Officials at NOAA announced on Thursday 2 June 2022 that they expect an average-sized “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico this summer.

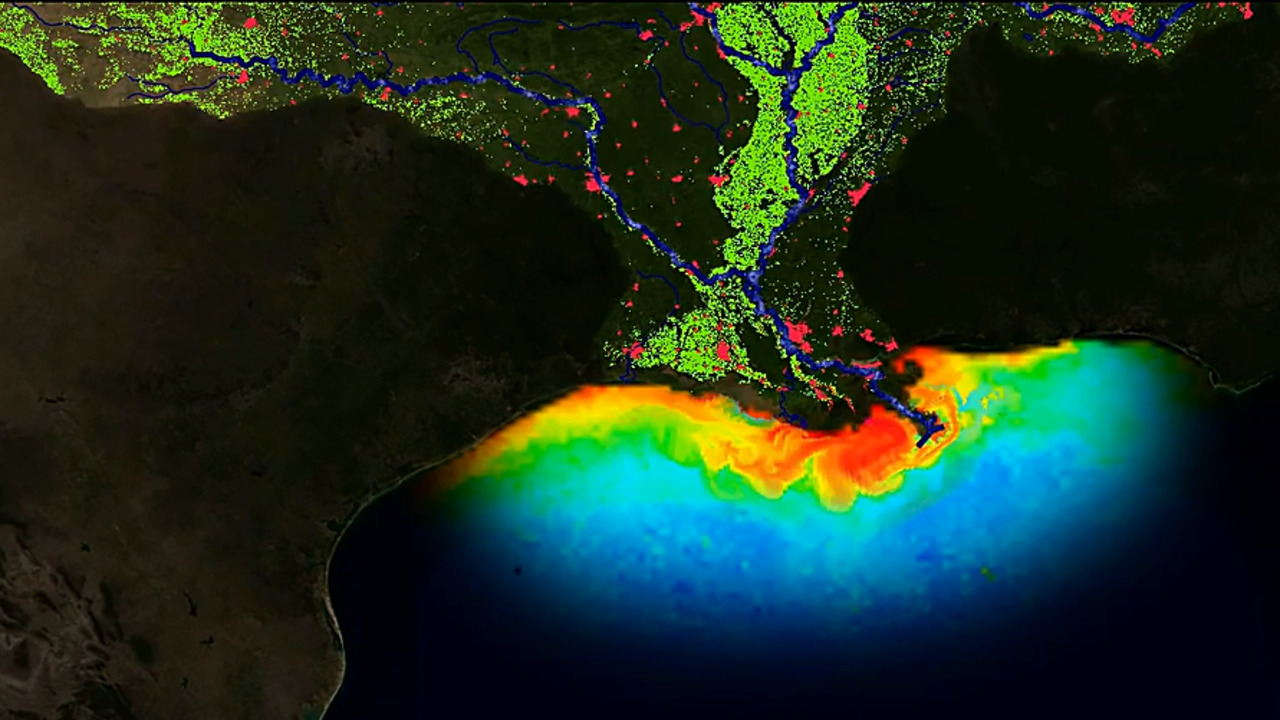

That moniker is given to the area of waters in the Gulf of Mexico that have insufficient oxygen levels to support most marine life. It’s created by runoff of fertilizers and other nutrient-rich pollutants from communities – both rural and urban – that feed into rivers and streams that eventually connect to the Mississippi River, which feeds the Gulf.

The pollutants create an atmosphere that leads to massive algae blooms that deplete oxygen. NOAA officials say that fish, shrimp, and crabs are able to move to safer waters, but marine life that’s unable to move out of the dead zone can die due to the lack of oxygen.

“The Gulf dead zone remains the largest hypoxic zone in United States waters, and we want to gain insights into its causes and impacts,” said Assistant Administrator of NOAA’s National Ocean Service Nicole LeBoeuf in a statement. “The modeling we do here is an important part of NOAA's goal to protect, restore and manage the use of coastal and ocean resources through ecosystem-based management.”

This year’s summertime dead zone is expected to be about 5,364 square miles in size, or about 500 square miles larger than the state of Connecticut. Since NOAA began charting the Gulf dead zone 35 years ago, the average size has been 5,380 square miles.

Last year, officials forecasted a smaller dead zone of 4,880 square miles, but two months later, after experts were able to chart the waters, the actual dead zone was determined to be 6,334 square miles.

The largest dead zone ever measured occurred in 2017 when the year’s hypoxic zone was 8,776 square miles.

Stakeholders in the Interagency Mississippi River and Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force eventually want the dead zone contained to 1,900 square miles annually.

As part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Congress passed last year, the Environmental Protection Agency plans to spend USD 60 million (EUR 56 million) to find ways to reduce the nutrient-rich sediment entering into the Gulf.

“The Hypoxia Task Force has a transformational opportunity to further control nutrient loads in the Mississippi River Basin and reduce the size of the hypoxic zone using Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding,” said John Goodin, director of U.S. EPA Office of Wetlands, Oceans and Watersheds, in a statement. “This annual forecast is a key metric for assessing the progress the Hypoxia Task Force is making.”

This story first appeared on SeafoodSource.com and is republished here with permission.