The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is working with coastal states to come up with plans for potentially compensating fishermen for lost fishing grounds and other negative effects of developing offshore wind turbine arrays.

Fishing industry advocates are pushing anew to get fishermen deeply involved now to minimize impacts from sweeping plans to rapidly develop a U.S. offshore wind industry — and hoping to limit damage to the U.S. food supply.

The government’s drive toward creating more offshore wind energy areas in the New York Bight is looking like a repeat of its mistakes in planning southern New England projects and needs to be braked, fishermen said at an Aug. 6 meeting in New Bedford, Mass.

“It’s going to be responsible for the destruction of a centuries-old industry that’s only been feeding people,” Bonnie Brady, executive director of the Long Island Commercial Fishing Association, told officials of the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

“If you really want to do that right thing, stop everything” until wind energy areas can be better assessed to accommodate power generation while maintaining fisheries, said Brady.

Speaking with fishermen via a Zoom online link, BOEM Director Amanda Lefton opened the meeting by saying the agency has learned from experience and is working to engage better with the fishing industry and head off conflicts.

“We have to improve our engagement with the fishing industry,” said Lefton. “We are doing our best to make changes.”

Some changes are coming in how BOEM will review plans for the New York Bight — the arm of the Atlantic between Long Island and New Jersey, adjacent to the voracious New York regional energy market and already targeted for major offshore wind projects.

Future new leasing will include requirements for wind developers to report more frequently and be more accountable for how they will deal with issues of environmental impact and effects on fishermen and other maritime users, BOEM officials said.

Fishermen said they are skeptical after seeing past performance by the agency and wind developers.

“When we give feedback… we want to see it taken seriously and put into the project,” said Katie Almeida, senior representative for government relations at The Town Dock, Point Judith, R.I. “We just need to see some of what we’re saying brought forward… and incorporated into wind farm planning.”

“We’ve only been asking for this for six years,” Almeida added. “This can’t be just going forward” with future leases, but should be applied to approved projects like Vineyard Wind and South Fork off southern New England, she said.

Fishing advocates urged BOEM to approach planning on a wide regional basis, saying the experience in southern New England has been project by project.

“It’s a divide-and-conquer approach, and it’s not a reasonable approach for a federal agency,” said Peter Hughes, general manager of Atlantic Capes Fisheries in Cape May, N.J.

BOEM is trying to do better with the New York Bight wind energy areas, including proposed vessel traffic lanes, said Luke Feinberg, a project coordinator with the agency.

The need to think regionally should have been evident from the start, said Brady.

“I was the one who had to tell them there were like six other states (fleets) that fished there” from Virginia to New England, she said. “That’s where these guys live.”

Compensation may take shape

One week earlier, the Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, a coalition of fishing groups and coastal communities, heard about compensation possibilities in an informal conference call with Lefton and her staff, said RODA Executive Director Annie Hawkins.

Lefton mentioned that her agency would be working with state government officials to explore “compensatory mitigation” for fishermen forced out of work by wind farm development, and would begin scheduling meetings for that effort. It also came up during a BOEM presentation to the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council in June, said Hawkins.

But Hawkins says that process is backward in not including fishermen at the onset of discussions. The funding method needs to be publicly discussed, too, she said.

“It’s an impact fee; it’s not mitigation,” said Hawkins. The funding should be calculated early and could be incorporated into wind developers’ power purchase agreements with states, “not doing this at the 11th hour,” she said.

It must be a regional approach, not project by project, and compensation should come after regulators and developers have done everything possible to minimize negative impacts, Hawkins added.

“We want that at the end, after we’ve done everything possible to eliminate the need,” she said.

That must include goals for minimizing disruption to the U.S. food supply, Hawkins and other industry advocates say. They foresee potential losses across fisheries, from high-value products like scallops to routine commodities like surf clams that go into canned chowders.

In online BOEM scoping meetings, longtime clam industry spokesman David Wallace emphasized the fleet is at risk of losing large parts of its traditional grounds.

