Discarded fishing gear is a major contributor to ocean pollution. According to Ben Kneppers, who along with David Stover and Kevin Ahearn, co-founded the fishing net recycling company, Bureo, around 600,000 tons of fishing gear ends up in the ocean every year and continues to kill marine life.

“No fisherman wants to contribute to the problem,” says Kneppers. “But they don’t always have alternatives.”

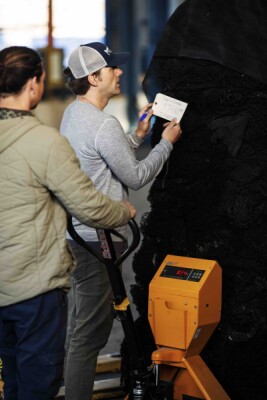

With support from outdoor clothing and equipment maker Patagonia and other companies, Bureo, based in Oxnard, Calif., and Concepción, Chile, started processing high density polyethylene from trawl nets into visors for hats.

“We first got a grant from Chile in 2013, and then Patagonia invested in us in 2014,” says Kneppers. Since then, Bureo has had two more funding rounds, has expanded into nine nations and is processing around 1,600 tons of polyethylene and nylon from trawls and purse seines.

“We’re really focused on the nylon now,” says Kneppers. “It turns over faster in the recycling and is a clean fiber source. Patagonia is using it in swim trunks and in its down sweater, which is one of its signature items.”

While Bureo collects a considerable amount of nylon from the purse seiner fleet in Chile, the company does not take nylon nets from the country’s abundant salmon farms.

“We took a firm stance early on to not get involved with the aquaculture industry,” Kneppers says. The mission, he notes, besides generating viable and valuable products from waste, is to serve the fishing industry. “We go into communities and set up however they want. If they want us to come every month and collect old nets, or set up a dumpster, that’s what we do.”

An important part of recycling is to create savings on an energy level, and Kneppers points out that the carbon footprint of recycling useable fiber from fishing nets is about 20 percent lower than that of creating virgin fiber. “And we’re working to reduce that,” he says. “We’re working on converting our plant in Chile to 100 percent renewable energy.”

With the company processing only a fraction of a fraction of the available fishing net waste stream, Kneppers sees room for growth. “The garment industry needs this,” he says. They can’t get enough of the fiber they need.”