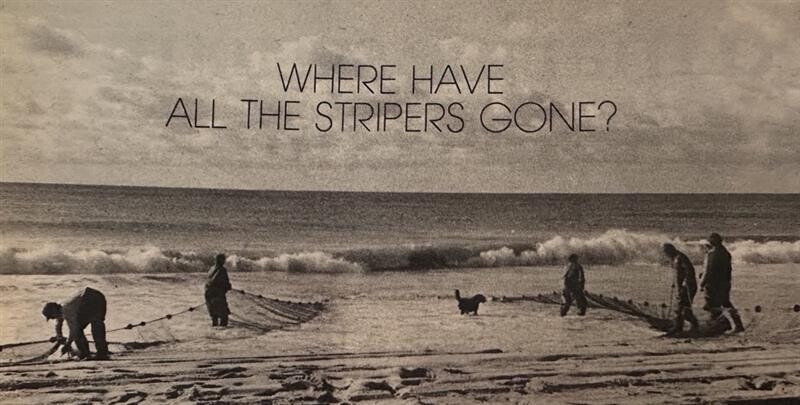

Fishing Back When: Story by Susan Pollack from the 1983 Yearbook of National Fisherman

One of the most commercially important fish species in the United States seems to be disappearing from the Atlantic seaboard.

The question, of course, is: Why?

A dramatic decline in East Coast striped bass landings during the past decade has now combined with three consecutive years of dismally low reproduction in the fish's major spawning ground, Chesapeake Bay.

This situation perplexes - and worries — scientists, fishery administrators and fishermen. Diminished catches may merely represent the ebb of a natural cycle that, some argue, has caused wide fluctuations in striped bass stocks since landings were first recorded in the 1880s. But scientists, among others, are increasingly concerned over threats to the species' habitat stemming from sewage and power plants.

Also considered dangerous are the seepage and runoff of toxic chemicals, heavy metals, fertilizers, pesticides, and other pollutants, and the draining, dredging, and filling of marshlands. Scientists likewise fear the long-term effects of increased harvesting pressure by both sport and commercial fishermen.

"From the early 1960s through the mid-1970s, when striped bass stocks were at a historical peak, the recreational catch [along the Atlantic Coast] was five times greater by weight than the commercial catch," according to Dr. John Boreman, a striped bass specialist at the National Marine Fisheries Service's (NMFS) Woods Hole, Mass., laboratory. Although the disparity is not as great today, Boreman says, "The recreational catch still exceeds the commercial."

Lately, debate has focused on implementing a pending interstate plan to manage the species. The recommendations were released in October 1981 following a four-year study by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. One proposal in particular has caused considerable controversy: a 24" minimum size for striped bass harvested in coastal waters. (A smaller mimimum would be allowed in certain bays and estuaries.)

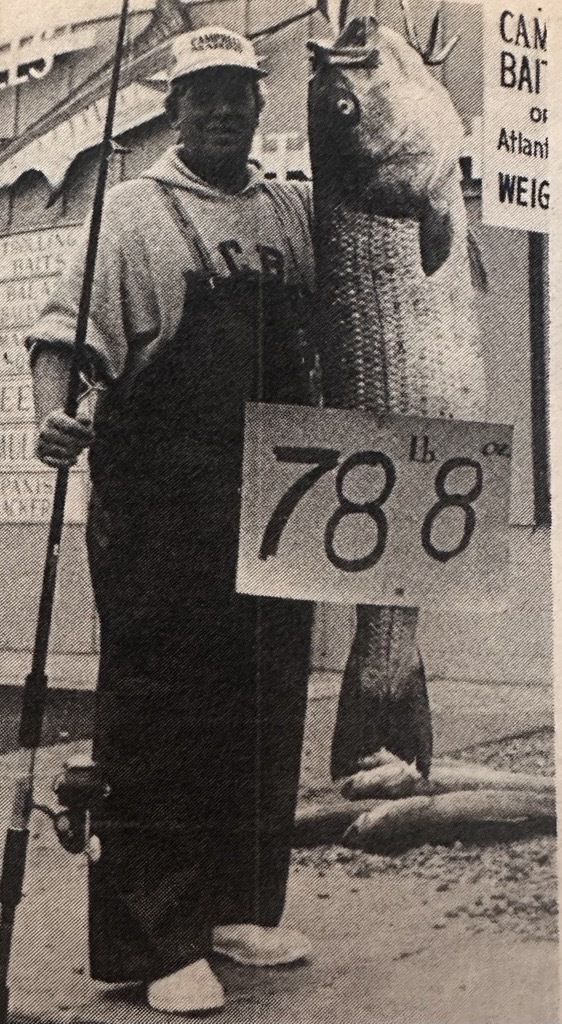

The recreational catch of striped bass has always exceeded the commercial harvest, and there are those who believe the quest for the larger, trophy-sized stripers is contributing to the decimation of high-quality brood stock. Some states propose establishing a maximum-size limit to prevent this from happening. Photo by Garcia Tackle

