It’s always sad when a boat sinks. We vest our boats with personality, in return for which they serve us loyally, if not munificently. And when a boat goes to the bottom, we realize how vulnerable it always was.

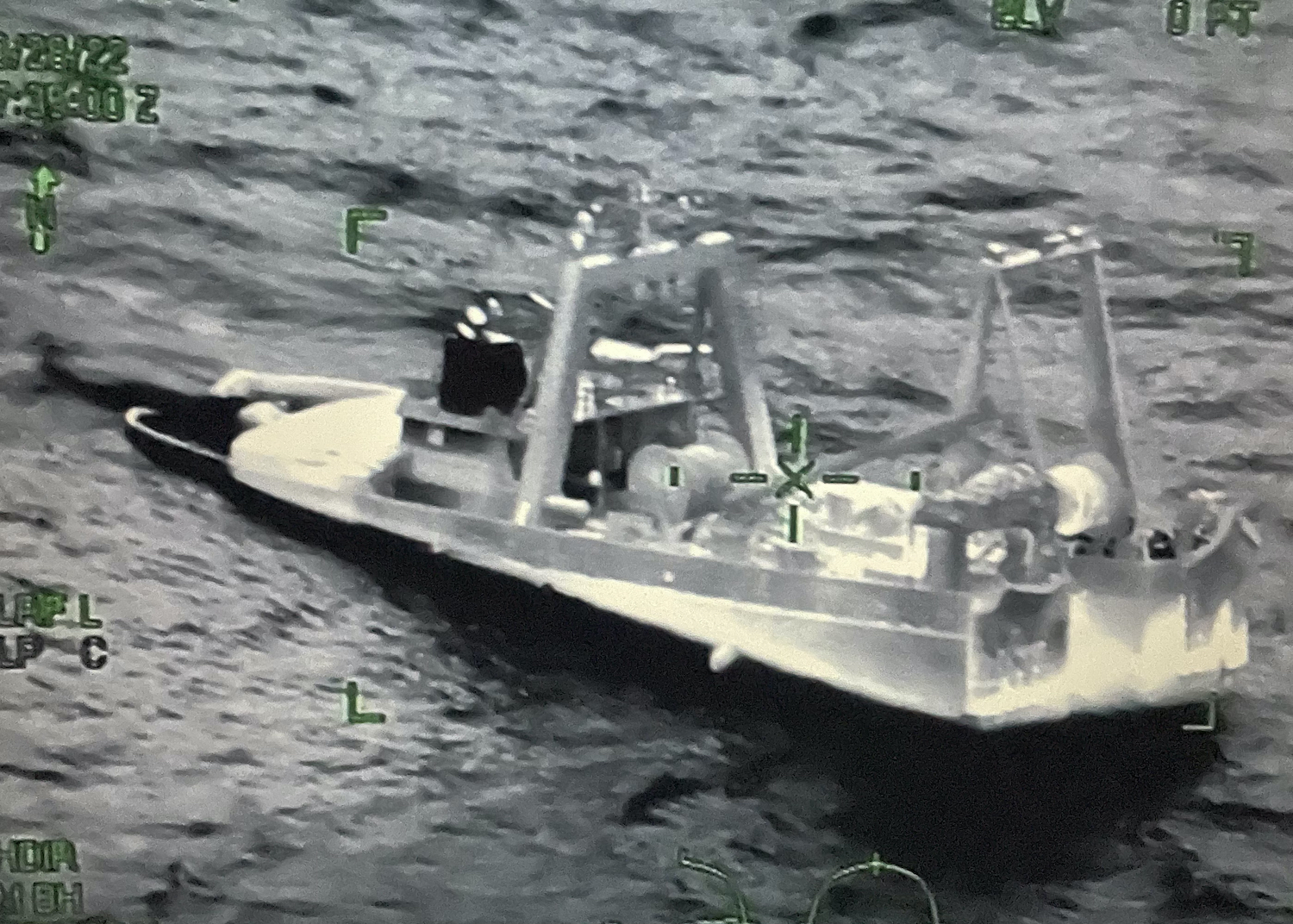

Yet I was especially saddened to learn that the Tremont had gone down after a collision with 1,000-foot containership off Virginia. Fortunately, the captain and crew — 13 fishermen — were rescued.

