With the first offshore wind lease sales impending off California, the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and commercial fishermen still have a chasm to gap before the new and old industries can reasonably co-exist, panelists said at the Pacific Marine Expo in Seattle Friday.

BOEM’s early years of reviewing and permitting the first U.S. federal waters wind projects off southern New England failed to anticipate and head off conflicts with the region’s 400-year-old fishing industry, said Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association.

While the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project is moving ahead, BOEM and the developers are still contending with a lawsuit brought by Northeast fishermen with the assistance of the Texas Public Policy Foundation.

A separate lawsuit against the Vineyard project is being pursued by the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a coalition of fishing groups and communities that originally organized out of East Coast ports, questioning the concept of turbines arrayed in one-mile grids on the shallow outer continental shelf.

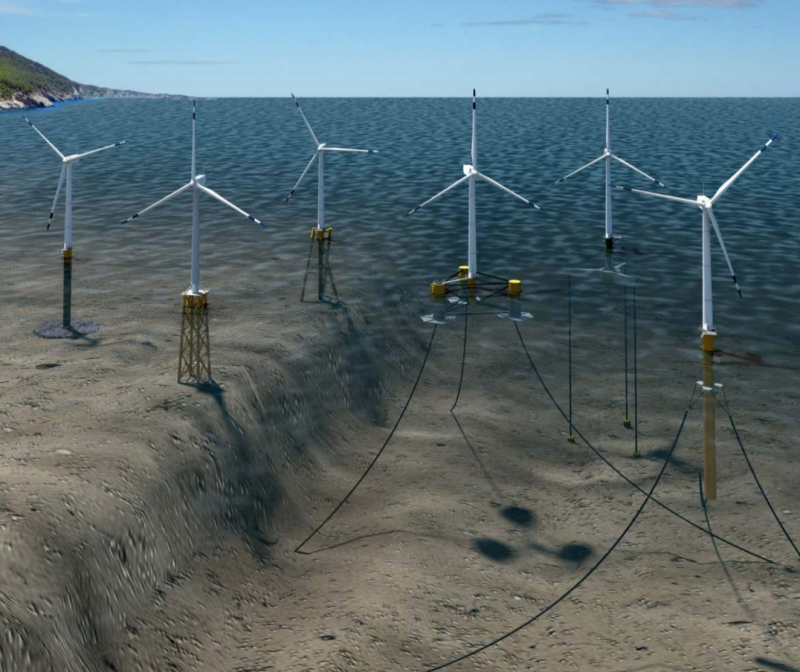

Deeper waters off the West Coast would require the construction of floating arrays – basically turbines on pontoons. The concept would create a seascape different from projects underway in the Atlantic, said Mike Conroy, RODA’s West Coast coordinator.

With shallow-water, monopile foundation turbine towers rising from the shelf, “you might be able to fish around them, in theory,” said Conroy. Floating turbines would have more infrastructure underwater, and off the bottom, including anchor lines and interconnection power cables. Those make it unlikely that anything but fishing on the surface will be possible, he said.

If West Coast wind development makes too much ocean inaccessible to fishing it will have major effects on rural coastal towns where few other full-time jobs are available, said Lori Steele, executive director of the West Coast Seafood Processors Association.

Suggestions for mitigating negative effects on fishing from East Coast wind power have yet to come close to any kind of consensus, and Steele said it’s far too early to talk mitigation on the West Coast. Oregon fishing advocates are just now trying to push BOEM into moving proposed wind energy areas farther offshore and out of potential conflict areas, she said.

In the Gulf of Mexico, the Southern Shrimpers Alliance had some success working with BOEM to remove some highly used fishing areas from wind energy areas planned off Galveston, Texas, and Lake Charles, La.

BOEM officials say they are taking lessons learned from the Gulf of Mexico planning process, and applying them to a new round of wind energy areas under consideration off Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina.

Could that be a sign that BOEM’s relationship with the fishing industry is evolving?

Conroy said he will believe it when he sees results. Offshore energy planners should be coming to fishermen at the very start of the process, he says, to ask where projects can go without creating conflicts.