From 2017 to 2019, fishing vessels switching off their identification devices obscured nearly 5 million hours of fishing activity. A new research displays intentional disabling of automatic identification system devices and reveals one of the disabling hotspots happens in U.S. waters off the coast of Alaska.

The new study, “Hotspots of Unseen Fishing Vessels”, was published Nov. 2 in the journal Science Advances and presents the first global dataset of AIS disabling in commercial fisheries, which obscures up to 6 percent of vessel activity. This work, which was supported by the Catena Foundation and NOAA’s Office of Law Enforcement, provides a global analysis that shows where fishing vessels’ identification devices have been switched off.

Lead author Heather Welch, a project scientist in the Institute of Marine Sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), worked on the study with researchers at Global Fishing Watch and NOAA Fisheries. While maintaining a dataset of vessel activity, Global Fishing Watch developed a machine learning method to distinguish intentional AIS disabling from gaps in satellite coverage and other technical issues, allowing Welch to identify the key reasons why the AIS devices were switched off.

Originally designed as a collision avoidance tool, the Automatic Identification System or AIS for short can be intentionally disabled—sometimes for legitimate reasons, and other times in an attempt to conceal illegal activities. That’s what this new research shows: the analysis harnesses automatic identification system, or AIS, data to provide information about global fishing activity, including illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

“AIS data can tell us a lot, but so can the lack of it,” said coauthor Tyler Clavelle, a data scientist at Global Fishing Watch. “We might not always be able to see what vessels are doing, but knowing when they’re intentionally hiding their movements provides valuable information that managers and scientists didn’t have before. Having a better understanding of where vessels may hide their position allows authorities to deploy valuable on-the-water resources more strategically, supporting improved fisheries management.”

Using the tools developed by Global Fishing Watch, which National Fisherman covered in an article last July - An interactive map to monitor the activity of dark fleets in coastal waters - Heather Welch, project scientist at UCSC and lead author, was able to identify four primary reasons for AIS disabling.

The team first developed a rule-based classification model to identify which gaps in AIS transmission are likely to be caused by intentional disabling, and reveal the locations, flag states, and gear types that have the most fishing vessel activity obscured by disabling.

Then they used a popular machine learning method called boosted regression trees to identify the primary drivers of suspected AIS disabling from a suite of potential drivers related to fishing ground quality, piracy, transshipment, and jurisdictional boundaries.

Four hotspots of unseen fishing vessels

Four hotspots of unseen fishing vessels

“There are some legitimate reasons why vessels disable their AIS, but we found two situations in which it is done for potentially nefarious reasons, either to fish in unauthorized locations or to obscure unauthorized transshipments,” said Heather Welch. “This dataset is now operationalized, and the data are produced in real time, so it can be used to target inspections and improve fisheries management.”

