Offshore wind projects off the East Coast could take up to a 15 percent bite out of the surf clam industry’s $30 million annual revenue, according to two new studies from Rutgers University researchers.

The biggest loss could be up to 25 percent for boats based in Atlantic City, N.J., a historic center for the fishery.

The paired studies, published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science, show how total fleet revenue may range from 3 percent to 15 percent, “depending on the scale of offshore wind development and response of the fishing fleet.”

The researchers developed a complex computer model to predict how the surf clam fishery may change in response to large-scale wind turbine arrays – such as the 1,100-megawatt Ocean Wind 1 project planned off Atlantic City.

“Understanding the impacts of fishery exclusion and fishing effort displacement from development of offshore wind energy is critical to the sustainability of the Atlantic surf clam fishing industry,” according to co-author Daphne Munroe, an associate professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences. Munroe and the research team worked closely with fishermen and the clam industry in developing the model.

“Tools that can predict and manage these complex and interconnected challenges are essential for developing and evaluating strategies that allow for multiple users of the offshore environment,” Munroe said in a project summary released by Rutgers.

The surf clam and deeper-water ocean quahog fisheries supply product for everything from canned clam chowder, to the ubiquitous fried clams of seafood restaurants and high-end sushi and sashimi.

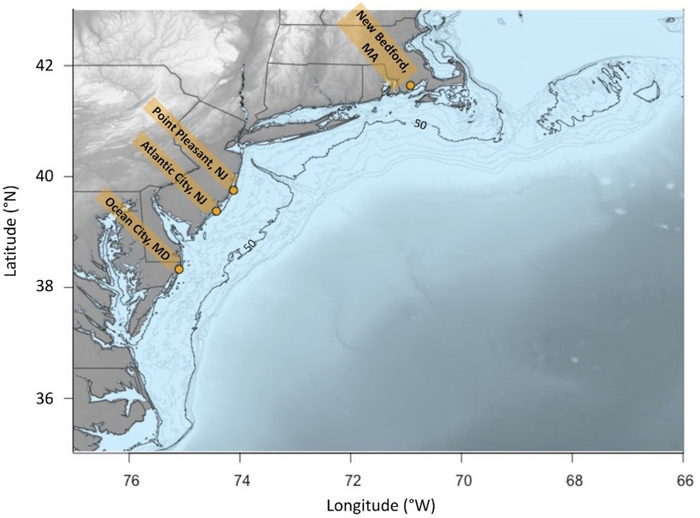

Surf clams sustain fishermen, boats and processing plants from Virginia to Massachusetts and generate more than $30 million in direct annual revenue, according to the study.

Clammers have long sought a 2-nautical mile wide spacing between turbine towers, which they say is essential for safely operating their heavy gear of hydraulic dredges that gather clams off the sea floor.

But in a newly released draft environmental impact statement, BOEM says reducing turbine arrays to that spacing would cut down the turbine layout plan by two-thirds and make the Ocean Wind 1 project unable to fulfill New Jersey’s renewable energy plan.

The surf clam fishery is already under pressure from the effects of climate change on U.S. Atlantic waters, with catch rates declining and the resource shifting northward.

The business took a beating in 2020 during the covid-19 pandemic when restaurant closures slashed demand for clams, and ex-vessel value purchased by seven major processors plunged from $28 million in 2019 to $23 million.

To measure the potential impacts of offshore wind farms on Atlantic surf clam catches, the researchers built the Spatially-Explicit Fishery Economics Simulator (SEFES), a computer model to help create a comprehensive picture of stock dynamics, the fishery and fishing fleet decision-making.

“SEFES is basically a virtual world that allows us to simulate the dynamics of the fishery – from how captains navigate their boats to how weather impacts the catch,” Munroe said. “But the model also has a layer of biology, which accounts for the clam populations and how they change over time and in space.”

That includes factoring how climate change is already pushing clam distribution northward.

To fine-tune SEFES, Munroe and colleagues worked closely with the industry, including fishermen who provided feedback. “We showed them how the model was working, and they told us if our assessments were right or wrong,” said Munroe. Input from fisheries managers and data from landings were also used to ensure the model was working well.

With the model calibrated, Munroe’s team then sought to predict the impacts of future wind farms on Atlantic surf clam catches. As of 2021, some 1.7 million acres of ocean have been leased for offshore renewable energy projects on the outer continental shelf.

Atlantic surf clam vessels that fish these areas must operate within restricted lanes or in ways that may be less efficient than in unrestricted areas. These changes to fishing behavior will have costs that SEFES can calculate.

“If fishermen can’t fish in wind-leased areas, they will fish elsewhere in locations that might be less than optimal, changes that will mean longer trips and potentially smaller hauls,” said Munroe.