The National Transportation Safety Board held a public meeting Tuesday, June 29, to determine the likely causes of the F/V Scandies Rose sinking on Dec. 31, 2019.

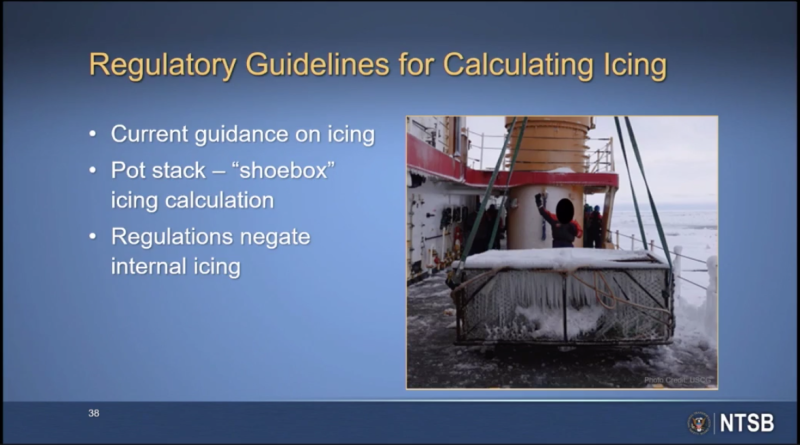

In the meeting, board members repeatedly called out the vessel’s flawed stability instructions as well as systemic failures in weather prediction and icing calculations for the gear on deck.

The 130-foot commercial fishing boat and its seven crew members had left Kodiak, Alaska, on Dec. 30, 2019, to drop pots for the federal pot-cod fishery, followed by the opilio crab season.

Five of the seven crew members were presumed lost but not recovered. Two survivors testified during the two-week U.S. Coast Guard hearings in February and March 2021, in which the NTSB participated in order to make its determinations for this report.

Scandies Rose Hearings In-Depth

The stability instructions for the Scandies Rose were determined to have failed to include downflooding points on the vessel, and that they provided inaccurate descriptions of parts of the deck space.

One of the standout observations in the overview and questions during the board meeting was that icing conditions worsened in the area of Sutwik Island, where Captain Gary Cobban Jr. was headed in an attempt to seek refuge from observed sea conditions and accumulating ice in open waters.

Although the weather conditions at the nearby weather stations were accurate, they did not accurately predict the conditions observed in the area of the sinking.

One possible solution, said NTSB Meteorology Group Chairman Paul Suffern, is an experimental NOAA website that more accurately predicts freezing spray accumulations.

“None of the captains of the fishing vessels in the area interviewed at the Marine Board of Investigation public hearing were aware of the National Weather Service Ocean Prediction Center Freezing Spray website,” Suffern noted. “And [they] agreed that the graphical freezing spray information would be a useful resource when operating in areas where freezing spray was present.”

The combination of a flawed stability report, inadequate international standards for estimating ice accumulation on pot gear, and the unpredicted heavy spray conditions in the area of Sutwik Island culminated in a catastrophic scenario for the Scandies Rose, the board determined.

“The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the capsizing and sinking of the commercial fishing vessel Scandies Rose was the inaccurate stability instructions of the vessel,” said Brian Curtis, director of the NTSB Office of Marine Safety. “It resulted in a low margin of stability to resist capsizing, combined with heavy asymmetric ice accumulation on the vessel due to localized wind and sea conditions that were more extreme than forecasted during the accident voyage.”

Excluded from the board’s determination of contributing factors in the vessel’s loss were:

• The captain’s decisions on loading and departure time

• Operational pressures

• Fatigue

• Drug or alcohol use

• Propulsion and steering systems

• Hull integrity

“The Scandies Rose did not capsize because the crew or the captain did not do their jobs, or because the vessel had been poorly maintained,” said Board Chairman Robert L. Sumwalt. “It sank because its captain only had partial access to the information that he needed to make the right decision. And the information that he did have was inaccurate.”

Recommendations — which are not binding — include:

• That the U.S. Coast Guard conduct a study to evaluate the effects of icing, including asymmetrical accumulation on crab pots and crab pot stacks; disseminate findings of the study to the industry; and establish regulatory calculations for fishing vessels to account for the effects of icing, including asymmetrical accumulation on a crab pot or pot stacks.

• That the Coast Guard revise Title 46 Code of Federal Regulations 28.530 to require that stability instructions include the icing amounts used to calculate stability criteria.

• That the Coast Guard develop an oversight program for stability instructions of commercial fishing vessels that are not required to develop a load line certificate, for accuracy and compliance with regulations.

• That the North Pacific Fishing Vessel Owners Association notify its fleet of the dangers of icing and flawed stability requirements.

• That NOAA make an experimental website that reports more detailed icing conditions and predictions fully operational and accessible for commercial use, and that the agency increase observational resources necessary for improved forecasts in the area.

• That the Coast Guard require the use of personal locator beacons for all personnel employed on vessels in the coastal, Great Lakes and ocean service to enhance their chances of survival.

• That the Coast Guard require all owners, masters, and chief engineers of commercial fishing industry vessels to receive training and demonstrate competency in vessel stability, watertight integrity, subdivision, and use of vessel stability information regardless of plans for implementing the other training provisions of the 2010 Coast Guard Authorization Act.

The last two recommendations to the Coast Guard were noted as having already been recommended and denied. All findings and recommendations were unanimously approved by the board.

“Regarding the final recommendation,” wrote the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association in a post on its site, “we will note that the 2010 Coast Guard Authorization Act requires that fishing vessel captains obtain hands-on training in vessel stability and hold a valid certificate issued under a course meeting the requirements of the 2010 Act. In the 11 years since the passage of the 2010 Act, the Coast Guard has yet to issue the regulations needed to enforce this requirement.”

AMSEA offers a U.S. Coast Guard-accepted Fishing Vessel Stability course. For more information, email the organization at coursecoord@amsea.org.

Following the 2015 loss of the cargo vessel El Faro, the NTSB recommended the use of PLBs on commercial vessels. The Coast Guard responded in 2018 that, at the time, PLBs did not provide the accuracy needed to pinpoint locations. The NTSB disagreed and reported in the meeting that the Coast Guard is reviewing its determination.

“Commercial fishing is one of the most dangerous occupations in the United States,” said Board Member Michael Graham. “Every year, more than 40 lives are lost. The Centers for Disease Control estimates a fatality rate of 35 times that all U.S. workers. For an industry that supports more than 700,000 jobs and contributes more than $50 billion to the economy, these workers deserve better. We must do more to protect those who have been risking their lives to feed all of us.”