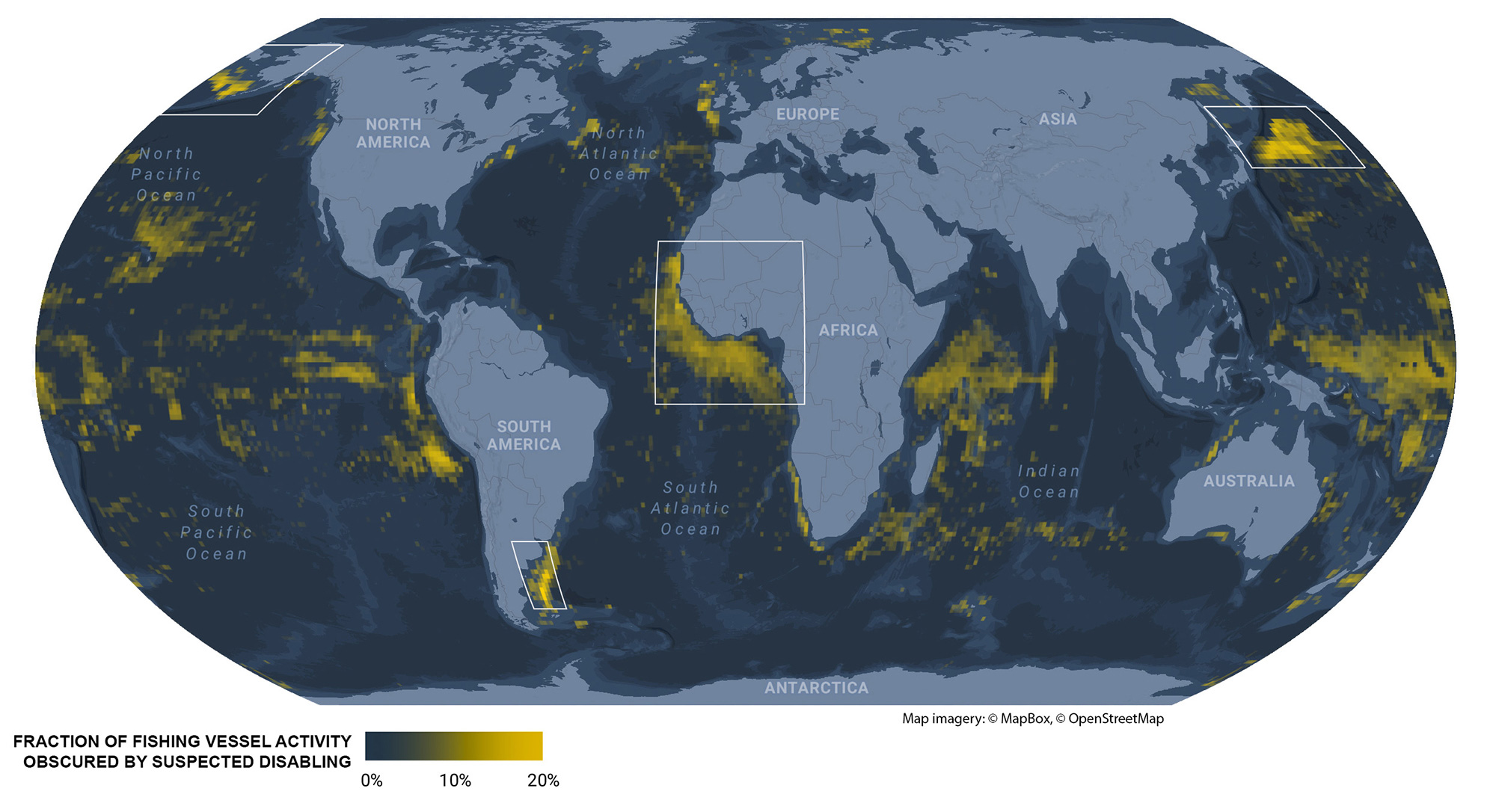

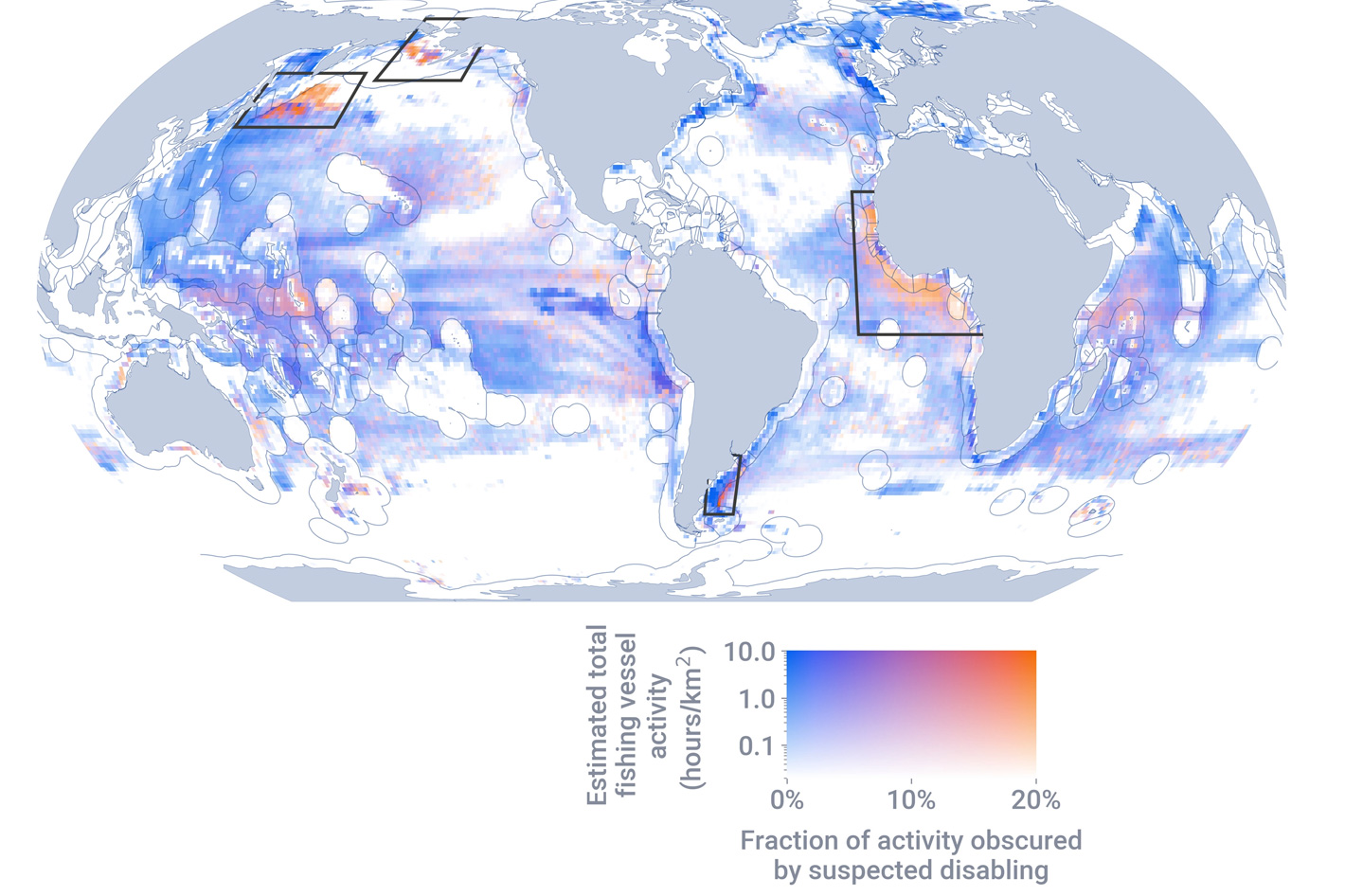

In the study, researchers identified over 55,000 suspected intentional disabling events from 2017 to 2019, obscuring nearly 5 million hours of fishing vessel activity. More than 40 percent of the total hours obscured by suspected AIS disabling occurred across four geographical locations, identified as hotspots, three of which are areas of concern for illegal fishing: the Northwest Pacific and areas adjacent to the exclusive economic zones (EEZs) of Argentina and West African nations. These areas contain rich fishing grounds with limited management oversight.

The study indicates that disabling events were concentrated in waters adjacent to EEZ boundaries, suggesting that vessels may be disabling AIS before entering unauthorized locations to fish illegally. “In many cases, vessels ‘go dark,’ disabling their AIS, as they approach the edge of an EEZ where they are not authorized to fish,” Welch said. “For example, you might see a Korean-flagged vessel heading toward Argentina, and then it goes dark in international waters just outside of Argentina’s EEZ.”

Notably, disabling was particularly common within and adjacent to EEZs with overlapping claims, such as the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) that are disputed by the U.K. and Argentina. The political conflicts in these regions may create blind spots for enforcement.

Disabling events were also common in areas with high transshipment activity, where ships transfer their catch to refrigerated cargo vessels. According to the study, “transshipment can be an efficient way to get catch back to shore and resume fishing quickly, but it can also be used to obscure illegal fishing activity, effectively “laundering” illicit catch through the cargo vessel. In addition, it can foster conditions that allow forced labor to occur on fishing boats, which rarely make their way back to ports.”

Disabling AIS to escape pirates

Disabling AIS to escape pirates