The striper's intelligence, resilience and ability to attain huge trophy size have been extensively celebrated in angling lore. In July 1981, the sport-fishing world was excited by the capture of a world-record 76-pounder off Montauk, L.I. That event was eclipsed last September when a lifeguard reeled in a 78½-pounder from the New Jersey surf. He was later publicly awarded $250,000 by a tackle manufacturer whose contest he had entered.

The Pollution Problem

While sport and commercial fishermen and fishery officials lock horns over regulations, the real culprit - pollution - is being ignored, contends Larry Simns, a third-generation Chesapeake fisherman and the president of the Maryland Watermen's Association.

As the watermen's spokesman, Simns has been fighting environmental battles for more than a decade and supporting grass-roots efforts to raise hatchery bass. He insists, "When legislators pass a law restricting harvesters and say they've done something, they're fooling the public." There are infinitely more questions than answers in regard to the cause of depressed striped bass stocks.

Scientists who have published tomes about the species (Roccus saxatilis) suggest that the decline probably results from a combination of factors rather than from any single problem. "Even among biologists, there is no consensus about what's happening," says Byron Young, a long-time striped bass researcher with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

The late of the bay's crab and oyster stocks is also getting attention. A $27-million, five-year study by the Environmental Protection Agency EPA) confirms what many Chesapeake watermen and scientists have warned about for years: Water quality in the bay is deteriorating (see NF Feb. '83)

Moreover, nearly a third of the bay is oxygen-deficient from late spring through scientists who worked on the staff of EPA's Chesapeake Bay program are now seeking to translate the findings of their 600-page report into governmental action.

Chafee introduced the amendment authorizing an initial $4.75 million for research and monitoring by federal agencies and 12 coastal states. Under the Chafee study, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service is performing contaminant research. NMFS, aided by scientists from Maine to North Carolina, monitors estuarine reproduction through surveys of eggs, larvae and juvenile bass.

The pattern of coastal catches by age and sex is also being cooperatively assessed. This research is painfully slow, but it is beginning to reveal links between contaminants in the bay and striped bass mortality and is also shedding some light on other factors of the striped bass dilemma.

A 1975 study by Texas Instruments, which is still regarded as "the handbook" in fishery circles, found that the Chesapeake contributed 90% to coastal stocks, the Hudson 7%, and the Roanoke River in North Carolina 3 %. New evidence indicates that the Hudson River may play a more vital role in contributing to the coastal striper population- particularly the population off Long Island and New England - than had been previously thought.

A key investigator, Dr. Webster Van Winkle of Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee, speculates that the Hudson may be producing as much as 20% to 30% of the striped bass caught off Long Island and New England. He attributes this to the river's relatively stable production at a time when the Chesapeake's is at an ebb.

During the peak production years of the 1960s and through the mid-1970s, Maryland, the primary producer of striped bass, also harvested the bulk of the catch. Virginia, North Carolina, Massachusetts, and New York followed.

Today, the same five states still harvest the lion's share, but Massachusetts and New York take a proportionately larger share than they did before, possibly indicating the influence of stable production in the Hudson and the decline in the Chesapeake.

In 1981, the last year for which complete commercial catch data are available, Massachusetts landed 737,000 lbs.; New York, 805,000; Maryland, 1,438,000; Virginia, 381,000; and North Carolina, 417,000.

By contrast, in 1973, when Chesapeake stocks were at a peak, Massachusetts landed 1,386,000 lbs.; New York, 1,741,000; Maryland, 4,976,000; Virginia, 2,888,000; and North Carolina, 1,752,000. A further decline in Maryland's landings in 1982 is cited as evidence of the recent slump in Chesapeake production.

Last year, landings plummeted to 430,000 lbs., a tenth of what they were a decade ago. Maryland DNR's Harley Speir points the finger at poor reproduction in the bay in 1979 and 1980 as the cause. He argues that Maryland's imposition of a spring spawning-area closure is not responsible for the sharp decline in 1982 landings, as others contend. The effects of the Chesapeake's even more dismal 1981 hatch may be felt this year.

An Endangered Species?

