A salmon packer met its fate off the coast of Wrangell, Alaska, in 1908, leaving behind a mystery and more than 100 souls trapped onboard

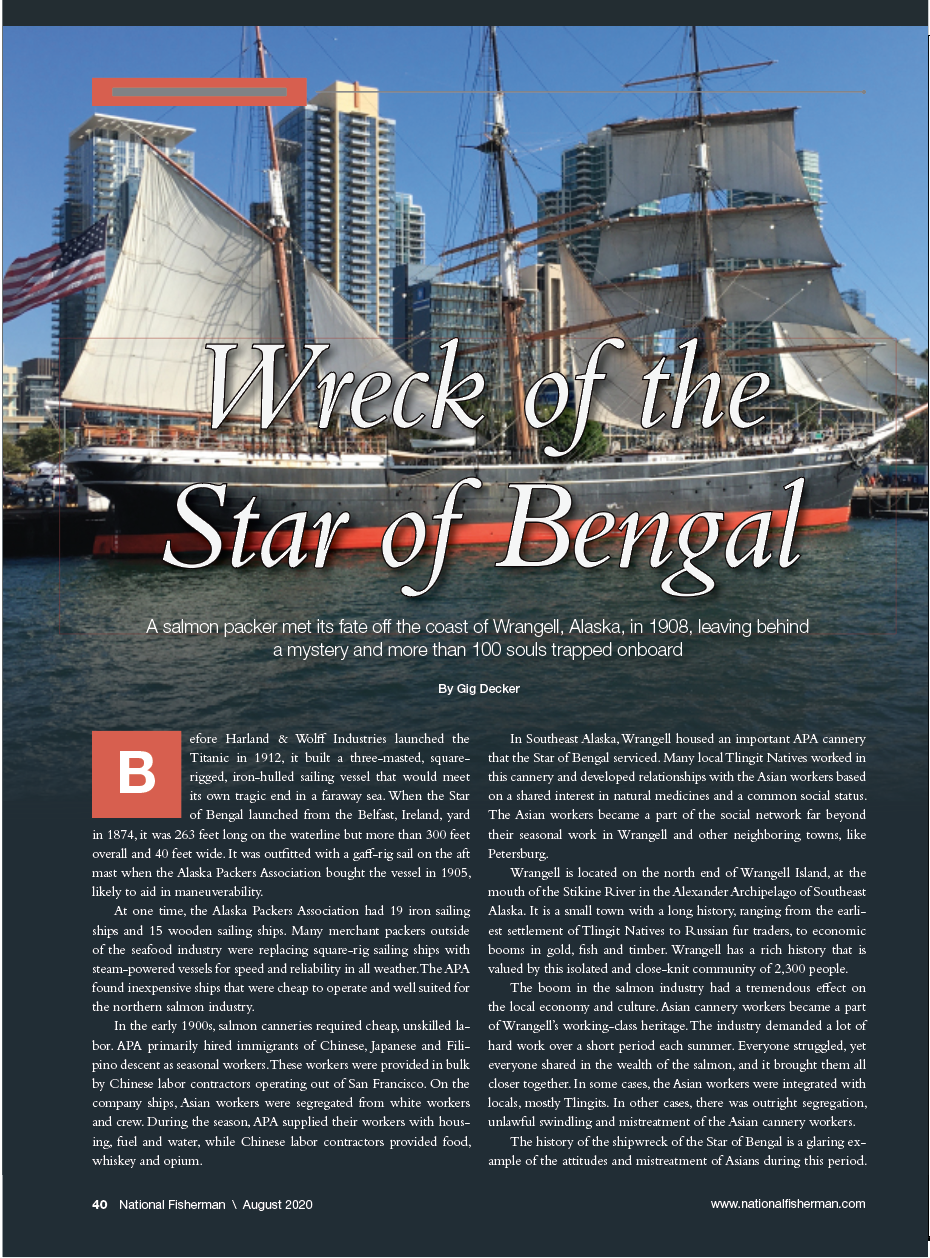

Before Harland & Wolff Industries launched the Titanic in 1912, it built a three-masted, square-rigged, iron-hulled sailing vessel that would meet its own tragic end in a faraway sea. When the Star of Bengal launched from the Belfast, Ireland, yard in 1874, it was 263 feet long on the waterline but more than 300 feet overall and 40 feet wide. It was outfitted with a gaff-rig sail on the aft mast when the Alaska Packers Association bought the vessel in 1905, likely to aid in maneuverability.