The study also found evidence that some disabling is done for less nefarious reasons by vessels engaged in legal activities. In some cases AIS disabling may be done to hide the locations of good fishing grounds from competitors. The fourth disabling hotspot was caused by U.S. trawlers disabling in U.S. waters off the coast of Alaska—one of the most intensely managed fishing grounds in the world.

The research reveals that vessels flagged to four key nations made up 82% of time lost to suspected disabling events in waters more than 50 nautical miles from shore. Spain had the highest fraction of vessel activity obscured by disabling events (up to 14%), followed by the United States (up to 8%), Chinese Taipei (up to 6%), and China (up to 5%). The researchers do point out, though, that “AIS usage is biased toward vessels flagged to upper- and middle-income countries, thus, these results, in part, reflect who uses AIS (higher AIS usage leads to high opportunity to disable AIS).”

Another reason for disabling a vessel’s AIS is to protect the ship and crew from piracy. Using a database of past incidences, it is evident that vessels switch off AIS in historically dangerous waters to prevent others’ abilities to track and intercept them. The approach demonstrated in this study could be used to support surveillance and enforcement efforts.

“This new dataset is an untapped resource that provides a real opportunity to detect previously unobserved behaviors and illegal fishing activities,” Welch said. “Authorities could use this information to decide where to send surveillance drones or patrol vessels, and it could also be used to focus port inspections on vessels that have disabled AIS adjacent to EEZ boundaries or in transshipment hotspots.”

“This new dataset is an untapped resource that provides a real opportunity to detect previously unobserved behaviors and illegal fishing activities,” Welch said. “Authorities could use this information to decide where to send surveillance drones or patrol vessels, and it could also be used to focus port inspections on vessels that have disabled AIS adjacent to EEZ boundaries or in transshipment hotspots.”