In January 1983, NMFS denied as unwarranted a petition from Stripers Unlimited, a Massachusetts sport-fishing organization, to have the Chesapeake strain of striper declared an endangered or threatened species. Yet, despite an improvement in striped bass reproduction in the Chesapeake Bay during 1982, concern continues over the future of that stock.

After climbing fairly steadily for more than a decade, commercial striped bass landings peaked at 14 million Ibs. in 1973 but have since sharply declined to slightly under 4 million Ibs. annually, representing a nearly 50-year low. In 1981, some 3.8 million ibs. were caught, the lowest catch recorded since the 1930s.

Maryland's annual seining survey deemed the most reliable barometer of future landings, revealed dismally low reproduction in the bay between 1979 and 1981. The index of young fish, which is watched avidly as a forecast of catches in the bay two to three years later and along the coast three to six years later, plunged from an all-time high of 30.4 stripers per haul in 1970 to 4.2 in 1979, 1.9 in 1980 and 1.2 in 1981.

Water temperature is also crucial to survival and food availability. Apart from the weather, a joint effort by Maryland's NR and Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to reduce chlorinated sewage effluent entering Maryland's spawning areas by 66% may also have contributed to the improved hatch, observes DR's Speir. Discharges of chlorine, a biocide suspected of killing striped bass larvae and the aquatic organisms they feed on, was reduced at 40 Maryland sewage treatment plants. This was achieved with little effort and a total cost of only about $50,000.

As their plan clearly states, "Survival during this stage determines the number of fish that will be recruited into the fishery." This appears to be confirmed by egg and larval trawl surveys conducted during the past three years in Maryland's Choptank River by Boone and Jim Uphoff of the DNR. "In 1980 and 1981,” Boone says, "the eggs hatched, and then several weeks later, when the larvae were feeding, great numbers disappeared. From one week to the next, we lost as much as 80% to 90% of the fry. The loss occurred three to four weeks after the hatch." Although data from 1982 have not been fully tabulated, the difference was obvious, reports Boone. "The fingerlings were far more numerous."

The effect of contaminants upon larval striped bass is now being investigated under Chafee funding by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Columbia National Fisheries Research Laboratory in Columbia, Mo., with help from NMFS' Narragansett, R.I., laboratory. According to Dr. Paul M. Mehrle, who heads the research, "No single contaminant has been identified as responsible for the decline of East Coast striped bass stocks."

Tackle manufacturer Robert Pond of South Attleboro, Mass., whose fellow Stripers Unlimited members filed the endangered species petition, had earlier complained that research was ignoring the single most important area of investigation: the viability of the eggs themselves. When the Johns Hopkins project was approved for Chafee funding on March 25, he called it "a step in the right direction."

The Interstate Plan Randy Fairbanks, chairman of the interstate plan's scientific and statistical committee and assistant director of the Massachusetts Division of Marine Resources, says plainly, "We cannot manage meteorological events, and we're in a difficult position to effect short-term solutions relative to contaminant loads or other issues of habitat viability. But with stocks very depressed, we must do the only thing we can: control exploitation." By that, Fairbanks means fishing pressure.

By increasing size limits and thus delaying harvest, the plan's adherents hope to sustain the fishery by spreading a given year class over a longer period. Meanwhile, the federal government, which financed the interstate plan (in which scientists, fishery administrators, and citizens participated), has taken an increasingly hard line. Last year, U.S. Rep. Gerry Studds of Massachusetts sought unsuccessfully to deny 50-50 federal matching funds for anadromous fish research to states that did not follow the plan's recommendations. These funds have been the mainstay of tagging efforts, seining surveys and stock assessments.

A substitute incentive was included in a package of amendments to the Fishery Conservation and Management Act that President Reagan signed into law in January 1983. It guarantees all states that have complied with an interstate plan for anadromous fish 90-10 matching funds instead of 50-50. Though NMFS has yet to issue a legal interpretation, some state officials fear political pressure on their research.

John Cronan, Rhode Island's Fish and Wildlife Division chief, says that depriving a state of needed research funds simply because it does not comply with all the plan's recommendations "is attempting to solve a problem by taking away a state's ability to solve it." Furthermore, he adds, just because Rhode Island has not complied with an across-the-board 24” limit does not mean it has not done its utmost to cooperate with the plan's intent. He reports that he informed other drafters of the plan that the across-the-board restriction would put many net fishermen out of business.

Allen Peterson, the Northeast regional director of NMFS, believes otherwise. "If the states did not think they could implement the plan, they should never have approved it," he declares. Though Uncle Sam cannot force the states to adopt the plan, since the striped bass are found within their three-mile territorial limits, the government does control funding, he points out.