At one time, the Alaska Packers Association had 19 iron sailing ships and 15 wooden sailing ships. Many merchant packers outside of the seafood industry were replacing square-rig sailing ships with steam-powered vessels for speed and reliability in all weather. The APA found inexpensive ships that were cheap to operate and well suited for the northern salmon industry.

In the early 1900s, salmon canneries required cheap, unskilled labor. APA primarily hired immigrants of Chinese, Japanese and Filipino descent as seasonal workers. These workers were provided in bulk by Chinese labor contractors operating out of San Francisco. On the company ships, Asian workers were segregated from white workers and crew. During the season, APA supplied their workers with housing, fuel and water, while Chinese labor contractors provided food, whiskey and opium.

In Southeast Alaska, Wrangell housed an important APA cannery that the Star of Bengal serviced. Many local Tlingit Natives worked in this cannery and developed relationships with the Asian workers based on a shared interest in natural medicines and a common social status. The Asian workers became a part of the social network far beyond their seasonal work in Wrangell and other neighboring towns, like Petersburg.

Wrangell is located on the north end of Wrangell Island, at the mouth of the Stikine River in the Alexander Archipelago of Southeast Alaska. It is a small town with a long history, ranging from the earliest settlement of Tlingit Natives to Russian fur traders, to economic booms in gold, fish and timber. Wrangell has a rich history that is valued by this isolated and close-knit community of 2,300 people.

The boom in the salmon industry had a tremendous effect on the local economy and culture. Asian cannery workers became a part of Wrangell’s working-class heritage. The industry demanded a lot of hard work over a short period each summer. Everyone struggled, yet everyone shared in the wealth of the salmon, and it brought them all closer together. In some cases, the Asian workers were integrated with locals, mostly Tlingits. In other cases, there was outright segregation, unlawful swindling and mistreatment of the Asian cannery workers.

The history of the shipwreck of the Star of Bengal is a glaring example of the attitudes and mistreatment of Asians during this period. There are curious discrepancies between legal testimonies about the sinking and investigations of the wreck site. These discrepancies eventually helped remove the focus of the responsibility for loss of life from the captain and first mate of the Star of Bengal. This, in turn, played the much more significant role of removing the Alaska Packers Association from legal responsibility for the cannery workers and their families.

Sept. 19, 1908, marked the end of the Southeast salmon season. The Star of Bengal, captained by Nicholas Wagner, was the last ship sailing south to San Francisco from the Wrangell cannery.

These types of ships normally had three holds that could carry 85,000 cases of salmon. However, the Star of Bengal was carrying 52,000, which provided room in the forward hold to house the 111 cannery workers. It was common for the cannery workers to construct accommodations in the forward hold for the long voyage. Positioning the weight of the canned salmon in the midship and stern also provided an advantage of lifting the bow in heavy approaching seas.

As the Star of Bengal left Wrangell, it was towed by two tugboats to the outer coast, where the sails could be lifted. By law, the responsibility for the ship was in the hands of the tugboat captains until they reached a line that intersected the western shores of all the outside islands along the coast, which allowed the heavily laden ship to sail safely on its own.

The Chilkat was the preferred tug, but it was unavailable that day. The Hattie Gage and the Kayak, neither of which was large enough to perform the operation individually or even designed for vessel towing, were assigned the task. The Hattie Gage was under command of Capt. Erwin Ferrar, who had 35 years of experience at sea, including 13 seasons in Alaska. The Kayak was under command of Capt. Patrick Hamilton, who had recently obtained his captain’s license after 10 years of experience as a mate.

Ferrar was in charge of the operation. The small flotilla left Wrangell at 8:20 a.m., making about 5 miles per hour and planning to reach the open sea near Warren Island in 12 to 18 hours. They reached the 5.8-mile-wide strait between Coronation Island and Warren Island at 10 p.m. By that time, the wind had strengthened, and the visibility was compromised by rain, waves and darkness. The lookouts on both tugs could no longer see the Bengal, which was 250 yards behind them.

