Climate change has made Indigenous whalers or fishers ask, more frequently, “is today a safe day to take my boat out?” The project ‘Backyard Buoys’ aims to provide threaten coastal communities with the data to make the right decision.

Indigenous coastal communities have relied on the ocean for millennia and still do to this day. Climate change, however, is making the ocean unpredictable, and poses a new and urgent challenge.

Rising temperatures and sea levels threaten coastal communities. When fishers or whalers ask that question about safety, they simply do not have the wave data necessary to complement their Indigenous knowledge and make an informed decision. The Backyard Buoys project aims to give them the right answer.

Backyard Buoys empowers Indigenous and other coastal communities in the Pacific Northwest, Alaska and the Pacific Islands to collect, steward and use wave data captured by strategically placed buoys to complement their existing knowledge. This facilitates their blue economy with safer and more efficient fishing, cultural practices, and local entrepreneurs. Wave data are needed to improve safety and to help better understand environmental changes and alert residents to potential breach events. Hundreds of lives, millions of dollars of revenue, and cultural resilience is at stake in each community.

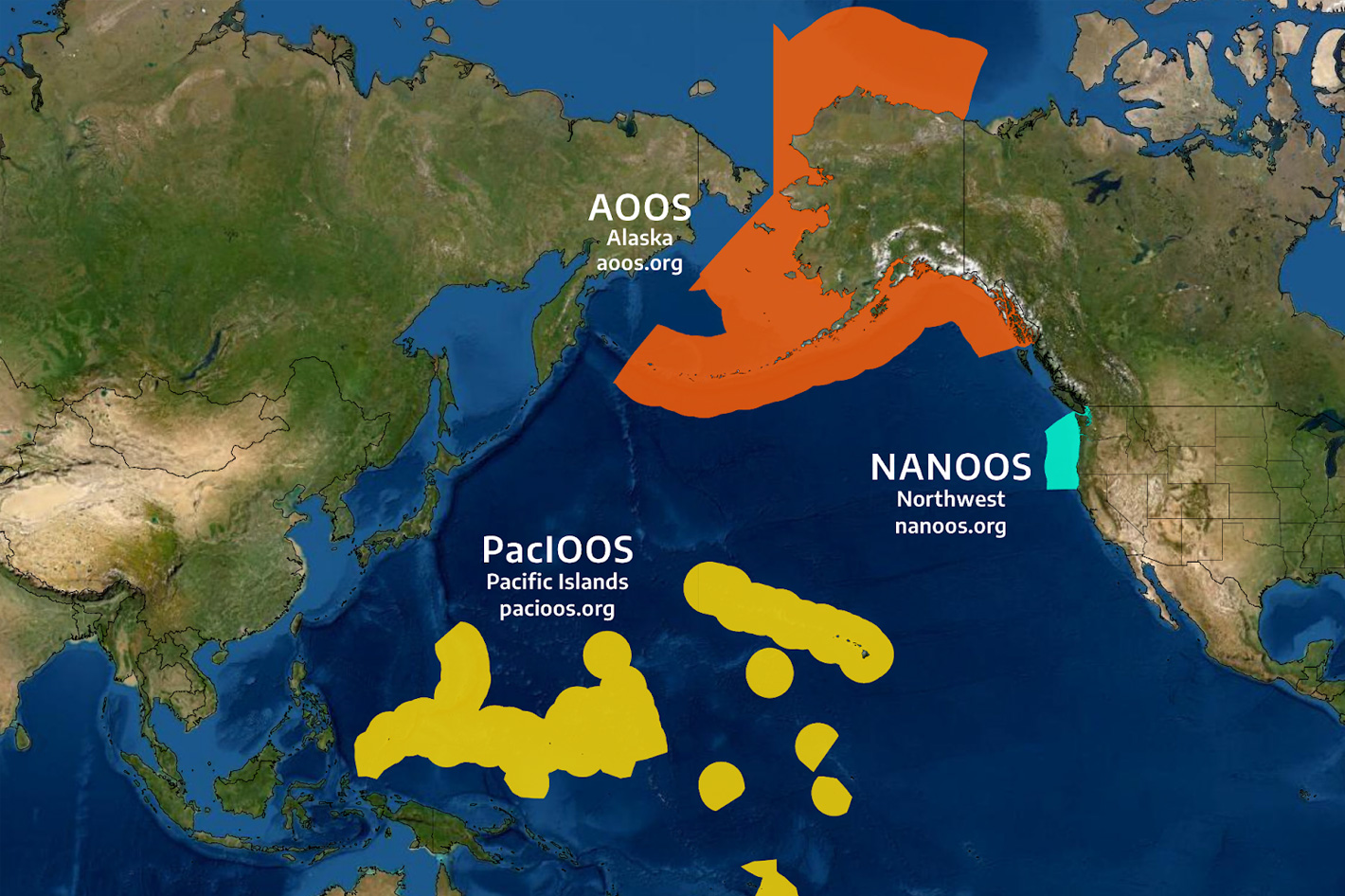

Thanks to a $4.98 million cooperative agreement to three regional associations of the NOAA-led U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing System, the Backyard Buoys’ project has become a reality. As part of this community-led ocean observing project funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Convergence Accelerator program, three regional associations (AOOS (Alaska Ocean Observation System), PacIOOS in Hawai’i and the U.S. Pacific Islands and NANOOS in the Pacific Northwest U.S.), a technology partner (Sofar Ocean), and Indigenous partners from the Pacific Islands, Pacific Northwest, and the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC) entered a partnership to launch Backyard Buoys.

