The last time this column had an update on A.C. Fisher Jr. Marine Railway at Wicomico Church, Va., was in the June 2002 issue. It is refreshing to note that nothing much has changed at the yard, as the railway still hauls about 30 boats a year on the larger railway and maintains the Virginia Marine Resource Commission’s small-boat fleet on a smaller railway. The yard is as traditional as any yard in the South.

In January, the 41-foot wooden deadrise workboat Nassawadox was up on the rails getting a new horn timber. In wooden boat construction the horn timber ties the keel and transom together, with the propeller shaft running through the horn timber and skeg. A horn timber shapes a concave bottom near the stern. When the boat is underway, a concave bottom helps to keep the stern down, just touching the water, and aids the boat in staying level in the water. A solid-piece horn timber is a tricky element to replace.

Andy Sisson of Mila, Va., is installing the horn timber. The owner of the yard, Junior Fisher, says Sisson is a master boat carpenter. Whenever there is a major job to do on a wooden boat at his yard, Sisson is called in.

Amazingly, Fisher uses very little purchased milled lumber, as he goes out into the Northumberland County, Va., forest ever year to purchase and cut down five spruce pine and a couple white oak trees. He has it milled locally for boat lumber. Fisher says out of the five pine trees, he is lucky to get three that can be used for boat lumber because of the disease red heart. The two unusable trees are milled and sold for house lumber.

Red heart or “red ring rot” is a disease that ruins the tree for boat lumber use. “We can’t tell which trees have it until we cut it down,” says Fisher. Red heart is a disease usually found in mature pine trees where the heart of the tree is infected by the fungus Phellinus pini.

“The areas along the red colors in the heart of the tree are very susceptible to rot,” says Fisher. “The infected wood is fine to use as house lumber in places where water doesn’t touch it. I have it milled and sell it to house builders who come by.”

The new horn timber in the Nassawadox is shaped from a 12" x 12" x 8' long spruce pine timber and came from a tree Fisher and Sisson cut several years ago and cured at the railway.

“Fifty years ago, boatbuilders could get good lumber from a local sawmill, but they did not have very good fasteners,” says Fisher. “Today we can’t buy good boat lumber and that’s why we cut our own, but we have great fasteners. If the old wooden boats had had the fasteners we have today, they’d have lasted a lot longer.” The new horn timber is bolted to the keel with stainless steel bolts.

Fisher inquired about his old friend and boatbuilder Willard Norris. “We worked together at VMRC. And when I had a problem here that I couldn’t fix, I’d call him and he’d talk me through it,” he says.

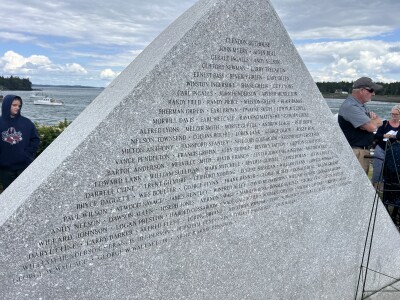

Willard Hamilton Norris, 94, passed away on Jan. 7, the last active traditional wooden boatbuilder in Deltaville, Va., where more deadrise commercial wooden boats have been built over the years than anywhere else on Chesapeake Bay.

Norris was born in 1927 in Deltaville to a traditional boatbuilding family. In fact, he had boatbuilders on both sides of his family. His grandfather, Ed Deagle, built deadrise boats on the shoreline at his home on Jackson Creek where Willard was born. His uncle Pete Deagle, repaired log canoes next door. Willard learned the trade by helping his uncle Alfred Norris at his yard “across the road.”

Norris later went on to work for his uncle Lee Deagle at Deagle and Son Marine Railway. Deagle’s was a melting pot of wooden boatbuilding knowledge. The yard employed former log canoe and deadrise boatbuilders, many working there between boat orders. On the side, Norris was building traditional wooden boats.

One day, Norris got an offer to work for the Virginia Marine Resource Commission in charge of maintaining boats. After retiring from the commission, he continued to build boats and run fishing parties. Over his career, Norris built more than 100 deadrise boats and was still building deadrise and flat-bottom skiffs in his shop at the age of 91.

Fisher had not heard that Norris had died. On hearing the news, he blurted out “Willard is dead! Damn!” He briefly spoke of his appreciation for Norris and told Sisson, “I’ve got to go inside. I got to go in and think about Willard.”