Preston Dore is used to riding out the hurricanes that have blown through his town of Delcambre, La., about 100 miles west of New Orleans. For the last 40 years, he and the boat have always walked away, relatively unscathed. Hurricane Ida was different.

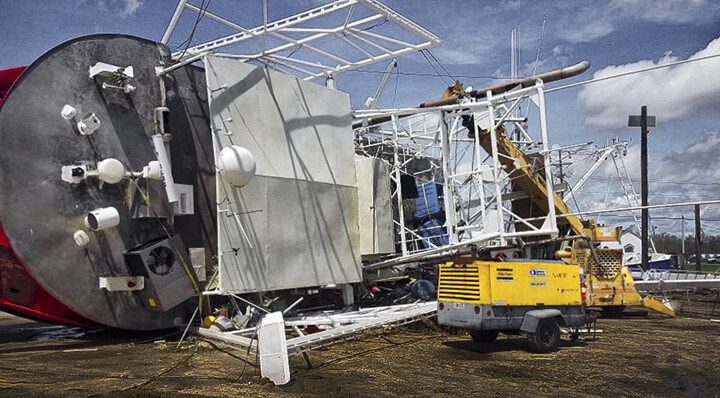

Unlike other storms, Dore had to ride this one out shoreside. His new boat, the Demi Rae, was up on blocks at the Gulfbound Shipyard in Chauvin, La., in the final stages of a five-year building process.

Hurricane Ida made landfall near Port Fourchon, La., on Aug. 29, the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. When the storm hit at near-category 5 strength, most local fishermen had done what they could do to prepare in a hurry. The storm had gathered strength quickly as it crossed the Gulf of Mexico, and the surge sent the hurricane ripping through coastal areas with winds gusting up to 172 miles per hour, devastating the town of Grand Isle, south of New Orleans, and taking out critical infrastructure across the region.

“Every time we have something like this happen, we lose a significant part of the state’s seafood fleet,” said Julie Falgout, Louisiana Sea Grant agent. “Fishermen either can’t or don’t want to go back to the water. Docks and processors face similar issues. I know of one dock that will not rebuild after being completely destroyed.”

For Dore, things are not looking good. Hurricane Ida may have cost him his boat, his livelihood, and his ability to provide for his family.

“I put my life savings and even recently had to sell my rental properties, my only income, to finish this vessel. I was on last stage of finishing her, which was redoing the bottom,” Dore wrote in a text to Falgout. “She got severely damaged and lays on her side. Looks like damages could exceed $200k, and I have over $500k invested with no insurance.”

Insurance is a rising cost industrywide, with business expenses complicated by changing regulations, shifting seasons, and difficulty finding reliable crew.

“Who can pay $25,000 a year for insurance and still make a living?” Dore said.“All I can do right now is pray for a miracle.”

Falgout noted that the Louisiana delegation is trying to fast-track disaster funds. The Gulf Seafood Foundation has put together a coalition of seafood and state organizations to try to help secure relief. But the damages are widespread and still being assessed in some cases, almost two months later.

The Gulf Seafood Foundation’s Helping Hands is accepting donations via PayPal.

“If he can’t get the money to repair his boat or sell it, he may have to sell it for parts or scrap,” Falgout said. “That’s a hard thing for any fishermen to say.”

The region’s fishermen and seafood industry are seeking all options for help to get back up and running.

“We need an improved ‘Back to the Dock’ program that was devised after Hurricane Katrina,” Falgout said. “And a hell of lot of private philanthropy.”

Word was slow to come out of the small fishing ports of Louisiana. Between power outages and road closures, travel and communications were hampered for a full month.

“A majority of the boats made it through the storm,” said Montegut fisherman Lance Nacio. “But the seafood communities’ infrastructure and homes have been severely damaged.”

Oyster farmers on Grand Isle lost their entire crop. Processing facilities from Grand Isle to Dulac lay in ruin, and almost 30 percent of the shrimping fleet in Golden Meadow was incapacitated at the start of the fall shrimp season.

“Here in Venice, we lost three or four shrimp boats. But over in Chauvin and Dulac, it is more like half that fleet,” said fisherman Acy Cooper.

Memories of Katrina are all too close, still, even 16 years later. Though Ida is the second strongest hurricane to make landfall in Louisiana, many locals are saying the damages are worse than the aftermath of Katrina, which holds the record as a Category 5.

“During Katrina, our organization, known then as Friends of the Fishermen, raised more than a million dollars to rebuild ice houses and other infrastructure, as well as people’s lives and communities,” said Gulf Seafood Foundation President Raz Halli. “The need is just as great now, if not greater.”

Recovering from that damage will take more than money, as these industry veterans know all too well.

“We need food, generators, fuel and of course ice,” said Cooper. “We also need more doctors and nurses, as well as mental health professionals, because as we learned after Katrina, storms like this take a mental toll on everyone.”

In the meantime, these communities and fishermen draw on each other for strength.

“Right now it is not about getting back to fishing,” said Jim Gossen, president and CEO of Louisiana Foods. “Right now it is about mending the lives of families so eventually they can fish again.”

The Gulf Seafood Foundation’s Helping Hands is accepting donations via PayPal.

Ed Lallo at Gulf Seafood News contributed to this report.