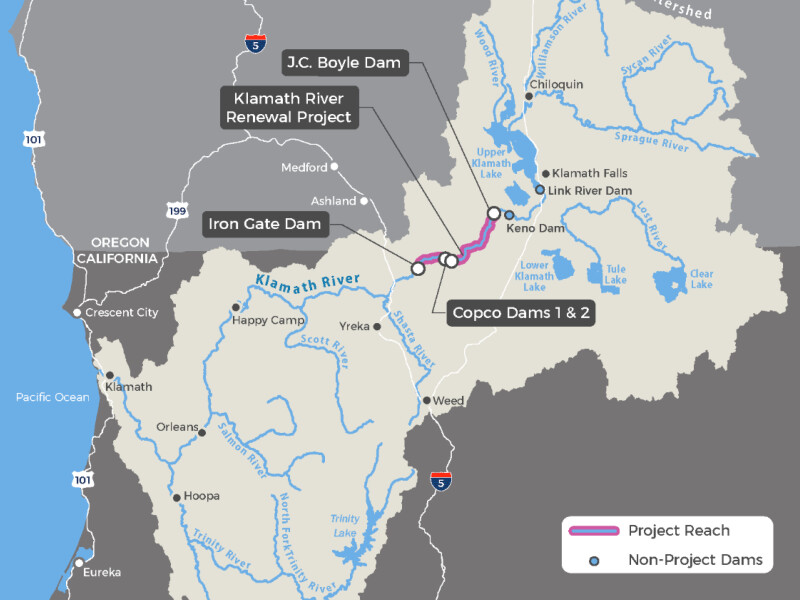

The final hurdle is in sight and expected to be overcome, in the decades-long fight to remove four dams from the Klamath River and hopefully allow restoration of the river’s Chinook salmon population which was once the third-largest in the country, but in recent years has plummeted by as much as ninety-eight percent. The four dams were built between 1903 and 1967 as part of PacifiCorp’s Klamath Hydroelectric Project and are now obsolete. Removing them will provide native migratory fish, like Chinook salmon, access to larger spawning grounds. It will also help restore the natural flow of the river, providing innumerable benefits to the entire ecosystem.

The repercussions that an exhausted river system with a dramatically declining salmon population can deliver are far-reaching and staggering. The slow-moving, warm water gives rise to parasites, like Ceratonova Shasta, which reaches unhealthy levels in this environment and begins to infect and kill the salmon. In addition to parasites, the higher water temperatures are also a deadly threat to the salmon that are necessary for the overall health of the river. After salmon return to the river to spawn and die their bodies provide key nutrients to other organisms in the river. This includes the trees that grow along the riverbanks whose roots help to prevent erosion and to maintain the structural integrity of the riverbank. The Native American Tribes in the Klamath Basin are also heavily dependent on the Chinook salmon, both culturally and for sustenance. Subsistence salmon fishing is a way of life for tribes like the Yurok and the Karuk. Along with the salmon and the river, their way of life is dying.

The way of life of another community is struggling as well. As the Klamath River salmon have suffered from the effects of droughts, irrigation, and dams, so have the commercial salmon troll fishermen of Oregon. Their commercial troll season is regulated based on the lowest stock in the system. This means that if the health of one particular river is in an unacceptable state of decline, in this case, the Klamath, and the Chinook salmon numbers in that river are falling below a sustainable level, actions will be taken when adopting a season structure for the fishermen to safeguard against the impact to that stock going above a certain threshold. That threshold is in place to protect the future of the stock by ensuring that enough salmon return to the river to spawn. (The number of salmon that return to a river each year is known as escapement.)

Officials from the State of Oregon, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, among others, sit down each year to develop a season structure for the commercial fishermen based on a wide range of data and forecasts. They take into account projections of the estimated escapement in each river, the impacts on fish outside of their jurisdiction in places like British Columbia, and the estimated effort that will be made by fishermen, called “boat days.” The Ocean Salmon Management Program, in coordination with ODFW, collects and analyzes information taken by field samplers in Oregon ports including the coded wire tags that were put in some of the salmon as fry. When these salmon are caught and delivered as adults those chips are removed and provide information as to which river system that fish originated from. Scientific models, specific to each river system and based on past studies, are used to determine allowable percentages of fish to be taken.

In recent seasons, the Klamath model has overestimated the effort by the fishermen, causing a loss of fishing days. This will need to be rectified in future seasons but provides insight into just how sensitive these models are to the multitude of factors that are considered in this process and how directly the fishermen are affected. In this year’s open meeting of the Oregon Salmon Commission, no doubt fed up with season cuts on account of the Klamath stock, someone suggested that it might be time to give up on the Klamath fish and take them out of consideration under the assumption that they never actually will bounce back.

