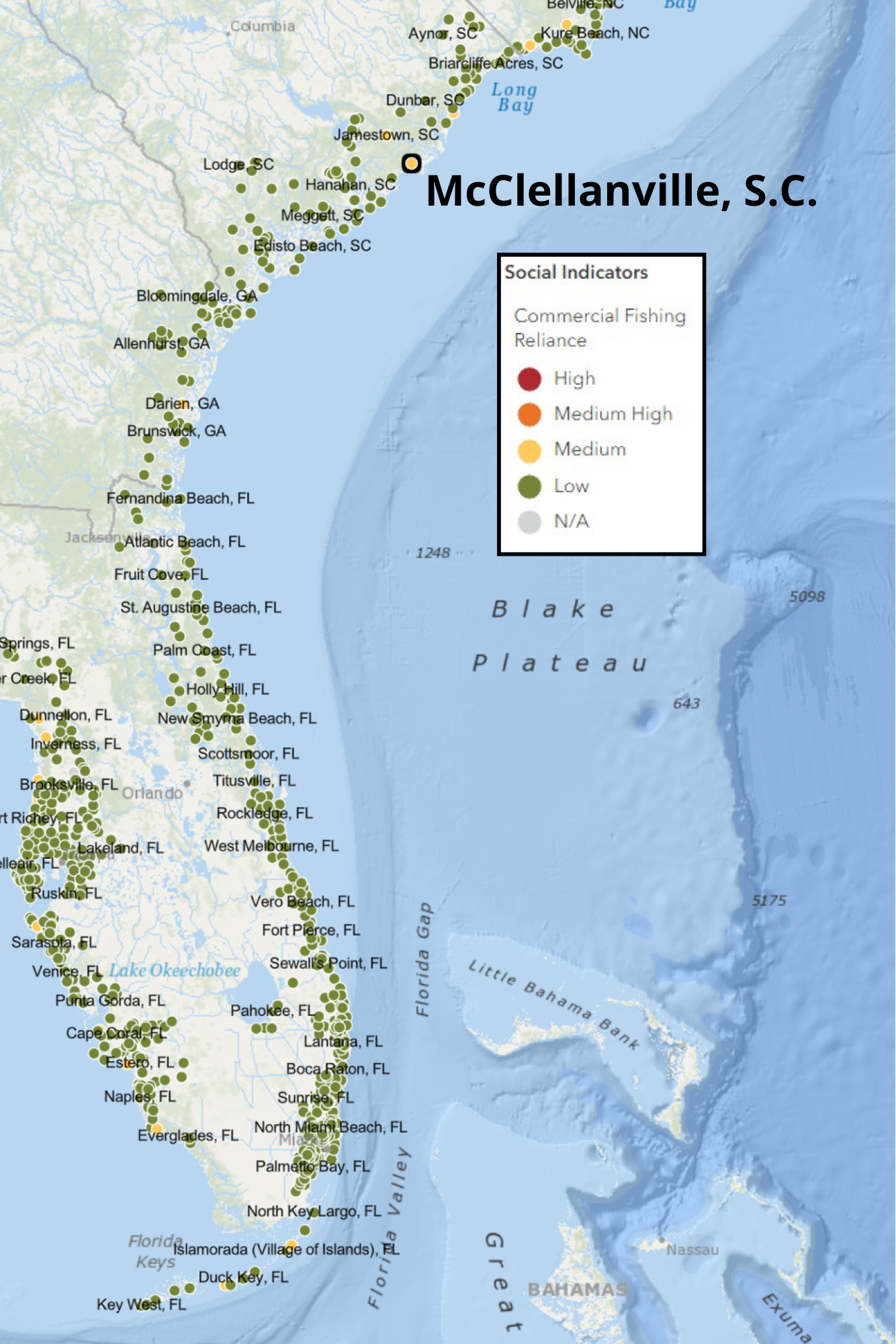

As one of the dwindling number of working waterfronts responsible for the booming seafood industry in South Carolina, McClellanville has deep-running ties to the sea, dating back to its settlement by French-Huguenots in 1685. Today, McClellanville is a small fishing town economically sustained by the commercial harvest of approximately 47 species. According to the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service’s Social Indicators for Coastal Communities Tool, McClellanville is more reliant on commercial fishing than most communities within the geographic region of Wilmington, N.C., to Key West, Fla., also known as the South Atlantic Bight. Not only does the town need commercial fishing to sustain itself, but the region needs McClellanville to continue to serve as a seafood hub.

