North Atlantic right whales, one of the most endangered species in the world, are spending more time in southern New England waters where immense offshore wind energy installations are to be built.

A new analysis, published in the July 29 edition of the journal Endangered Species Research, shows how measures to protect the whale population – estimated at only around 366 animals – will be crucial if the Biden administration’s drive to develop offshore wind is to succeed.

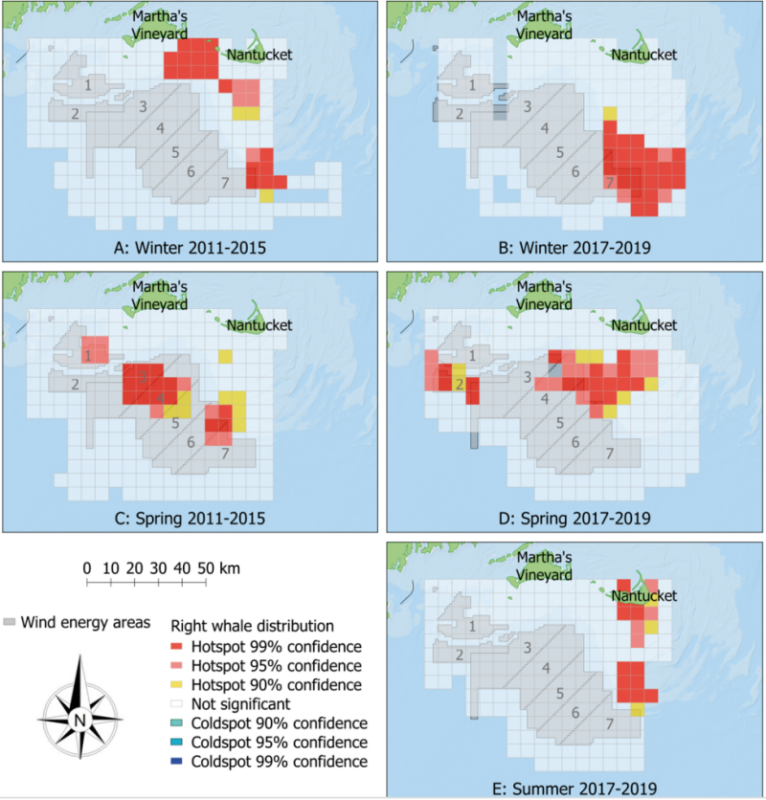

“We found that right whale use of the region increased during the last decade, and since 2017 whales have been sighted there nearly every month, with large aggregations occurring during the winter and spring,” said Tim Cole, lead of the whale aerial survey team at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study, in a summary of the findings issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Marine mammal researchers at the New England Aquarium and colleagues at NEFSC and the Center for Coastal Studies examined aerial survey data collected between 2011–2015 and 2017–2019 to quantify right whale distribution, residency, demographics, and movements in the region.

The New England Aquarium used systematic aerial surveys, and NEFSC and the Center for Coastal Studies directed surveys conducted in areas where right whales were present, to document aggregations of right whales. Aerial photographs of individual right whales to help estimate the whales’ abundance and residency times, and the photos identify individual whales by distinctive patches of raised tissue on their head, lips, and chin, and by scars on their body.

Photographs were matched to catalogued individuals in the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium Sighting Database. A total of 327 unique right whales were photographed in the area by the teams over the study period.

The study used the photographic data in a mark-recapture model to estimate the right whales’ abundance in the area. It showed that between December and May, almost a quarter of the right whale population may be present in the region.

The study also found that the residence time for individuals in the area during the winter and spring has increased three-fold to an average of 13 days over the last decade. Up to 23 percent of the right whale population was estimated to be using the wind areas, off Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Rhode Island from December to May.

That included 30 percent of the population’s females – critical to its survival.

Some female right whales migrate south to calving grounds and give birth off Georgia and Florida.

