Fisheries regulators voted this month to “discontinue” development of a plan to reopen the Northern Edge of Georges Bank — a lucrative scallop ground that has long been closed to commercial fishing.

In April, the New England Fishery Management Council agreed to consider requests to reopen the fishing grounds at the urging of both the scallop industry and Mayor Jon Mitchell. He and industry representatives cited significant headwinds for the region’s top fishery, including a slump in prices and fewer days at sea for fishermen. They added that opening the Northern Edge would benefit the whole port economy and surrounding businesses.

But in the midst of a four-day meeting in Freeport, Maine, the Council voted not to continue discussing plans to reopen the area in order to focus on the “long-term productivity of the Georges Bank scallop resource.” For regulators, it’s a balancing act to weigh sustainability and the economic pressures on fishermen to sustain their livelihoods.

“We know there is a high density of scallops there. But you need those dense aggregations to have spawning success in the future,” said Jonathon Peros, who is the Council’s lead fishery analyst for sea scallops. He explained that scallops spawning in the region act as a seed source to other active scalloping grounds.

The motion to discontinue was made by Geoff Smith, a council member who is also the marine program director for The Nature Conservancy in Maine.

“It’s a tough year for groundfish, herring, lobster and scallops. Opening up the Northern Edge could have long-term negative impacts on all of those resources,” Smith said. “The council carefully considered the tradeoffs and decided on maintaining those protections for the long-term benefit of all the fisheries out there on Georges Bank.”

The council’s decision dashed the hopes of fishermen, industry representatives and city officials, all of whom were eager to gain more access to prime fishing grounds with a challenging few years on the horizon.

“Halting work on the Northern Edge so abruptly is an affront to scallop fishermen who were given every reason to believe that the council was working toward a fair, long-term solution,” Mayor Mitchell wrote in a statement early this month.

Only three out of 17 council members voted to continue the discussions to reopen the area.

“As a member of the scallop industry, I am disappointed,” said Eric Hansen, who is a member of the council and the owner of two New Bedford scallop boats. “There is a lot of resource (scallops) that has been wasted there. They were not harvested, they were not revenue for the scallop industry and were not food for the country. They are dying of old age.”

The council’s decision came less than three months after it voted to advance the opening of Northern Edge. In his statement, Mayor Mitchell chided the council for giving “scant public notice” and backpedaling on data that shows “scallops are abundant in the area.”

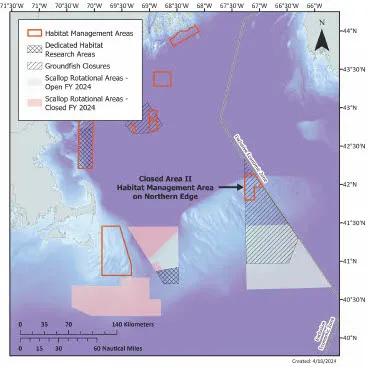

The Northern Edge is the northernmost portion of the broad and productive fishing grounds called Georges Bank. In 1994, the area was closed to commercial fishing to protect habitat for spawning cod and other bottom dwelling fisheries. At the meeting in April, industry reps highlighted an irony: since the closure over 30 years ago, groundfish populations have continued to decline while the area has remained locked up to scallopers.

“In those 30 years of closure, several cohorts of scallops, worth 100s of millions of dollars have come and gone,” Drew Minkiewicz, an attorney for the Sustainable Scallop Fund, wrote to the council. “It’s faith based management,” he added.

The scallop industry is regulated under a rotational system of management. Regulators, scientists and industry leaders routinely open and close certain areas to fishing to encourage population growth while concentrating fishing efforts in other areas.

In recent years, they said, scallop populations in the areas currently open to fishing have reached the end of their cycle. Domestic landings have declined from 60 million pounds in 2019 to about 30 million pounds in 2022. Meanwhile, scallop populations in the Northern Edge have boomed, growing from an estimated 11 million pounds in 2017 to 27 million pounds last year, according to a combination of government surveys presented in April.

However, council members made clear in their rationale that even though the Northern Edge is flush with scallops, jeopardizing the spawning habitat could cause a downward spiral for the industry.

“Allowing access to the Northern Edge Area could undermine long-term attainment of optimum yield in the scallop fishery because the large, high density scallop aggregations on the Northern Edge are likely an important larval source for scallop beds,” the council wrote.

Mayor Mitchell and the scallop industry have pressed the council to consider opening up the Northern Edge to scalloping for over a decade. It has been shot down in the past due to concern that scalloping and other fishing activity that involved dragging gear across the ocean floor would disturb the spawning habitats for both groundfish and scallops.

Hansen said that though discussions of reopening the Northern Edge could continue in the future, council members were told that the council’s staff has a full agenda for the next few years and will not have time to reconsider the topic.

“This was the only window,” Hansen said. “I understand the vote, but I don’t agree with it.”

Article courtesy of Will Sennott and The New Bedford Light. Read more here.