Spotter a basketball-sized buoy

Spotter a basketball-sized buoy

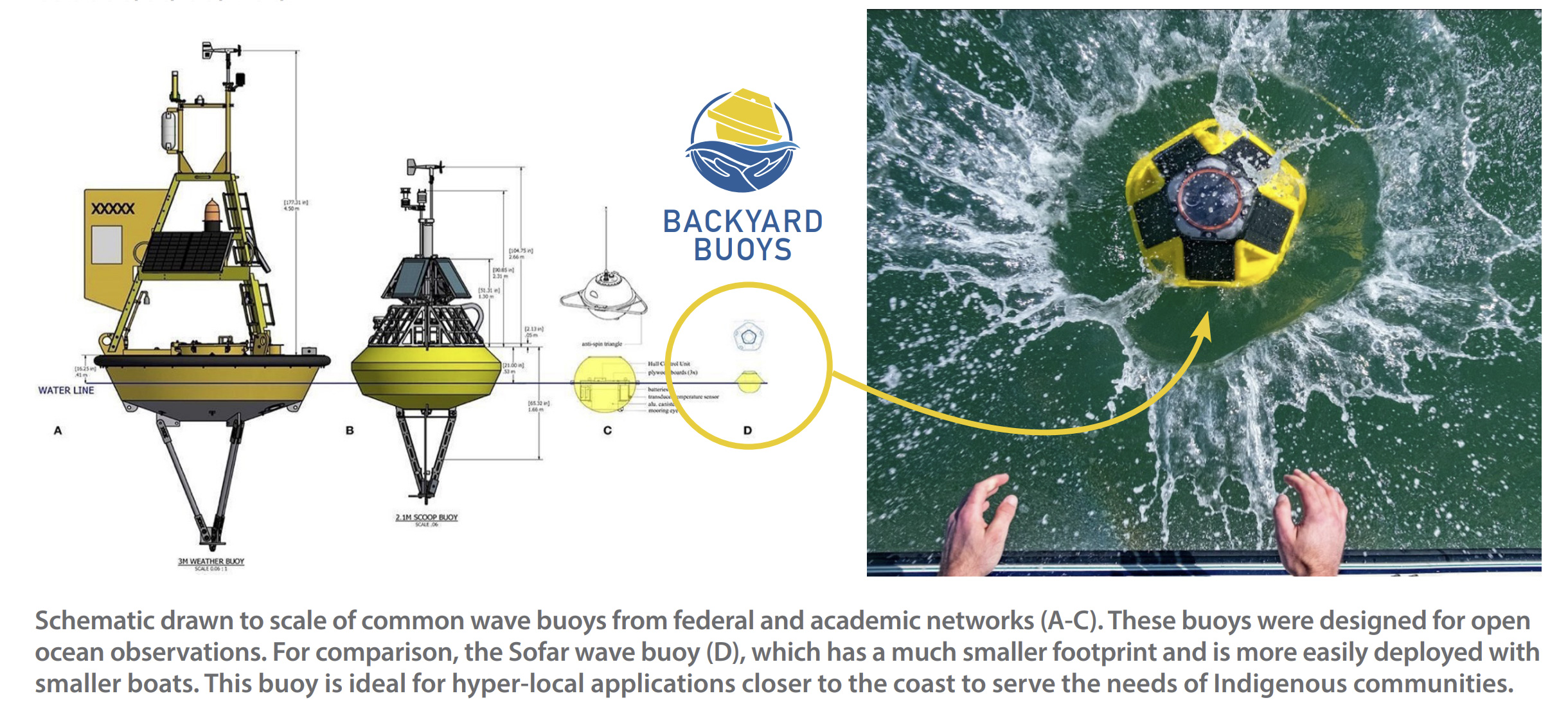

The project relies on Spotter, which is an affordable metocean buoy that collects and transmits wave, wind, sea surface temperature, and barometric pressure data in real-time, developed by Sofar. Easy-to-use, built to last, the Spotter buoy has the size of a basketball, is solar-powered, and is simple to deploy and designed for harsh ocean conditions.

Engineered by ocean scientists, Spotter produces precise, peer-reviewed data that is trusted by the global research community. 24/7 satellite connectivity provides seamless access to ocean data, which is stored in the cloud and delivered via the Spotter dashboard and API. Cellular connectivity enables over-the-air firmware updates.

The accessibility of Sofar’s Spotters is a critical component of the Backyard Buoys project. Most wave buoys are too expensive to buy and maintain, and can only be operated by large national programs with support from specialists. Spotters are low-cost, user-friendly, and human-scale — they can easily be carried by one person — and put wave data in the hands of communities to enhance safety, improve livelihoods, and help inform climate resilience decisions.

Spotter is continuously evolving and, in July 2022, Sofar released the third generation of the platform. This release unveiled a wave of exciting improvements — collectively known as “Spotter 3” — that include a 10x increase in onboard computing power and 40 percent less energy consumption. More robust and reliable, Spotter 3 has a new USB-C interface that simplifies the data transfer and power supply process.

Project has national and global scalability

