Alaska pollock is one of the world’s most valuable fisheries, due to the enormous annual harvest volume and the versatility of the white, mild-flavored fish, federal economists say.

Fairly or unfairly, the pollock fishery’s prodigious size makes it an easy target on controversial issues such as salmon bycatch.

Lately, another criticism has taken on a higher profile – the charge that the pollock industry’s pelagic nets aren’t really “midwater” gear, but rather touch bottom much of the time, damaging seafloor habitat and mangling king and Tanner crab. These crab fisheries have seen total closures in recent years due to stock declines primarily attributed to changes in the marine environment.

To address the bottom contact issue, the pollock industry is embarking on an ambitious project to gain a better understanding of how its trawl gear works in the water and, possibly, to develop improved designs.

The effort is called the Gear Innovation Initiative, and it involves an unusual collaboration between the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska pollock fleets.

It also involves a lot of trust among vessel owners and captains when it comes to sharing information and buying into the goals of the initiative.

Alaska’s pollock fishery is divided into two major zones – the Eastern Bering Sea, which has a total allowable catch (TAC) this year of 1,375,000 metric tons of pollock, and the Gulf of Alaska, with a TAC of 186,245 tons. Trawl vessels generally are bigger and more powerful in the Bering Sea. Bottom conditions are different in the two zones – generally sandy or muddy in the Bering and rocky, volcanic and trenched in the Gulf.

A total of 114 catcher vessels targeted pollock with pelagic gear last year in the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska, with an additional 13 catcher-processors operating in the Bering, according to federal officials.

A big part of the initiative is cataloging gear – collecting detailed descriptions of each boat’s trawls. With this information, estimates of benthic habitat disturbance by pelagic trawl gear can be more accurately reflected through modeling, a project description says.

“This is going to be a true scientific study to really catalog the gear and how it performs,” said Doug Christensen, president and CEO of Seattle-based Arctic Storm Management Group. The company operates two Bering Sea pollock catcher-processors participating in the initiative – the 334-foot Arctic Storm and the newly built 326-foot Arctic Fjord.

An initial step was persuading a core group of vessel operators to share their net designs as part of the initiative, Christensen said. Trawlers differ in terms of horsepower, vessel length and how the gear moves through the water. They use trawls from different makers, and captains tweak their gear.

Julie Bonney, executive director of the Kodiak-based Alaska Groundfish Data Bank, said the Gulf of Alaska fleet has bought into the initiative, with about 50 vessels providing their gear inventory.

“I don’t think people are scared where this will take us,” she said. “We don’t really know enough about how our gear functions. Learning more will allow us to defend our fisheries and make improvements as necessary. This is a big undertaking for the pollock fleet – collecting gear inventories for the boats, interviewing all the captains about how they fish their gear, modeling how the gear fishes, conducting costly field testing and, finally, determining next steps.”

Jon Kurland, Alaska regional administrator for the National Marine Fisheries Service, agreed the issue of pollock trawl gear contacting the seafloor has been gaining attention.

The Gear Innovation Initiative, he said, is “a worthwhile effort to catalog and characterize the different types of pelagic trawls and improve understanding of the amount of bottom contact. That should be a useful baseline.”

Playing a key role in the initiative is Brad Harris, director of the Fisheries, Aquatic Science and Technology Laboratory at Alaska Pacific University. He’s studied fishing gears and their impact on habitat in several U.S. fisheries and worked on projects in New Zealand and Northern Ireland.

“After decades of outstanding fisheries science in the North Pacific, it’s surprising how little has been done to understand fishing gear, so we’re building a foundation,” he said. Harris currently works on the key model the North Pacific and the New England fishery management councils use to evaluate fishing effects on essential fish habitat.

“Adult pollock spend a lot of time on or very near the seabed, and the North Pacific Council’s habitat assessments, as far back as 2010, all assume pollock trawls are making contact with the bottom. The goal here is to reduce the uncertainty about when, where and how much,” Harris said.