“If there are no marginal areas to fish, we go out of business,” said Wallace. The government and developers could step in with dedicated funding to compensate for losses, assessed on a per-megawatt basis to pay reimbursement for gear damage and loss of fishing grounds, he said.

Surf clam and scallop fishermen said the deeper ecological and hydrological impacts of building potentially hundreds of turbines need intense study.

“Nothing has been done,” said Guy Simmons, senior vice president for marketing, product development, fisheries science and government at Sea Watch International, a major East Coast surf clam operator, during the Aug. 6 meeting.

Adding those new structures could alter the Mid-Atlantic cold pool, the seasonal stratification in ocean water temperatures that is a key factor in marine species’ life cycles, said Simmons.

“The currents around the turbines are exactly what breaks down the cold pool,” said Simmons, adding “they need to stop everything right now… until the proper environmental considerations” have been studied.

“We are taking a hard look at the hydrodynamic implications,” replied Brian Hooker, a marine biologist with BOEM, who added that scientists at the University of Massachusetts and Rutgers University are likewise investigating how new structures might change ocean conditions.

“We know that when you put a structure in the water, you change currents,” said New Bedford scallop fisherman Eric Hansen. Other effects from building towers and their rock-armored foundations will be increases in blue mussels — competitors to scallops for food in the water column — and scallop predators, including moon snails and sea stars, said Hansen.

Scallop fleet recommends

buffer areas

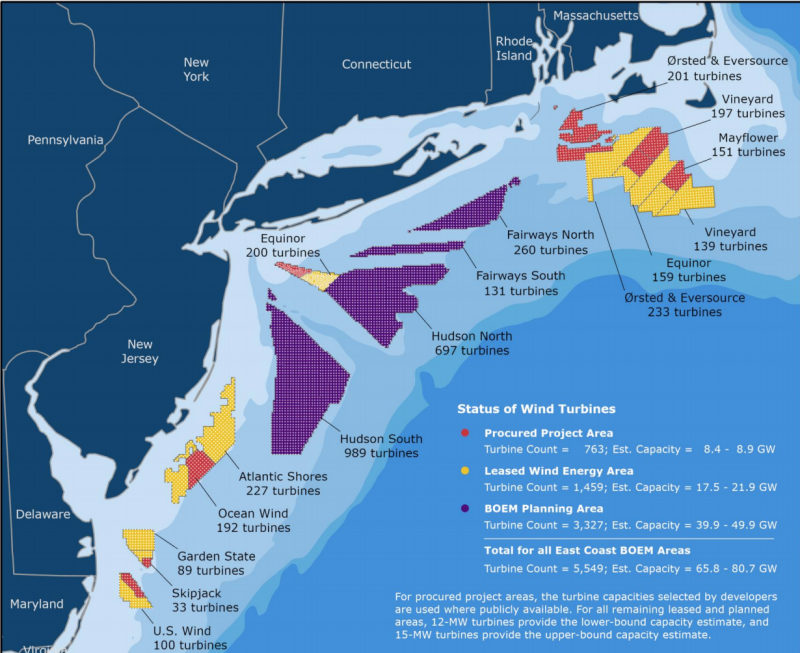

The industry group Fisheries Survival Fund and the Port of New Bedford say the New York Bight plans will threaten the entire East Coast scallop fishing industry that brings in more than $425 million dockside annually and much more to the larger U.S. economy.

They say one immediate step should be creating a 5-nautical-mile buffer zone between the southeastern edge of the Hudson South Lease Area that’s been proposed by BOEM, and the Hudson Canyon Access Area, highly productive scallop grounds that have supported the industry’s immense success over the last 20 years.

In the late 1990s, fishing pressure, declining scallop numbers and fishermen catching smaller scallops brought the fishery to crisis. But fishermen, scientists and regulators regrouped, creating a system of rotational scallop area management that federal scientists say has added more than $1 billion in revenue to coastal communities.

