The Biden administration’s proposal to protect 770,000 square miles with a new mid-Pacific marine sanctuary took center stage Tuesday during a Congressional oversight committee – with commercial fishing advocates arguing the process of setting aside ocean waters can short-circuit requirements for public input in fisheries policymaking.

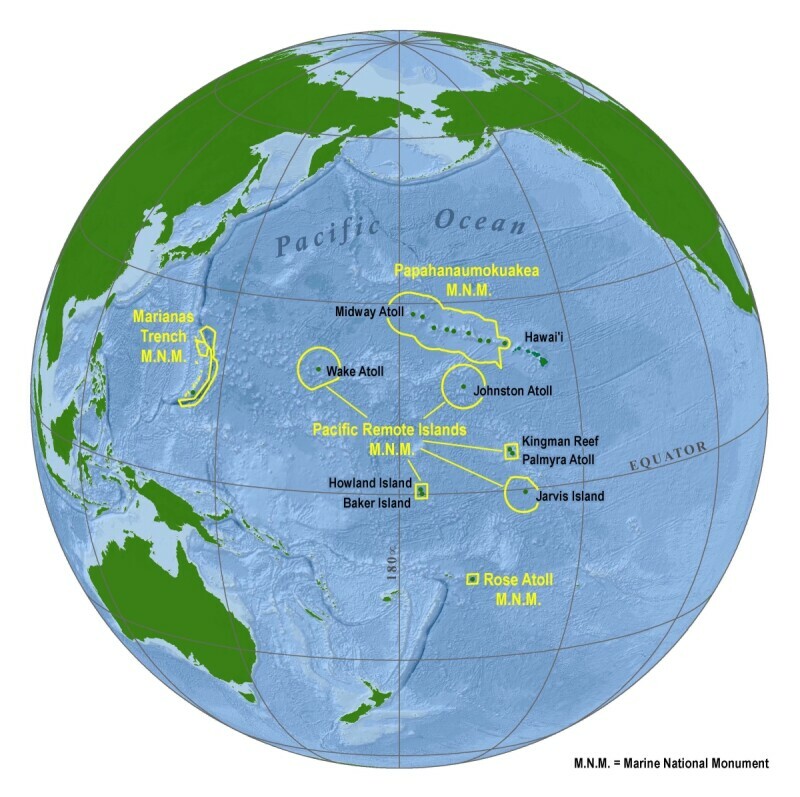

The House of Representatives Natural Resources Committee oversight hearing was billed as “Examining Barriers to Access in Federal Waters: A Closer Look at the Marine Sanctuary and Monument System.” It focused on the plan to expand waters around the existing Remote Island National Monument into a wider sanctuary, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration conducting a scoping process that included a workshop in American Samoa last week.

The prospect of potential future limits on fishing in the region is alarming, said Rep. Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen, R-American Samoa, delegate to Congress.

In its potential extent the proposal is “about to take all of our EEZ (exclusive economic zone) away from us,” said Aumua Amata. American Samoa depends on the purse seine tuna fleet and the cannery it supplies, she stressed: “We are a one-industry economy.”

Meanwhile China’s maritime ambitions in the region are advancing, and it is aggressively pursuing fishing rights from Pacific island nations, said Aumua Amata.

If the United States is to give up its access to waters around the Remote Islands, the nation “is about to become a passive observer in the world’s largest fishery,” she added.

In March the Biden administration announced it is considering creating the Pacific Remote Islands using the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, part of Biden’s broad policy intent to conserve 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030 – commonly referred to as the “30 by 30” plan.

The full conservation area would represent the largest sanctuary of its kind in the world, and would include the existing Remote Islands Marine National Monument and “currently unprotected submerged lands and waters,” according to the March announcement from the White House.

“Such protections would encompass areas unaddressed by previous administrations so all areas of U.S. jurisdiction around the islands, atolls, and reef of the Pacific Remote Islands will be protected.”

Debate over establishing marine monuments and sanctuaries have pitted advocates for those decisive presidential declarations, and others who insisted the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act – and the eight regional councils established under the law – are well up to the task of conservation.

William Johnson Aila, a Native Hawaiian fisherman from Waianae on Oahu in Hawaii, spoke in favor of the sanctuary and extending protections 200 miles out from remote Howland, Baker and Palmyra islands.

“It is one of the remote areas” of the world’s oceans, and protected status will make the region a valuable source of data for monitoring climate and biodiversity changes with global warming, said Aila.

“Most people can’t access these areas,” and marine life there exists in a much different environment from waters around populated islands, said Aila.

He spoke of the experience of being in those waters and coming face-to-face with a “100-pound fish that swims up to look at you” as if to say “what are you doing in my ocean?” That cultural value is one “that never makes its way into Magnuson” fisheries management, he added.

Fishing advocates contended political pressures to declare more protected areas in the oceans are discounting public participation in decision making from fishermen and other stakeholders.

Off the U.S. East Coast, the New England Fishery Management Council worked for years to develop protection plans for deep-sea corals, that covered five times as much area as the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts National Marine Monument, said Eric Reid, a Rhode Island fishery consultant.

Former president Barack Obama originally established the first East Coast marine monument using the federal Antiquities Act – signed by then-president Theodore Roosevelt in 1906, and used then first to stop the looting of Native American sites in the Southwest and protect lands.

Former president Donald Trump moved in 2020 to reverse the Northeast Canyons monument plan to phase out lobster and crab trap gear, but the Biden administration has reinstated the ban on commercial fishing in an area south of Georges Bank. That took effect Sept. 15. Recreational fishing is still allowed, using hook and line gear like the commercial fishery for tuna and swordfish which is now prohibited, said Reid.

The Antiquities Act was “meant to protect shards of pottery” and still allows a president to issue declarations “with little or no public participation,” said Reid. The Magnuson act requires “a more diverse process” for setting decisions, he added.

U.S. Pacific tuna fishermen see regulatory pressure growing on them, and Chinese vessels ready to work just over the line from future sanctuary boundaries, said Bill Gibbons-Fly, executive director of the American Tunaboat Association.

The Hawaii longline fleet lost some 22 percent of its fishing area years ago with the extension of closures around the northwest Hawaiian islands, and incremental restrictions have continued, said Gibbons-Fly.

“It’s as if a ratchet is being cranked, and it only goes one way,” he said. “The cumulative impact is killing us, it really is.”