Existing vessel speed limits are inadequate to protect endangered north Atlantic right whales from lethal collisions, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is proposing to expand 10-knot speed limit zones.

NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service on Friday announced the new rule proposal, which would also extend speed restrictions, now on vessels over 65 feet, down to 35 feet. That would make many more fishing and recreational vessels subject to mandatory speed restrictions.

The move on smaller boats comes after a 2021 incident when a young right whale calf died after it was struck by a 54-foot sportfishing yacht inbound to a Florida inlet.

Proposing stricter speed limits comes as NMFS is under pressure to do more for the whales. In January 2021 an analysis by the agency found speed restrictions are often ignored, according to automatic identification system (AIS) ship tracking.

A similar July 2021 study by the environmental group Oceana found most vessel traffic by far has been exceeding speed limits declared by NMFS, by as much as 90 percent in some areas.

The problem was seen to be growing off the Southeast U.S. coast, where container ship traffic transits are increasing to expanding ports like Savannah, Ga., and Charleston, S.C. – along a reach where female right whales migrate toward warm-water calving grounds.

Studies have shown that ship speeds of 10 knots or less can reduce the danger of a ship collision being fatal to whales by 80 percent to 90 percent, according to Oceana.

“The changes would broaden the spatial boundaries and timing of seasonal speed restriction areas along the U.S. East Coast,” according to the announcement by NOAA, which initiated a 60-day public comment period on the proposal until Sept. 30.

“Collisions with vessels continue to impede North Atlantic right whale recovery. This proposed action is necessary to stabilize the ongoing right whale population decline, in combination with other efforts to address right whale (fishing gear) entanglement and vessel strikes in the U.S. and Canada,” said Janet Coit, NOAA’s assistant administrator for fisheries.

The key problems seen by NOAA experts include the need to regulate small vessel speeds and “misalignment between areas and times of high vessel strike risk and current Seasonal Management Areas spatial and temporal bounds."

The northern right whale population is one of the most endangered species in the world, with a total surviving population now estimated at only around 340 animals, including about 100 females that can bear young.

There have been 51 documented right whale serious injuries and deaths in U.S. and Canadian waters since 2017. Climate change and resulting shifts in the whales’ food supply and seasonal movements are stressing the population further.

“However, vessel strikes and entanglements continue to drive the population’s decline and are the primary cause of serious injuries and mortalities. North Atlantic right whales are especially vulnerable to vessel strikes due to their coastal distribution and frequent occurrence at near-surface depths,” according to NMFS. “This is particularly true for females with calves.”

In the last two and a half years NMFS documented four cases of death or serious injury from vessel strikes in U.S. waters.

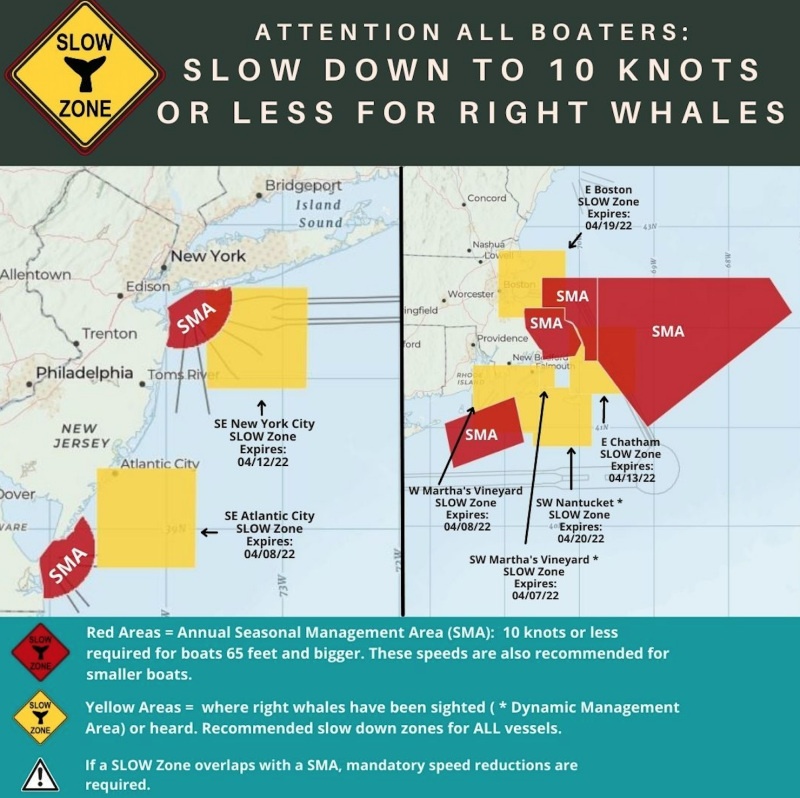

The agency has tried to reduce the danger by creating mandatory seasonal speed zones in areas where right whales are known to congregate at certain times of the year, and shifting “dynamic speed zones” where mariners are asked to keep 10-knots speeds when whales are known to be present.

Proposed changes to the speed limit rule would set up a new mandatory Dynamic Speed Zone program, establishing temporary 10-knot transit zones when right whales are detected outside the designated Seasonal Speed Zones.

The rule’s safety provisions would be updated, allowing vessels to exceed the 10-knot restriction in limited circumstances.

“We have made progress in addressing the threat of vessel strikes, but additional action is warranted to further reduce the risk of lethal strike events to ensure the species can get back on track to recovery,” said Kim Damon-Randall, director of NMFS’ Office of Protected Resources.

NMFS has been focused on reducing entanglement danger from lobster trap gear, and the agency is under unrelenting pressure from environmental groups who say its efforts are not enough. A federal judge in Washington, D.C., recently ruled in favor of those complaints, and wants NMFS to come up with new solutions.

Advocates for the lobster industry welcomed the NMFS move to do more on the danger to whales from ship strikes. Lobster fishermen have worked to reduce hazards from their gear while ship strike losses have continued, the Maine Lobstermen’s Association said Friday.

“Data also show that there has not been a single known right whale entanglement in Maine lobster gear in almost 20 years and Maine lobster gear has never been linked to a right whale death,” according to statement from MLA Executive Director Patrice McCarron. “Since 1997, Maine Lobstermen have taken many actions to protect right whales from entanglement, removing thousands of miles of rope from the water, keeping rope off the surface where a whale might feed, putting weak links in our rope that a whale could break free, and marking out lines so we know if Maine lobster gear is responsible for an entanglement.”

“MLA believes the federal government should apply the law equally among all sectors that might pose a risk to the endangered right whale and that its efforts have been disproportionately and unfairly focused on lobster fisheries,” said McCarron. “Addressing the threat posed by ship strikes with new rules and strict enforcement is an important and long overdue first step."

Oceana activists who have spotlighted speeding ships coming into U.S. container ports praised the proposed rule but want NMFS to do more.

“Today’s proposed rule shows that the National Marine Fisheries Service is serious about addressing a top threat to North Atlantic right whales, which are constantly at risk from speeding vessels,” said Gib Brogan, campaign director at Oceana. “It’s no secret that speeding vessels are rampant throughout North Atlantic right whales’ migration route, all along the East Coast.”

Brogan said his group wants NMFS to go farther in revising the speed rules by removing exemptions for government vessels, improving speed limit enforcement, and requiring vessels to carry AIS and keep the systems continuously transmitting for public transparency on shipping traffic.