The proposed buffer zone would create a 5-nautical-mile strip inside BOEM’s mapped Hudson South wind energy area, standing off any future turbine construction from the southeastern edge that borders the Hudson Canyon scallop access area, said David Frulla, a lawyer with the Washington, D.C., firm Kelley Drye & Warren, who has represented the fund and other fishing groups.

“The buffer zone’s purpose is to make sure there is not a wind farm hard up against an access area,” said Frulla.

Scallops were worth well over $500 million to coastal economies in 2019 and nearly $750 million “when taking into account their processed value. And this does not include the additional economic value added by the remainder of the supply chain until the product ultimately reaches consumers in markets and restaurants,” according to the Fisheries Survival Fund.

Scallops are a colossal part of New Bedford’s economy, bringing in $265 million in 2019, or 80 percent of the city’s dockside value that year, according to the New England Fishery Management Council.

With their high per-pound values, scallops have an outsized value for ports large and small. Right behind New Bedford in 2019 was Cape May, N.J., with almost $54 million, or 81 percent of its dockside value. Sixty miles north on Long Beach Island, scallops brought in $19.4 million that year, 77 percent of the sales.

While offshore wind development may bring new jobs and economic development to coastal communities, “the benefits should not come at the expense of those who have historically relied on the scallop fishery to provide for their families,” the group says.

Right whales, wrong areas

North Atlantic right whales, one of the most endangered species in the world, are spending more time in southern New England waters where immense offshore wind energy installations are to be built.

An analysis published in the July 29 edition of the journal Endangered Species Research shows how measures to protect the whale population — estimated at only around 366 animals — will be crucial if the Biden administration’s drive to develop offshore wind is to succeed.