Watermen are pillars of the McClellanville community, involved at every level, from town council members and local historians to volunteers at events like the annual Shrimp Festival. The Consortium has worked with the Town of McClellanville since 2016 on the “Preserving McClellanville’s Working Waterfront Initiative.” The initiative led to the creation of the MWA, which acts as a steward of maritime industries. The initiative also identified key needs for the long-term sustainability of its working waterfront, including a model for training the next generation of commercial fishers. Here’s where the South Carolina Commercial Seafood Apprenticeship Program comes in, and it’s just in time.

“Across the board, people in the commercial fishing industry are worried about the future,” says the Consortium’s Commercial Seafood Apprenticeship Program Coordinator Angela Treptow. “It’s getting harder and harder to find qualified, reliable people who want to work in the industry, especially young people.”

This phenomenon, called the “Graying of the Fleet,” is not just a concern in South Carolina. Alaska Sea Grant researcher Courtney Carothers found that “the average age of fishermen in Alaska’s fisheries has increased by ten years over the past generation, and overall, rural communities have lost 30 percent of their local permit holders.” Similar trends have arced across the U.S., causing concern everywhere from Maine to Fla. Possible barriers include high financial costs, as permits, gear, vessel(s), and training time add up. Fishers must meet physical requirements; they regularly haul loads over 50 pounds, operate heavy machinery, and work odd hours in various weather conditions. Social elements have an impact, too. Watermen rely on crewmates for their livelihoods and, at times, their lives. Developing trust within this industry requires a willingness to learn and a positive but realistic outlook toward hard work.

Thankfully, learning the ropes comes with high reward. Experienced fishers move through economic turns by innovating marketing strategies, integrating new technologies, shortening supply chains, developing community partnerships, and following consumer trends. Mark Marhefka, owner and operator of Abundant Seafood based in nearby Mount Pleasant, S.C., recognized back in 2009 that a community-supported fishery could cut out the middleman and deliver seafood directly to local members, just as the “Eat Local” movement was on the rise. Today, Abundant Seafood is a cornerstone for local foodies, families, and chefs who love knowing the people behind the dish and want to be first in line for fresh seafood. Demand for local seafood is only growing. It’s time for the next generation of entrepreneurs to tap into the wealth of maritime knowledge in our working waterfronts before the average fisherman retires.

With the stakes increasing each year, communities like Point Judith, R.I., have implemented apprenticeships to lure in a new workforce and revitalize the fleet by addressing barriers to entry. The Consortium developed CSAP with the successes and lessons of the Rhode Island Commercial Fishing Apprenticeship in mind, recognizing the necessity of providing stipends, housing, and career connections to meet the needs of both the commercial fishing community and the recruits.

“I think this program is going to help the next generation see commercial fishing and mariculture farming as a viable career opportunity,” says Angela Treptow, “it will also help us identify reliable, vetted employees for industry members who are looking for people to join their business.”

Local watermen have shown tremendous support for the program, participating as instructors, program advisors, and mentors. Pete Kornack of Cape Romain Oyster Cooperative served in each of these roles and says CSAP “Will have a huge impact on commercial fishing for the entire region. It is wonderful to see this level of cooperation between local, state, and federal government and the local fishing community.”

