Tuna researcher Molly Lutcavage has been working with fishermen for over two decades. “We were criticized for working with commercial fishermen. But how could you not work with commercial fishermen? They're the experts,” she says. A veteran tuna researcher, Lutcavage is helping a team of fishermen and scientists in Hawaii to employ new tagging technology for ahi (yellowfin) tuna.

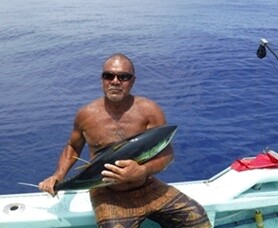

Nathan Abe, who fishes for ahi and other tuna species in the waters west of the Hawaii’s Big Island has been tagging the ahi tuna with a new HI tag, a small strip of plastic bearing an RFID chip. Developed by Tim Lam and Lutcavage, the HI tag in combination with a smartphone app will help fishermen and scientists learn more about the travels of the ahi tuna.

When fishermen bring a tuna alongside, they can attach the tags just behind the dorsal fin using an applicator similar to an awl. When a tagged fish is caught again and a fisherman scans the tag with a smartphone, it transmits data, including the tag number and location, to a secure database in the cloud.

“A simple ID tag can only give you points in a fish’s journey: release, and recaptures- nothing in between,” says Lutcavage. “A data logger satellite tag can only tell you what the fish did while it carried the tag- not what happens before or after the tag pops off. What we’d all like to have is a lifetime track of these long-lived ocean voyagers.” Lutcavage notes that they are testing the Beta version of the technology, and that she hopes to bring it to U.S. bluefin tuna fishermen on the East Coast.

Each HI Tags costs an estimated $5, far cheaper than the $4,000 dollar pop-up tags Lam and Lutcavage previously used to demonstrate that ahi sometimes travel great distances around the Pacific.

What Abe wants to know, though, is not how far the ahi travel, but whether there is a local stock that stays in the mid-Pacific near Hawaii. “I wonder if the fish are as migratory as the scientists think,” he says. “I think we have a local population. We’re out here in the middle of the Pacific with nothing around us but deep water. And there’s guys here that can hit yellowfin year-round.” Abe notes that there are many ways to fish tuna, but one way he uses is to drop a bag of palo (chum) and a baited hook down to 100 fathoms and release the chum. “They come and eat the chum and then hopefully bite the hook,” he says. “But they’re smart and they don’t always bite, so we’re feeding them, and we watch them grow from 25 to 70 pounds over the course of a year.”

Abe hopes that the tagging will prove his theory, but he’ll trust the science he’s a part of. “If we tag one here in Kona, and they catch it later in Kawaii, that could mean they’re staying here,” he says, noting that this idea could have management implications. “If the tagging shows there’s no fish, throw that on the table. I’ll accept that.”