My guess is that many New England trawlermen, especially those who have been around long enough to call it a day, share my pensive sadness.

Once upon a time, the Tremont and her two-years-older sister, the Old Colony, were at the vanguard of the New England fleet. Which is only saying so much. In 1968, when the Old Colony was launched, the groundfish fleet was overwhelmingly populated by wooden side trawlers, most of them under 100 feet long, primitively appointed, and long in the tooth.

Side rigs were low slung and designed to ride out winter storms on Georges Bank. Deckhands, sometimes a half dozen or more, slept “down forward” in a cramped fo’c’sle from which they came and went by ladder. Food was kept on fish-hold ice and cooked on an oil stove, which also supplied heat, and eaten at a narrow table between two converging rows of bunks. There was no head and no running water, but crewmen lived here for up to 10 days at a time and were glad to be warm and dry.

The Tremont and the Old Colony were 130-footers built of steel. They were new and well found, with galleys where crewmen could gather and drink coffee and shoot the breeze. They were built to fish any weather and had a higher profile than the side trawlers.

Yet as I have tried to explain, being at the vanguard of the New England fleet was not the maritime equivalent of putting a man on the moon. If the Old Colony and the Tremont had a certain primacy on the Boston Fish Pier, on Georges they trawled in the shadows of vessels more than twice their length from Europe and the Soviet bloc.

Moreover, the Europeans, particularly the Germans, had a greater appreciation for the role of technology in finding and catching fish than did the investors in our groundfish fleet.

Indeed, the Tremont and Old Colony were stern trawlers at a time when many New England fishermen doubted the wisdom of handling the net over the stern.

For one thing, this meant hauling back with the vessel going ahead. In the event of a hang-up, the conventional wisdom held that stern rigs were more likely to rimrack the net by dragging it over whatever had snagged it. Side trawlers hauled back “in neutral” and tended to lift the gear straight up from the bottom. And drying the net over the side of an eastern rig afforded the crew a much better view of the twine than they were likely to get hauling it up a narrow stern ramp.

Ultimately it was an academic issue. The invention of the net reel spelled the end for side trawling.

Whatever their technological shortcomings, the Old Colony and the Tremont spoke to growing American awareness of the value of the New England’s fish, which until then had been most appreciated by the distant-water fleets of foreign nations.

(For an insightful look at this era, there is no finer source than “Distant Water” by William Warner. It is out of print, but you may be able to find it on Amazon, as I was compelled to do after loaning out my copy, or at the public library. Warner, a gifted writer, won a Pulitzer Prize for “Beautiful Swimmers,” a book about blue crabs and Chesapeake watermen.)

In 1976, Congress enacted the 200-mile limit, which spelled the end of what Warner had described as “the great floating cities” from across the ocean that had populated Georges.

The United States responded by offering incentives for investment in fishing vessels, primarily the tax haven capital construction fund. Technology followed the money. Loran C, which facilitated navigation to within 50 feet, and sonar became common in the wheelhouse of the humblest trawlers. Not long after, the old black-and-white fishfinders that gobbled rolls of expensive paper gave way to so-called color machines that presented fish and the bottom vibrantly on a screen. Steel boats built in yards from Maine to Alabama became the new floating cities on Georges.

The Tremont, with six years on Georges under its belt when the 200-mile-limit came in, beat even the early adopters to the punch. Five months after the boundary went into effect, Warner wrote in the epilogue to “Distant Water,” the Tremont was catching fish at such a pace that after supper skipper Carl Spinney would leave him to stand watch while he helped his backed-up crew tend to the catch.

Nothing lasts forever. The Tremont made its way to Alaska, where in 2009 and going on 50, it was the oldest vessel in the Amendment 80 groundfish fleet. Eventually, it made its way back to New Bedford. And then, to a place 63 miles off Chincoteague, Va.

But once it had been our future.