This can help coastal communities like the one from the village of Taholah, which is a part of the Quinault Indian Nation in Washington, where residents suffer increasingly frequent flooding due to breaches of a protective sea wall during storm events. “Wave data for our region would not only enhance the ability of fishers to decide if conditions are within their boats’ safety parameters but also help the Quileute tribal community to better understand conditions that affect coastal erosion processes,” said Jennifer Hagen, marine biologist and marine policy advisor for the Quileute Tribe.

“This project has the ability to bridge local Indigenous knowledge with scientific data collection, making the information needed for ocean safety decisions more accessible to our local community,” said Fuiava Bert Fuiava, a Samoan vllage chief.

According to Lesley Hopson, executive director of the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, “What appealed to us about the project at the AEWC is that it has a collaborative approach, and it is community-led and community-driven. Our whaling communities are located along the arctic coast of Alaska and rely on the resources from the sea to feed our communities. The sea can be very unforgiving and dangerous, and it changes all the time. This technology will allow us to improve safety for our hunters and better understand environmental changes.”

Although the initial focus of the project is on Indigenous communities in remote areas, whose lives, livelihoods, and cultures depend on sustainable use of ocean resources, those behind it believe that “the project has national and global scalability because it is piloted in three very different regions with diverse environmental conditions and varied ocean uses, providing an opportunity for comprehensive field testing of efforts that can be applied to other locations.”

In the future the project will give communities access to information and insights to empower their own blue economy goals, while creating a system for stewarding these valuable data and observation resources through local ownership.