In addition to informing fishery management, he said, the gear initiative also should prove beneficial to the fleet as well, including the potential to reduce bycatch and improve fuel efficiency.

The initiative involves cataloging net plans and specifications for every pollock trawl in Bering and Gulf federal fisheries. Next, the trawl geometry (shape) and points of potential seafloor contact will be examined using computer models and likely flume tank scale models of the gears. Then comes field testing at sea, and ultimately gear modification or new designs. The initiative schedule runs through 2026.

It’s a multimillion-dollar project. The field testing will be especially costly for the fleet, with expenses plus fishery displacement time.

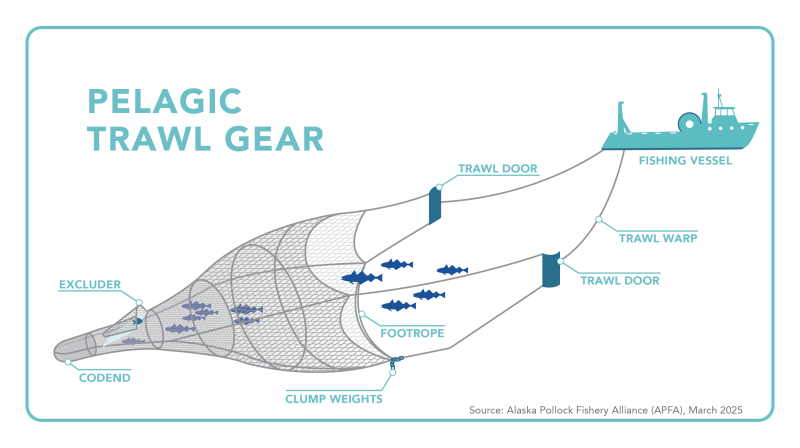

Figuring out the extent to which parts of a pelagic trawl – the footrope, clump weights – might be contacting the bottom isn’t as easy as it might seem. Cameras used on some trawls offer only limited visibility in turbid water.

Seafloor contact could be reduced by lifting pollock gear higher off the bottom. But this would risk sending the trawl into spaces where salmon bycatch could become a bigger problem.

Tilt sensors mounted on trawl gear are one research tool offering promise for better quantifying bottom contact. The sensors Harris and his team designed attach to the trawl footrope.

Ben Enticknap is with the conservation group Oceana, which is suing the National Marine Fisheries Service alleging the agency has failed to protect fragile seafloor habitats. He believes public attention on habitat protection and bycatch is at “an all-time high.”

“For so long, the pollock industry has been able to get by on the idea that ‘we’re pelagic.’ They’re more often on the bottom than they’re not,” Enticknap said.

Oceana’s lawsuit states: “Although pelagic, or midwater, trawls are not considered bottom trawls, new information shows that pelagic trawls are in contact with the seafloor between 40 and 100 percent of the time.”

While Oceana isn’t working with the pollock industry on its Gear Innovation Initiative, Enticknap said “we wish them great success” in finding ways to advance habitat conservation.

Arctic Storm’s Christensen said that with his vessels trawling largely in mud and sand, required ecosystem reviews consistently determine gear impacts are not significant.

Ben Ley, an owner in the 58-foot combination boat Cape St. Elias fishing out of King Cove, Alaska, has a strong interest in the Gear Innovation Initiative. Which seems natural for a fisherman with an electrical engineering degree. The goal of the initiative, he said, is to “really improve our knowledge of how our gear works.”

“As a combination boat, we fish for salmon, cod, pollock, black cod, and crab. We are committed to science-based fishing practices,” Ley said.

He’s turned over all the specifications on his trawl gear, which includes two designs – one from Swan Net USA, the other from Icelandic company Hampidjan.

It’s a big commitment Ley and others in Alaska’s pollock fishery are making on a project that could prove instrumental in demonstrating the industry’s sustainability.