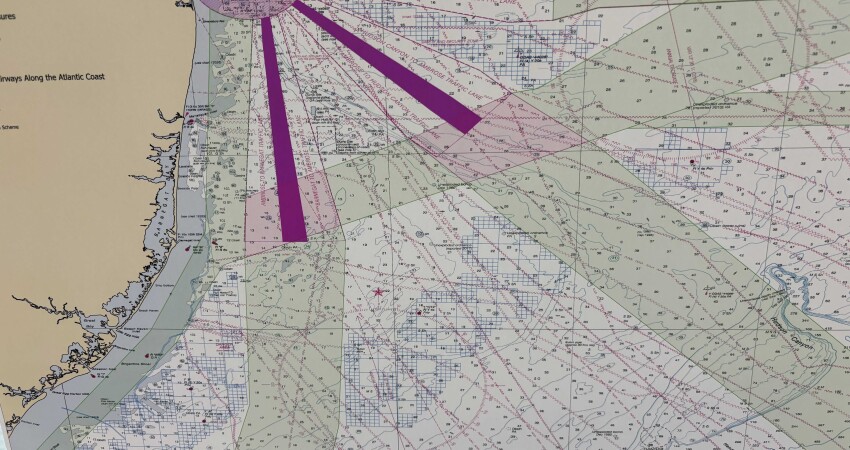

Seven years into its planning, the Coast Guard’s effort to develop safe fairways for vessel traffic near East Coast wind turbine arrays still has mariners uncertain of how offshore wind energy development will affect traditional shipping and fishing industries.

In January, the Coast Guard published its latest version of the detailed plan and recently extended the public comment period to May 17.

At the request of Rep. Jeff Van Drew, R-NJ – whose opposition to offshore wind development reflects stiff resistance in his coastal New Jersey district – Coast Guard officials held a public hearing at Richard Stockton University Wednesday.

“It’s very unclear to us whether insurers will allow us to work or transit around offshore turbine arrays,” said Scot Mackey of the Garden State Seafood Association. From the start of planning by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, commercial fishermen sought defined transit lanes through wind energy areas and 2-nautical-mile spacing between turbine towers for safety but were rebuffed, said Mackey.

Tug and barge operators see fairways as essential for coastal shipping and wind energy to co-exist, and the Coast Guard’s goal of 9-nautical mile offshore lanes. But two fairway connections – Cape Charles off Virginia and the New Jersey to Delaware Bay connector – could be constrained by shoals that effectively narrow their routes and could be reconfigured, said Brian Vahey of the American Waterways Operators.

About 30 people attended the Coast Guard hearing – far fewer than at BOEM public sessions on the Atlantic Shores proposal for a turbine array off the Long Beach Island and Brigantine beach resorts on the New Jersey shore. They talked of their concerns about the impact on the Coast Guard’s search and rescue missions, fishing, and vessel traffic.

“There are many ways vessels can go down, and they don’t go down in bright sunny weather,” said charter fishing captain John Howard. He worries that the documented effects of radar interference from rotating turbine blades will make it hard for captains to see other vessels and for the Coast Guard to find them in emergencies.

“If we drift into these areas (turbine arrays), you guys will never find us,” Howard told Coast Guard officials. “If you can’t find us, you’ll never save us…you guys are our main line of defense.”

In Congress and the news media, Van Drew has kept up a drumbeat of opposition to offshore wind that contributed to Ørsted’s Oct. 31 decision to abruptly withdraw from its flagship Ocean Wind 1 project near Atlantic City.

However, the company still holds its lease for the area from BOEM. If the leases granted by the agency are developed, they would be “the largest industrialization of the ocean in history,” said Haddon Antonucci, policy director for Van Drew’s office.

Antonucci said BOEM began designing wind energy areas before the Coast Guard’s first East Coast port access study of 2017. Noting ongoing legal challenges to federal permits for offshore wind development, Antonucci contended BOEM had effectively preempted the Coast Guard and other federal agencies.

“BOEM gave the Coast Guard this situation, and they have to deal with it,” said Antonucci.

Plans for the Atlantic Shores project and other leases will limit access for New Jersey fishermen based in Barnegat Light, Atlantic City, and Cape May, said Mackey of the Garden State Seafood Association.

“For scallop fishing, it’s a 24-hour clock,” said Mackey, referring to day trip limits mandated by National Marine Fisheries Service rules. If fishermen lose time because they must make long transits, they lose fishing time and money.

Captains warned that displacing fishermen from traditional grounds can lead to traffic and gear conflicts. Mackey said they also worry about the long-term loss of fish and shellfish habitat.

“We can’t fish over structure. We fish on sandy bottom,” said Mackey. Even after decommissioning and removal after an expected 30-year service life, offshore turbines would still leave behind a footprint of artificial reefs, with rock scour armor on the sea floor.