Of the various alternative fuels, LNG and hydrogen offer promise but with some risks

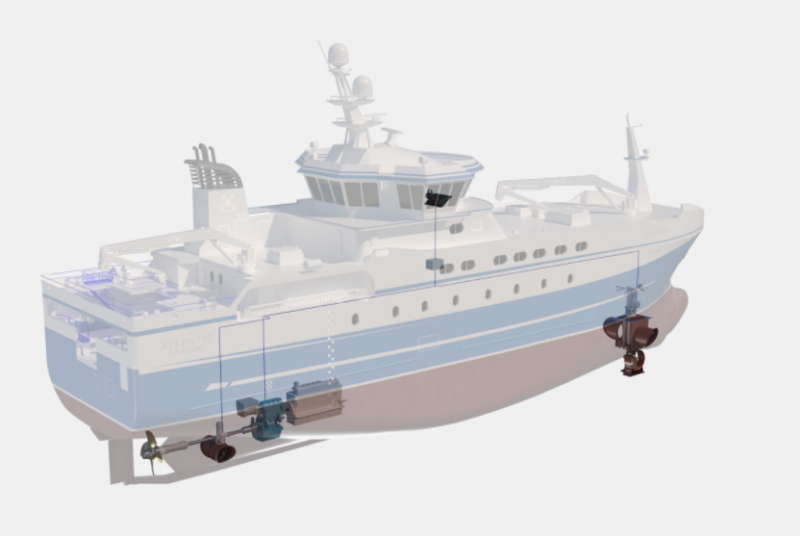

Naval architects and engineers at the Norwegian company Skipsteknisk designed what may be the first hydrogen-powered fishing vessel, the 70-meter Norwegian longliner, Loran. While the vessel will still have conventional diesel engines, it will also have two 185-kW hydrogen fuel cells and a 2,000-kWh battery bank.

“The battery is a kind of buffer in the system,” says Skipteknisk’s sales manager for fishing vessels, Inge Bertil Straume. “The battery stores energy from charging stations at the pier, the hydrogen cells or the diesel engines. It’s hybrid thinking. You have a number of sources, because we are still a decade away from carbon neutral.”

While the engineering is doable, according to Bertil Straume, there remain many unknowns in the use of hydrogen, including sustainability and storage.

“We are the pioneers,” he says. “We haven’t even cut the steel yet for this vessel.”

The Loran will have diesel and electric motor options in the gearing for the main propeller.

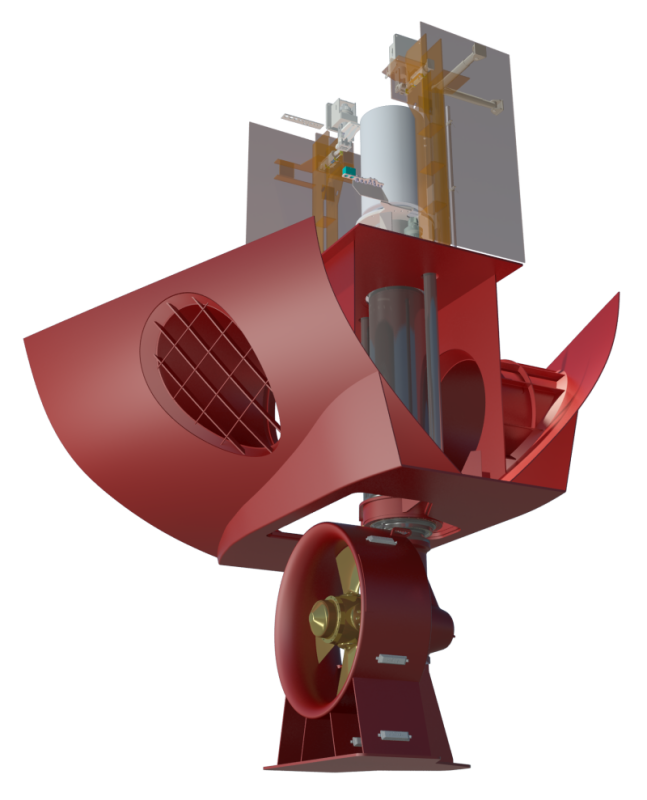

“It will also have a retractable propeller for when they are hauling the longline, and for redundancy, in case something ever happened to the main,” says Straume. “Longliners are kind of the nomads of the sea. They are often far away from the fleet.” The retractable propeller on the Loran is an electric-drive bow thruster that can be lowered into the water and used as an azimuth propeller.

The real challenge with hydrogen, Bertil Straume notes, is with sustainable generation and storage onboard.

“The hydrogen system is all above deck,” he says. “We don’t have any safety standards yet for putting a this below deck.” According to Straume, the hydrogen will be stored in gas form at 5,000 psi in 10 20-foot tanks aft of the wheelhouse, with the fuel cells close by.

“We also need a way to generate the hydrogen that is cost effective,” he says. “Right now, if you use 1,000 kW to produce hydrogen by electrolysis, you get 250 kW of hydrogen. No fisherman can make money buying fuel on a 4-to-1 ratio. And when you lose 50 percent of that energy going to the motor, so in the end you get 125 kW for your 1,000 kW.”

The Loran project is subsidized by the Norwegian government and other investors. Enova, an agency of the Norwegian Ministry of Climate and the Environment, put over $10 million into the project. The hydrogen auxiliary power is expected to reduce fossil fuel use by 40 percent and is seen as a step toward a zero emissions future.

According to the Ministry of Climate and Environment, Norway plans to cut emissions from shipping by 50 percent before 2030. The International Maritime Organization is calling for a 50 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions — compared to 2008 levels — by 2050. But as Straume reiterates, functional hydrogen power may still be a decade out. Nonetheless, the investors remain optimistic.

“By being the first out with hydrogen, we hope that the new Loran will be one of the vessels that form the basis for a green shift in fishing,” Ståle Otto Dyb, captain of the Loran, says in a story on fiskerforum.

Skipsteknisk has also designed and LNG fueled purse seiner, the Selvåg Senior, with a 6,400-hp Wärtsilä 8V31DF medium speed engine, and a Cummins QSK60 powered genset that will run on regular diesel and be fitted with IMO tier 3 SCR aftertreatment.

“The 31DF is in the Guinness book of world records as the most efficient engine in existence,” says Cato Esperø, head of sales at Wärtsilä. “The DF stands for Dual Fuel. It can run on diesel or LNG and diesel.” According to Esperø, the mix of LNG and diesel is delivered through different supply lines to a single injector per cylinder. “In case you run out of LNG, you can run on just diesel,” he says. “To run on just LNG, though, you would still need a pilot fuel of at least 1 percent diesel, or a spark.”

Again, as with hydrogen, storage is an issue, but standards exist. And at least two LNG-powered fishing vessels are in operation.

“If you look at the density,” says Esperø. “LNG is not as dense as diesel, and it needs to be stored at minus 173 degrees Celsius. It requires cryonical tanks, which are round. So, you have all that room around them.” Esperø estimates off the cuff that LNG would require twice the storage space for the same amount of power.

The upside of both hydrogen and LNG fuels is in the exhaust. Hydrogen exhaust is nothing but water and heat, and LNG burns clean.

“The 31DF does not need aftertreatment,” says Esperø. “There is no NOX or SOX in the exhaust, and CO2 is reduced by 20 percent.”

The technology has a long way to go but is part of the plan to make the world’s fishing fleets carbon neutral.