At the end of this process, three-season options are presented, and the public is given the opportunity to express opinions about which one seems to be the most desirable before one is adopted by the Pacific Fisheries Management Council. The commercial salmon troll fleet is then given a list of season openers and closures by which they must abide. Just two years ago, the season for the largest zone of the Oregon coast was open for nearly the entirety of what are generally the most profitable months, from June 4th through August 25th, in addition to other periods in the spring and fall. Last year, it was open for four three-day periods in both June and July, and three in August, in addition to openers in the spring and fall. This year, during the prime salmon months, commercial fishermen will be able to troll for salmon for two twelve-day periods in June, two five-day periods and a seven-day period in July, and an eight-day period in August.

These short openers and broken-up seasons are detrimental to an already devastated fishery, as the success of the fleet has been declining in recent years. The seasons in 2016 and 2017 have been declared to be disaster years, disaster requests have been submitted and approved by Oregon for 2018, 19, and 20, and a request is now in for 2021. In the cases of 2016 and 2017, the disaster relief was approved not based on a regional fishery failure, but specifically on the failure of the Klamath fishery. In order for there to be a “fishery failure,” and for a disaster to be subsequently declared, and the fishermen provided with monetary aid, there must be a revenue loss of greater than eighty percent as compared with the average revenue of the most recent five seasons. If this hasn’t occurred, but there has been a revenue loss greater than thirty-five percent, it will be evaluated further. This evaluation must show that “because of a fishery resource disaster, a significant number of those engaged in the commercial fishery have suffered revenue declines that greatly affect or materially damage their businesses,” according to the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. It can also be declared a disaster if there has been a “sudden and precipitous decrease in the harvestable biomass or spawning stock size of a fish stock that causes a significant number of persons to lose access to the fishery for a substantial period of time in a specific area.”

The size of the fleet is indicative of a suffering fishery as well. As recently as 2014 and 2015 more than fifty percent of vessels with permits made commercial salmon landings, and by 2021 that figure had shrunk to less than twenty-five percent of vessels with permits making landings. The last time those numbers were that low was during the season closures of 2008 and 2009 that were caused by extremely low returns in the Sacramento River.

While the season structure has been deemed necessary for the future of the Klamath stock, made clear by the statement from NMFS and PFMC when they released the season structure that, “Due to very limited allowances for Klamath River fall Chinook salmon, significant season cuts are being made in Oregon and California,” it does present problems for the fishermen. The season being open for five days is no guarantee that they will be able to fish all five of those days, if at all. Many of the salmon trollers in Oregon are smaller vessels. The weather may prevent them from leaving port for half or all of an open period. There is no recourse for them if they are unable to fish any of the openers because of the weather. Some of these vessels still have Dungeness crab pots in the water until the beginning of August because they need the second income. They are required to check their crab pots on a regular basis, barring weather. If the only weather window falls on a salmon opener, they are forced to choose between salmon fishing and potentially getting a ticket for not touching their crab pots, or running crab gear and missing out on the salmon revenue. Taking their pots out of the water to be able to make every salmon opener may prove to be fiscally irresponsible if the weather doesn’t cooperate, or the fish are off the bite.

Joe Salvey has been trolling for salmon in Oregon for over forty years. He learned from his father on his dory. He remembers days of catching over a hundred salmon and a trip in 2014 that gave him enough revenue to buy a troller. He has since had to sell that troller and purchase a different boat that can crab as well because there simply wasn’t enough money in salmon. Last year, he bought a gill-netter in Bristol Bay and now spends his summers in Alaska gill-netting sockeye salmon. It was a move that he had to make as he watched his revenue from salmon decline dramatically. He recognized that it was more fiscally responsible to troll in the spring, dock the troller and head north for the summer, and come back for Albacore season before starting gear work in the fall and heading out for another Dungeness crab season come December. He still considers selling it all and buying a larger troller and more permits so he can troll the entire coast for the spring and summer, but he knows that that’s a gamble and that the salmon fishery that he grew up on is no longer a sustainable source of income.

While the removal of the four Klamath dams is by no means a guarantee that the numerous problems Oregon commercial salmon fishermen are currently facing will disappear, it is being lauded as a win for the salmon, the native tribes, and the fishermen, and the entire ecosystem of the river. It will still be an uphill battle for them all. Provided the final approval to remove the dams comes through as expected, it will be the largest dam removal in U.S. history, and, provided everything goes according to the plan, the removal wouldn’t be completed until well into 2024. The Link River Dam will remain upstream to provide control of lake levels and water for irrigation. This could contribute to warm water issues in the future, especially if the drought persists in the region. The large number of juvenile fish that were killed last year as a result of poor river conditions will cause low returns in future years. The lifecycle of the salmon will continue to play out, and the effects of river conditions at this very moment will be seen for years to come. The river, and the salmon, will not simply bounce back, but the restoration of natural flow to the river can optimistically lead to better river conditions for the salmon, the benefits of which the entire ecosystem, and all those that depend on it for their way of life, can one day reap.