Right whales exhibit partial migration, a term used to describe a species in which a proportion of a population stays resident in a habitat and another proportion migrates to another habitat, according to Ester Quintana, a scientist who currently works at Simmons University in Boston, Mass., and is lead author of the paper.

"In the case of right whales, all demographic groups have the potential to migrate to the wintering grounds off the southeastern U.S.A., but the migration appears to be condition dependent and varies across demographic groups and years," said Quintana.

"Females may overwinter in the feeding areas in the north and skip the breeding grounds in the south in the years immediately preceding and following calving to increase their energy stores for future reproduction," she said. "On the other hand, juveniles and adult males may travel

to the southern wintering grounds following years of higher prey availability in a northern fall feeding ground."

Their movements up and down the East Coast expose the whales to danger from ship strikes, a leading cause of death and injury along with fishing gear entanglement.

NMFS and lobster fishermen are already working under federal court orders to reduce whale encounters, and environmental groups insist most be done in other maritime sectors.

NMFS regularly issues advisories for mariners to reduce large ship speeds to 10 knots when whales are sighted during aerial surveys. The latest advisory came out Monday for an area southeast of Nantucket – on one of the tracks into New York Harbor that shipping takes into the port’s traffic lanes.

But studies by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the environmental group Oceana found that Automatic Identification System data shows shipping routinely violates those speed limits.

The 10-knot rule is on the minds of wind developers, naval architects and shipbuilders who are figuring out what the workboat fleet should look like for a U.S. wind industry. The new study outlines an array of other dangers for whales.

“The regular presence of right whales in southern New England deserves more attention,” the authors wrote. ”The effects of offshore wind development on right whales are unknown, but this enormous development could have a local impact on right whales at a critical time when they are becoming more reliant on the region.”

The changing behavior of right whales shows offshore energy planning cannot rely on historic migratory patterns, the authors wrote.

"The apparent increased use of this habitat could be related to an increased field effort in recent years, which resulted in a higher number of identifications, and/or to dramatic climate-driven ecosystem changes that have occurred in the past decade," according to Quintana. "Migratory species such as right whales are particularly affected by climate change because they rely on highly productive seasonal habitats."

“Monitoring and mitigation plans should include protocols for the likely presence of right whales throughout the year. Their increasing summer and fall presence deserves special attention since this will overlap with the current schedule for pile driving for turbine foundations in the next few years, the phase of construction considered to have the greatest acoustic impact, which could potentially affect right whale behavior,” according to the paper. “Management and mitigation procedures should be adapted and reevaluated continually in relation to right whales' use of the area."

Wind developers’ mitigation plans will be critical to whale protection. Vineyard Wind has already agreed to “enhanced mitigation procedures to detect and protect right whales from early winter to mid-May, to avoid pile driving from January to April, and to maintain a comprehensive monitoring effort during the other months of the year that construction might take place,” the paper notes.

Those procedures include using real-time acoustic monitoring, keeping certified observers stationed on a vessel at pile-driving sites, and vessel surveys during daylight hours in a 10-kilometer (6-mile) radius around the construction site.

“Studies designed to examine the consequences of acoustic exposure to construction noise are urgently needed,” the researchers wrote. “The area of the potential effect of acoustic exposure can extend far beyond the immediate vicinity of the proposed development and cause behavioral disturbances in animals in a large area. Work is also needed to determine if wind farms alter the habitat’s physical and oceanographic characteristics.

“This may have cascading impacts on the food chain in the region, which could potentially displace right whales to other areas. Estimating the potential impacts of offshore wind farms on right whales or their cause-and-effect relationships will be challenging at a time in which whale numbers and distributions are changing, but this is necessary to inform appropriate strategies for future wind energy development.”

“Implementing mitigation measures by all companies holding leases will be crucial, and should be adapted and reevaluated continually in relation to the whales’ use of the area,” said Cole. “Given the large-scale shifts that the species is experiencing, a variety of studies will be needed to understand potential changes in right whale distribution patterns and to inform appropriate strategies for future wind energy development.”

Funding for the study was provided by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center. NMFS funded publication of the study.