Somewhere between Warren Island and Coronation Island, the weather quickly became unmanageable. The cannery workers became agitated and were locked under the forward hatch to allow the crew to carry out their duties on deck. Then the Kayak became disabled. The option of turning around was suddenly lost. Ferrar on the Hattie Gage made a decision to get the Bengal into a safe anchorage on the east side of Coronation Island, in the vicinity of what is now known as China Cove. The anchor went down, and the Hattie Gage cut loose from the Star of Bengal. With the seas rolling in hard and the dim view of rocks and breakers all around them, it must have been a frightening ordeal for all three vessels. The Star of Bengal eventually broke up on rocks and sank. Of the 111 cannery workers onboard, 110 died, along with the lone crewman who had attempted to free them from the locked hold.

Fast-forward 100 years. Cliff James was an accountant in Wrangell who very much wanted to become a commercial harvest diver. Volney Smith, a fellow commercial harvest diver, and I had a lot of commercial experience and were avid historic divers, concerned with the looting of significant marine artifacts.

I have been an Alaska commercial fisherman for 46 years and harvest diver for 37. I am not an expert on shipwreck diving, nor do I see myself as an amateur underwater archaeologist. I am simply a guy who has been underwater for thousands of hours and seen thousands of miles of coastline along the Pacific.

I have seen many unusual and interesting things underwater, but none as fascinating as shipwrecks. They are historical artifacts suspended in their last moments. Shipwrecks that are also burial sites take on a much deeper meaning, a tangible reminder of the frail nature of life. Folks who live in coastal communities like Wrangell know many stories of tragedies at sea, and many of us have been touched personally by them.

James made a deal with Smith and me. He would establish a nonprofit organization focused on shipwreck preservation, and we would train him in commercial diving.

We set out to Coronation Island to find the Star of Bengal, our first record for preservation. We intended to record and describe the location and report it to the National Park Service, which has jurisdiction over all nearshore historic artifacts in cooperation with the Alaska State Office of History and Archeology.

The weather was perfect. We could nose in and out of the little niches through the numerous pinnacle rocks to look for the Star of Bengal in the calm and flat seas above Helm Point. We looked extensively around China Cove and found nothing.

As it happened, a friend who lives in the back bay of Port Protection had found a deadeye while beachcombing above China Cove. It was one of a pair that together would have been used to tighten down the spars on the sides of the square-rig sails. It was obviously from a large sailing vessel.

The deadeye had been stuck upside-down at the head of his garden on a hill looking out down Sumner Strait, where it turns from east-west to a southerly direction another 50 miles to Warren and Coronation islands and eventually the open sea. That was where we found the Star of Bengal. If you could see through the fog and mist, you could see the wreck site.

The confusion about where the ship went down was understandable, because the description of the site by survivors looked very much like China Cove: its crescent shape, the reef extending outward from the north end, and the knoll at the north end where the survivors rested until a rescue tug came for them. This is the reason later salvage crews were unsuccessful.

I was fortunate to be the first diver to the bottom to confirm the site. Drifting down through the green-gray hazy water, the first thing I saw was the anchor chain. I was immediately taken by the size of the links. They were enormous. I followed them north to the bow of the wreck, which to my surprise was fairly well preserved with the capstan for hauling the large anchor clearly in the middle of the deck.

The view from underwater tells an interesting story. The anchorage in which the Star of Bengal lies is a crescent cove with a reef off the north with a 50-foot rock at its end. This rock is very round and looks strange there. The cove has a sand and gravel bottom, which appeared to be a good bottom for anchoring. The anchor is in the south end extending north to the wreck just offshore, at a depth of approximately 70 feet, with the end of the reef and large rock just adjacent to it. The first third of the ship is easily recognizable. It appears that the ship swung to the east and broke on the rock.

The wreck lies bow pointing west, with the stern to the east. Broken on the large rock, the remaining two-thirds of the ship lies east of the rock, down a steep ledge, at a depth of approximately 140 feet. The bow is in fairly good shape though flattened out a little.

The captain and mate’s quarters were in the stern in approximately 140 feet of water. This is where any valuables of the crew and cannery workers would have been stored. We never attempted to explore this part of the ship, as we were not prepared to dive to this depth. The bank that the stern of the ship slid down looked very challenging, so we left this for later planning and exploration.

