The wealth of a fishery is not only in the sea but in the knowledge base of the communities that rely on those fisheries. On October 22 and 23rd of 2024, the transboundary Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) Nation hosted its second Summit of the Bay, a two-day convocation of fishermen, scientists, fishery managers, and tribal leaders to discuss the troubles of the Passamaquoddy Bay and how to rectify them.

What transpired in two days was a rare convergence of political, spiritual, and scientific knowledge—community wealth. The Summit opened the door for networking across fields, beliefs, and borders. Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Nation in New Brunswick, Canada organized the first Summit by himself in March of 2022. This time, he had a team and a great location at the Huntsman Marine Aquarium in the beautiful town of St. Andrews, New Brunswick, with views of Maine across the bay.

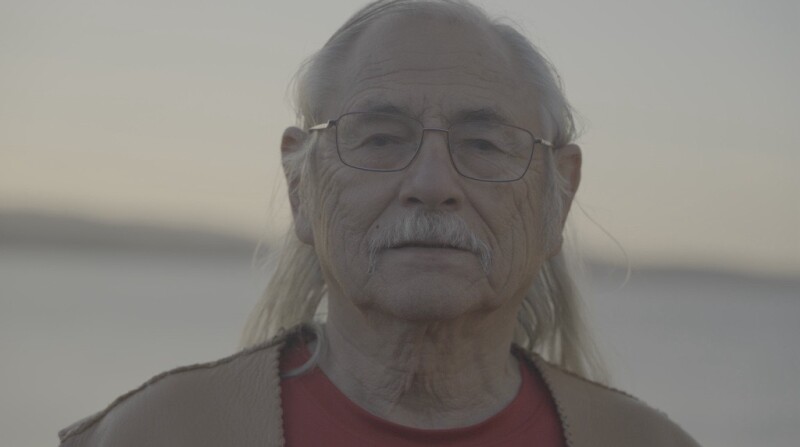

The Summit of the Bay II agenda included everything from ceremonies and the opening Shared Visualizing Our Shared Journey presentation to presentations by the region’s fishermen and tribal members telling stories of how the Passamaquoddy Cobscook Bay systems, which once teemed with herring, groundfish, and salmon, have changed over the years. “It’s easy to see what happened,” says Eric Altvater, a former chief of the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Sipayik, on the US side of the boundary. “In 1969 there were 17 canneries working round the clock in Eastport, Maine. In September of that year they canned over 14 million pounds of herring. Where’d the herring go? They went into cans.”

So went the cod, pollock, and haddock—all gone now. To find the way back, the scientists, economists, social scientists, discussed ways to connect their respective research with Tribal and community values, and co-management.

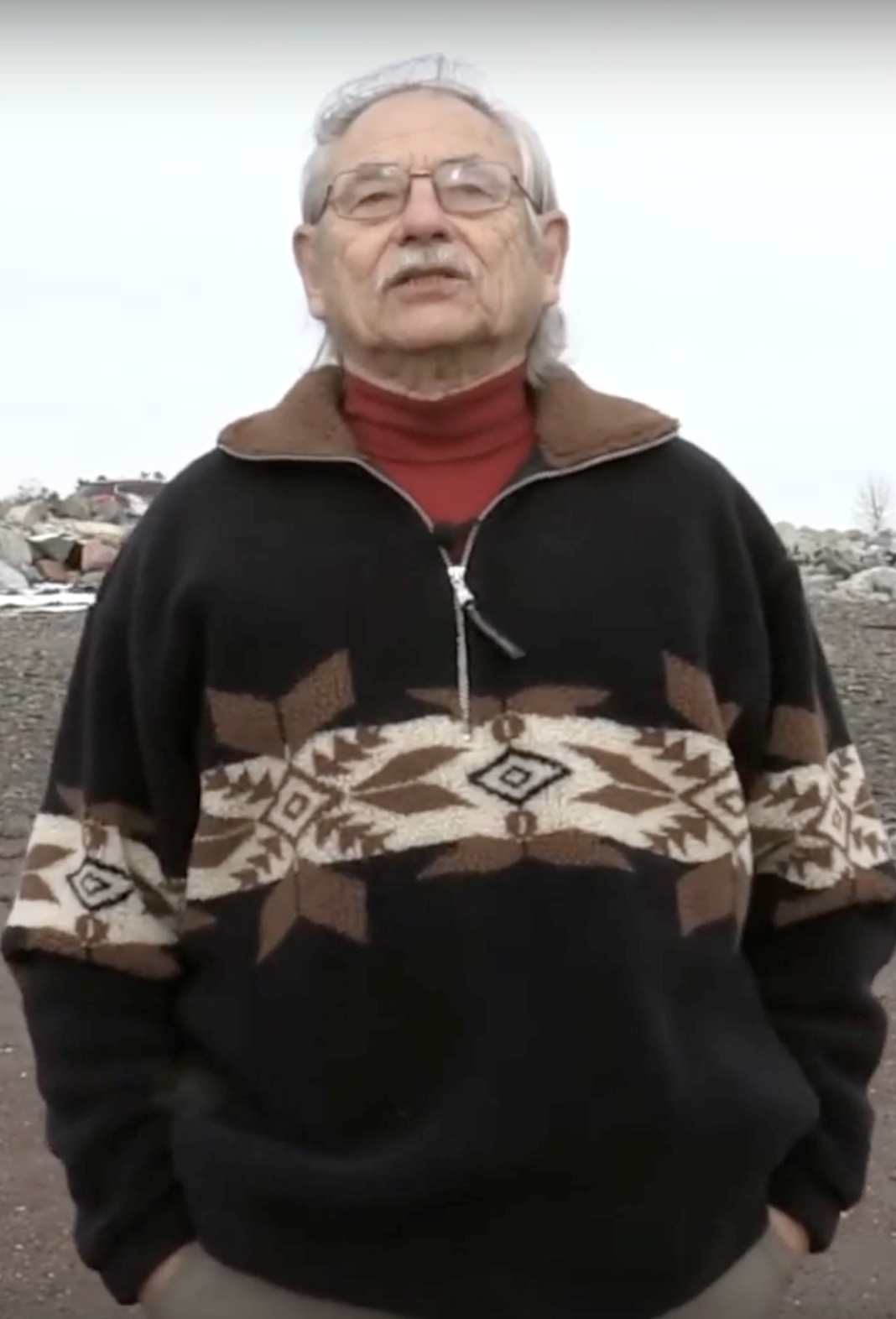

Rob Steveson, a biologist with Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, believes it is entirely possible to create a holistic management regime that restores the bay system and puts control in local hands. “We can talk about foresighting,” said Stevenson. “That is, when we look at the future, we can determine what is possible, what is plausible, and what is probable. But what is probable may not be preferable.”

Stevenson explained that the people in charge can make decisions that increase the likelihood of preferable outcomes looking years and decades into the future, noting that the opportunity to do that is now.

Many speakers pointed out that the 1760 Treaty of Peace and Friendship had guaranteed Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy Tribes the right to hunt, fish, gather, and earn a reasonable living without British interference. While the treaty transferred to Canada and the United States, the trouble for the two remaining members of the Peskotomuhkati Nation in New Brunswick is that they have yet to be recognized by the Canadian government, and the Passamaquoddy from Sipayik on the US side of the border, have been cited for violations when fishing in their traditional waters on the Canadian side of the line.

But the show of mutual cooperation at the summit offered hope for a revival of the bay and a resolving of issues. “I have never seen this,” said Passamaquoddy elder Dolly Apt waving her hand at the crowded Huntsman auditorium. “Natives and newcomers working together like this.”