Today, we reap the benefits of these collaborations. Captain Jeff Spahr throws anchor on a bank of salt marsh between Muddy Bay and Cape Romain Harbor, where Spartina grows past our heads. At low tide, the mud flats are accessible, and oysters bare themselves like jagged teeth under the midday sun. We are all thankful for our thick-soled rubber boots. Spahr instructs us to find densely layered shell beds to prevent our feet from sinking, potentially trapping us foot- or knee-deep in silt or “pluff mud.” Armed with inflatable personal flotation devices, waders, and cut-proof gloves, we cautiously maneuver through thick, pluff mud. Wild oyster season runs from October to May, so we are harvesting the last growth before summer temperatures encourage the production of gametes, harkening reproduction for these diploid bivalves.

Captain Spahr demonstrates how to select and prepare individual oysters for purchase by restaurants and markets. With a cluster of wild oysters in one hand and a crowbar in the other, Spahr splits away external bivalves until the largest oyster sits alone in his palm, ready for a rinse before serving on the half-shell. This process is called “culling in place.” It ensures that smaller oysters and dead shells return to their native shoreline to continue growing or serving as substrate, or foundation, for future generations of oysters.

The apprentices navigate the bank armed with plastic crates and crowbars, collecting bushels of oysters. We try our hand at selecting and preparing singles. Spahr roves around to check on our progress, often nodding appreciatively at what he calls a “Chef’s Select,” a large oyster single with small oysters, called spat, attached to its shell. The work is lighthearted, but as the sun beats down, we stop often to rehydrate. With each passing minute, more oysters are revealed as the tide recedes.

Once filled, Jack and Jeff Spahr tag each bushel in accordance with the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC) and the S.C. Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR), indicating when and where these oysters were harvested. Due to the potential of illness from consuming raw shellfish, all shellfish products must have thorough documentation. In South Carolina, commercial oystermen have 18 hours post-harvest until raw oysters must be cooled to an internal temperature of 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Illegally harvested or improperly handled shellfish can result in heavy fines, seizure of product and equipment, or incarceration. Luckily, we are in expert hands with Jeff Spahr, who has perfected his timing.

“You get into a rhythm,” Jeff Spahr says after an hour or so on the reef, joking that he usually listens to podcasts while he’s collecting. Spahr has carefully maintained this culture ground, as one of only 115 culture permit-holders in the state, to cultivate some of South Carolina’s finest Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica), renowned for a bouncy texture and briny flavor. Spahr encourages the oyster lovers among us to taste for ourselves. We harvest, rinse, crack, and slurp live oysters off the cold half-shell.

Could anything be better?

Captain Spahr inspects bushels as we load up the skiffs, answering any lingering questions. Next is a lesson on oyster preparation using a shellfish tumbler of Spahr’s design. A tumbler is a metal chute with holes that washes oysters, sorts them by size, and smooths sharp edges, or “blades.” Smaller, slower-growing oysters are separated from ready-to-eat oysters, bagged up, and returned to the creek for further development.

For our apprentices, the next two weeks are a stream of lessons including clamming, shrimping, crabbing and two days on a long-haul at sea. The tried-and-true way to develop a workforce in the challenging but rewarding field of commercial seafood is the simplest – get the right people on the water at the right time with the right gear, and let the experience speak for itself.

Southeastern residents interested in the commercial seafood industry should consider an apprenticeship program. Funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Sea Grant Office and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Rural Business Development Grant Program, the South Carolina Commercial Seafood Apprenticeship Program covers room and board and includes a $1000 stipend for each graduate following completion. Participants receive a CPR, First Aid, and automated external defibrillator certification, a U.S. Coast Guard Drill Conductor certification, and a certificate of completion from the S.C. Sea Grant Consortium. CSAP 2025 will be held from May 5 to May 30. Sign up to be included on a mailing list to receive application materials as soon as the application period is open for 2025. To learn more, visit the CSAP webpage.

CSAP’s graduating class of 2024, from left to right: Patricia Ann Cope, Bekah Bennett, Garret Kestory, Jocelyn Juliano (Living Marine Resources Program Specialist), Angela Treptow (Commercial Seafood Apprenticeship Program Coordinator), Blake Godsey and Shane Brackett. Photo by Hailey Murphy.