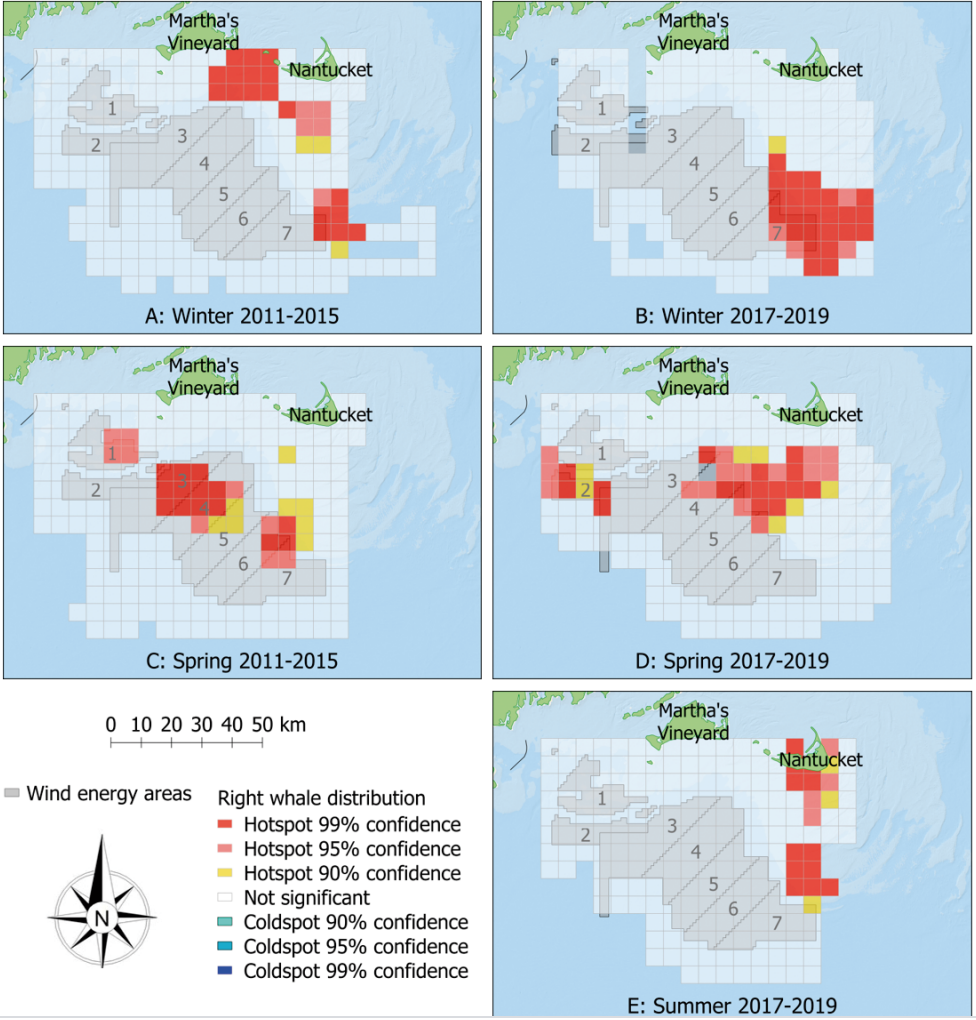

“We found that right whale use of the region increased during the last decade. And since 2017, whales have been sighted there nearly every month, with large aggregations occurring during the winter and spring,” said Tim Cole, lead of the whale aerial survey team at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center and a co-author of the study, in a summary of the findings issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Marine mammal researchers at the New England Aquarium and colleagues at the science center and the Center for Coastal Studies examined aerial survey data collected between 2011-15 and 2017-19 to quantify right whale distribution, residency, demographics and movements in the region.

The New England Aquarium used systematic aerial surveys, and the science center and the Center for Coastal Studies directed surveys conducted in areas where right whales were present, to document aggregations of right whales. Aerial photographs of individual right whales help estimate the whales’ abundance and residency times, and the photos identify individual whales by distinctive patches of raised tissue on their head, lips, and chin, and by scars on their body.

Photographs were matched to catalogued individuals in the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium Sighting Database. A total of 327 unique right whales were photographed in the area over the study period.

The study used the photographic data in a mark-recapture model to estimate the right whales’ abundance in the area. It showed that between December and May, almost a quarter of the right whale population may be present in the region.

The study also found that the residence time for individuals in the area during the winter and spring has increased three-fold to an average of 13 days over the last decade. Up to 23 percent of the right whale population was estimated to be using the wind areas, off Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Rhode Island from December to May.

That included 30 percent of the population’s females — critical to its survival.

Their movements up and down the East Coast expose the whales to danger from ship strikes, a leading cause of death and injury, along with fishing gear entanglement.

NMFS and lobster fishermen are already working under federal court orders to reduce whale encounters, and environmental groups insist more be done in other maritime sectors.

NMFS regularly issues advisories for mariners to reduce large ship speeds to 10 knots when whales are sighted during aerial surveys. But studies by NOAA and the environmental group Oceana found that AIS data shows shipping routinely violates those speed limits.

“The regular presence of right whales in southern New England deserves more attention,” the authors wrote. “The effects of offshore wind development on right whales are unknown, but this enormous development could have a local impact on right whales at a critical time when they are becoming more reliant on the region.”

The changing behavior of right whales shows offshore energy planning cannot rely on historic migratory patterns, the authors wrote.

Wind developers’ mitigation plans will be critical to whale protection. Vineyard Wind has already agreed to “enhanced mitigation procedures to detect and protect right whales from early winter to mid-May, to avoid pile driving from January to April, and to maintain a comprehensive monitoring effort during the other months of the year that construction might take place,” the paper notes.

Amid the offshore wind debate, wind power skeptics saw a shutdown of four turbines at the Block Island Wind Farm — the first U.S. commercial project off Rhode Island — as a warning sign.

But a spokesman for operator Ørsted called the summer outage a break for normal scheduled maintenance. Responding to news media inquiries, the company said that included structural inspection of the turbines, in operation since fall 2016.

“Part of the work being conducted is the repair of stress lines identified by GE in the turbines,” according to an Aug. 11 statement from the company. “We put four turbines on pause as a precautionary measure and carried out a full risk assessment, which showed the turbines are structurally sound. We expect to complete those repairs and all maintenance in the next few weeks as scheduled.”