A captain’s decision to get underway while fatigued to make a salmon season opener led to the grounding and sinking of the seiner Tenacious near Whittier, Alaska, in summer 2021, according to a report by the National Transportation Safety Board.

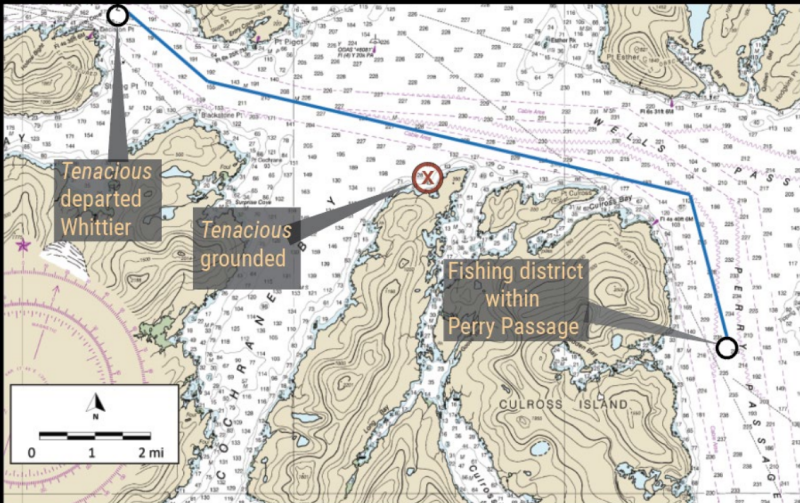

The 50.5-foot steel hulled Tenacious was making a night transit from Whittier to fishing grounds in Prince William Sound, when it strayed out of the channel in Wells Passage and grounded while steaming across the mouth of Cochrane Bay, according to the NTSB account.

The five crewmembers abandoned the vessel and were rescued by another fishing vessel, with one minor injury reported. The Tenacious later sank, a loss of $660,000 in vessel and gear, with 2,000 gallons of diesel fuel on board not recovered.

The captain told NTSB investigators he had fallen asleep in the wheelhouse, after being awake for nearly 20 hours previously. The Tenacious also had chart plotter and bridge watch alarms that, had they been activated, could have alerted the captain of impending danger, the board noted.

The crew had arrived in Whittier late in the evening of July 22 to try resolving maintenance issues with the Tenacious’ 20-foot skiff used to deploy its purse seine for pink salmon, for the season scheduled to open at 6 a.m. July 24. With repairs unsuccessful on July 23, three of the crew made a four-hour round trip to Seward to borrow another skiff for the trip; one deckhand told NTSB investigators the entire crew was operating on “not too much sleep.”

After making minor repairs to the borrowed skiff, the crew departed Whittier between 1 a.m. and 1:30 a.m. for a 3.5-hour trip via Wells Passage to Perry Passage near the south end of Culross Island, according to the NTSB narrative. As the crew slept, the captain took the wheelhouse watch.

The Tenacious struck rocks on an unnamed point west of Point Culross in the Chugach National Forest; the captain later told investigators he fell asleep. The impact awakened the crew and captain, who tried to back the vessel off the rocks, but the Tenacious started “going in circles,” according to the NTSB report.

The captain went to the engine room to investigate and saw flooding from holes in the forward bulkhead. He began to line up a bilge pump to try dewatering the space but had to get out when water began flooding from behind a live electrical panel.

The owner of the Tenacious was among the crew. He discovered the bunkroom flooding, went to the wheelhouse and broadcast a distress call at 3:26 a.m. on VHF channel 16 while the captain was below in the engine room. The owner instructed the crew to board the skiff to abandon ship and fetched the crew’s survival suits from the wheelhouse.

The captain went back to the wheelhouse, made a second distress call and joined the crew in the skiff; with all aboard the owner cut the tow line. The captain told the Coast Guard the skiff had fuel to get back to Whittier but was instructed to stay at the scene while a helicopter and motor lifeboat were being prepared for rescue.

At 3:36 a.m. the crew on the fishing vessel Grand Pa who had overheard the distress call advised the Coast Guard that all five Tenacious crew were safe on the skiff. The Coast Guard stood down its air and boat crews and the fishing vessel Wildlife arrived from Whittier at 6:42 a.m. to pick up the crew and skiff, returning to Whittier at 7:48 a.m.

The captain had operated fishing vessels for 32 years, and this was his second season as the Tenacious captain. It was the owner’s second season on board the vessel.

“The owner stated the crew typically got a ‘good night’s sleep’ during salmon fishing since the openers ended at 2000 (8 p.m.), after which the vessel delivered its catch to a tender and anchored for the night,” according to the NTSB report. “He also confirmed that, had they successfully repaired their own skiff (rather than making a 4-hour round trip by car to borrow another skiff), the crew would have sailed the Tenacious to the fishing grounds earlier and anchored overnight, instead of sailing early in the morning and arriving just in time for the opener.”

The crew usually slept from 10:30 p.m. until 4:30 a.m., but according to a deckhand, “the captain was awake all day on July 23. The captain slept 10 hours the night of July 22 but did not sleep between 0800 on July 23 and the grounding in the early morning hours of July 24,” according to the report.

The captain told investigators a pinched nerve had interrupted his sleep on previous nights, but he did not take any medication for the pain. Post-accident drug and alcohol tests for the crew were negative.

“Fishing vessels risk missing out on catch by not being on scene for openers,” the NTSB notes. “The captain told investigators the casualty ‘was my fault 100 percent. I knew everybody was tired and wore out and I knew I was too, but… I also knew there was lots of fish around, boat loads, so that probably had a lot to do with my decision.’ He also stated that the decision was his alone and that the company and owner would not fault him if he chose to stay in port.”

That aspect of the case – fishermen taking risks for season openers – prompted a longer discussion in the NTSB paper.

“The prospect theory of human decision-making proposes that human beings are more likely to accept higher levels of risk when faced with the perception of guaranteed future losses. In this case, the captain intended to fish on the July 24 opener because, as he stated, ‘there was lots of fish around,’” the report says.

“To avoid a perceived future loss, the captain’s risk tolerance was higher, resulting in the decision to get under way later than planned, during normal sleep hours, while in a fatigued state. With no specific quota for the catch, the Tenacious crew was limited only by its own ability to participate in the openers, which were scheduled based on dates and locations where pink salmon populations were plentiful.”

Other NTSB investigations into fishing accidents have uncovered that effect, when “the structure of this fishery encouraged working longer hours to increase the vessel’s portion of the catch, which leads to a fatigued crew,” the report says.

The NTSB noted other contributing factors. The wheelhouse had two electronic charting system that had saved tracks from past passages, and a cross track error alarm that could have warned the Tenacious was off course.

But the system was not on while the captain “was navigating by eye and did not use the route feature on the casualty voyage, stating, ‘I’ve done that route a thousand times,’” according to the report.

A bridge watch alarm could have alerted the captain in time to possibly prevent the grounding, but the key to activate that system had been lost so it was not active during the voyage.

The NTSB consistently pushes for stricter safety and construction standards for fishing vessels, and it makes that point in this latest report:

“Additionally, the Tenacious was not required by regulations to have watertight bulkheads; however, had the bulkhead between the bunkroom and the engine room been watertight, it would have contained the flooding.”