The captain of the Bengal charged the tug captains with cowardice by abandoning them and failure to perform their duties to the ship. He claimed that the captain of the Hattie Gage pulled the Bengal into an unsuitable anchorage and cut them loose before the crew of the Bengal was prepared. Wagner then claimed the Bengal dragged anchor across the small cove, dashing them upon the rocks before they could free the cannery workers locked in the hold — although the entire crew got to shore safely, and 110 cannery workers drowned. One man from the hold survived, and the only crewman who died was the one who went back onboard to let the cannery workers out. When the captain of the rescue tug arrived the next day, he ordered the crew to bury any white people who had perished.

The prosecution focused on the steam tugboat crews, even though there were two crimes, not one, that night: the allegations against the tugboat captains, and the lack of responsibility by the captain of the Bengal for the cannery workers’ deaths. Wagner, the captain of the Bengal, was later charged with neglecting the safety of the cannery workers, but it was soon dismissed.

Prior to the sinking, the crews of the three vessels had been through hours of distress. The confusion and sometimes reckless action of the crews must have added an intimidating aspect to Wagner’s perceptions that night. However, there appear to be a few discrepancies in Wagner’s testimony.

He claimed the tugs set the Bengal into the anchorage recklessly and cut the Bengal loose, though there has been reference to this site being used as an emergency anchorage during these frequent storms in this area. From my observations, it appears that the anchor was down in a reasonable place at the south end of the cove, and the chain ran adjacent to the beach. It looked like the ship had room in the cove to hold the bottom.

Wagner claimed the Bengal dragged anchor, and he and the crew needed to abandon ship without freeing the workers locked in the hold. The anchor is huge and is sitting on the bottom with no signs of dragging, as the flukes never dug into the gravel sand bottom. Four hours passed between when the anchor first went down and when the ship broke up. It is suspicious that the whole crew and captain could get to safety without attempting to free the cannery workers. Then there was the one crew member who did go back to free the cannery workers, only too late. Where were the captain and the first mate? Strange that this was not the focus of the entire inquiry.

Avoiding the responsibility for the abuses was accomplished by contracting with a Chinese middleman that would provide the labor and manage the canary workers while the APA’s only responsibility was to the Chinese middlemen. This buffered the APA from any abuses of the cannery workers. If anyone had a claim of mistreatment or injury, the APA could simply claim it was the responsibility of the Chinese middleman. Many times, the Chinese middlemen were found negligent and were simply replaced by another contractor.

The APA was powerful and had significant financial associations within Alaska. The legal proceedings did not ignore the crime of abandonment by Wagner. He was charged, but soon exonerated. If Wagner had been convicted, the APA would also have faced serious legal action. The focus of the proceedings was on the actions of the tugboat crews. APA also had an economic incentive to shunt responsibility to the deceased workers and their families. I believe respect for our history and the people who shared it necessitates future investigation.

The wreck is protected by federal and state laws under the National Park Service and the Alaska Office of History and Archeology. Together, they have jurisdiction over nearshore marine artifacts. There are very specific steps involved in the exploration and possible restoration or recovery of wreck artifacts. Federal and state laws account for the possibility of losing artifacts through time and allow consideration for recovery of these treasures.

The first step to future exploration and preservation of this shipwreck is to revisit the site and establish GPS coordinates of the wreck itself. Then survey the site for a description of the area, wreck and debris piles. Next, establish a safe anchorage away from the wreck for future exploration. At that time, state and federal underwater archeologists could examine the wreck and suggest alternatives to the historic record, and possibly allow reasonable artifact collection for the Wrangell museum. For example, the anchor is very large, ornate and beautifully tooled.

The Chinese civilization has produced some of the most impressive seafarers and adventurers ever known to the world. It is a wonder that these people would sail halfway around the world to toil in strange places and land in our little town of Wrangell. The fact that some of them could find themselves in such lowly circumstances, so disrespected, in Alaska’s historic salmon industry really touches a chord deep down in many of us who value the various cultures we cherish in Wrangell.

I hope to see further investigation into the shipwreck of the Star of Bengal and a monument placed here in Wrangell as a tribute to the Asian cannery workers who lost their lives on the wreck of the Star of Bengal.

Gig Decker is a longtime commercial fisherman and diver in Wrangell, Alaska.

Looking for more?

- Our FREE online membership offers access to our monthly digital edition, free reports, free quarterly magazine and discussion forums.

- For $14.95 a year, get all that plus access to our digital issue archives.

- For $15.95 a year, get all that plus the print edition of National Fisherman.