If you are around fishing for long enough, you start to see patterns — some good, some not so good. When I started working at NF 15 years ago, I had a background in maritime publishing, but not so much in fishing, fishing boats or fisheries. I had a lot to learn.

Then-editor Jerry Fraser put me to work on compiling the Fishing Back When page. I’d get lost in back issues for days. What I noticed right away was the patterns — primarily set by the seasons. Stories covered the starts and ends to fishing seasons around the same time every year.

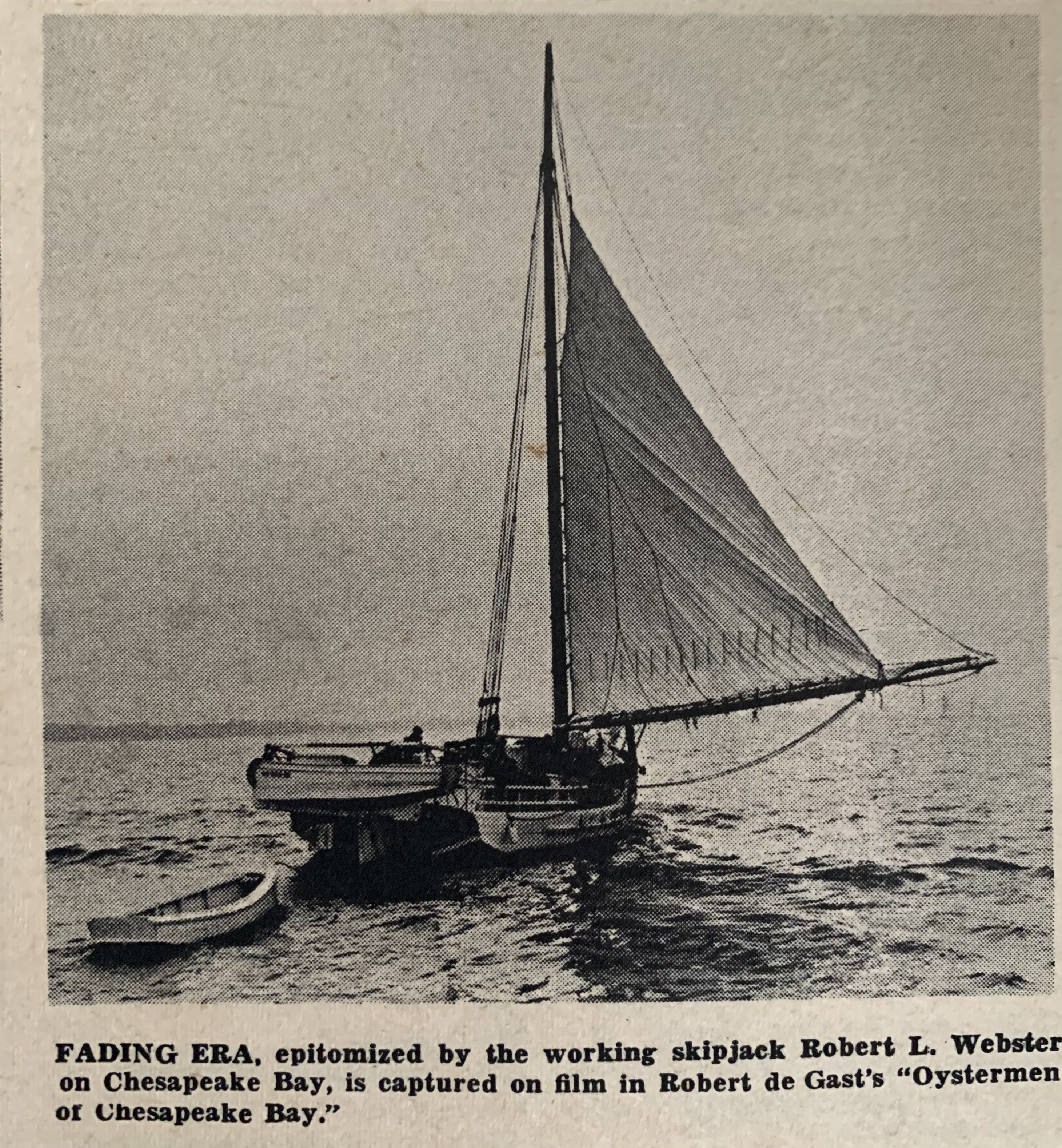

But my favorite were the serendipitous patterns. Now that I’m back to writing Fishing Back When, these are still my favorites. I happened to open the February 1971 issue to a page highlighting the life of Chesapeake Bay’s oystermen and their skipjacks under sail with the publication of Robert de Gast’s “The Oystermen of the Chesapeake.” The book is a collection of de Gast’s photography. He spent a year living and working with Maryland watermen, documenting their lives with 6,000 photos (back when the art of photography was an investment of time, equipment, processing and paper).

This issue happens to jump forward 50 years with another profile on a Maryland oyster crew. And like it goes in fishing, some things have changed, but many have stayed the same — including most of the crew in Boats & Gear Editor Paul Molyneaux’s story.

Stoney Whitelock’s crew on the Minnie V. is mostly comprised of Maryland watermen who have been plying these waters in wooden deadrise boats going on 70 years, Whitelock included.

They are still out there, their wooden deadrise boats are still running under sail (and sometimes power), but the fishery has changed significantly to overcome the challenges of habitat degradation, parasites and disease.

De Gast’s book covers a year in the life, while Paul’s feature profiles a workday at sea with these hardworking watermen, who have kept at it, despite decades of challenges, because they love it.

As they say, fishing ain’t catching. If that’s what you’re in it for, you’re in the wrong job. Those days can be some of the best days. But you have to be in it for every day, good and bad, to call yourself a fisherman. And when you’ve logged as many hours as Stoney Whitelock and his crew, you get to call yourself whatever you like.

The caption for one of de Gast’s photos (at the top of the page) of the working skipjack Robert L. Webster calls this fishery and the boats that ply its waters a “fading era.” Little did they know then that the perseverance of the Chesapeake baymen should not be so easily discounted.