In 1936, the Libby 76 was one of thousands of double-ended sailboats gillnetting for sockeye salmon in the lucrative waters of Bristol Bay, Alaska. Today the 30-foot Libby 76 is one of only a few double-ended sailboats left, and it just completed a 300-mile journey back to Bristol Bay.

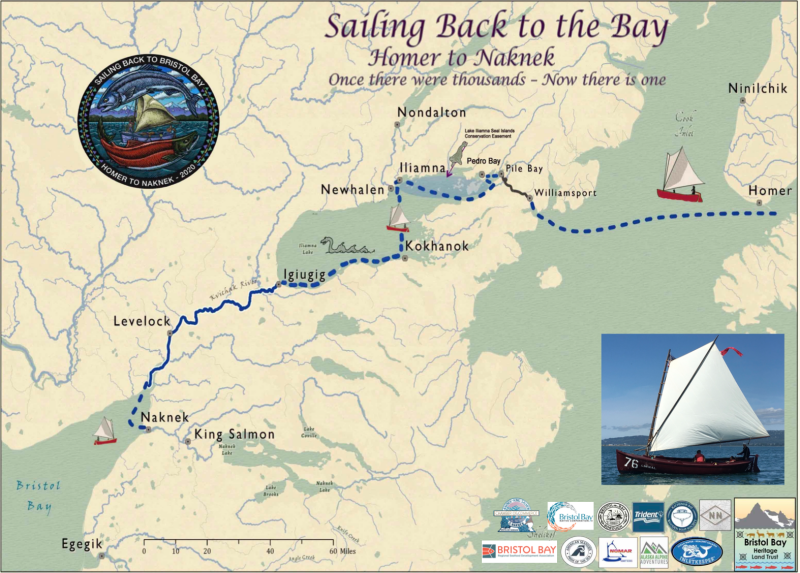

This was no ordinary journey. It included sailing 100 miles across Cook Inlet, portaging 17 miles over the Alaska Peninsula to Lake Iliamna, and sailing around to four villages before coming down the Kvichak River to Naknek.

At the same time of this historic adventure, over 75 million sockeye salmon were on their epic 1,000-mile journey to the spawning and rearing waters of Bristol Bay. Both journeys are remarkable in their own way.

To understand the salmon’s journey, I recommend watching the film, Mosaic, the Salmon Wilderness of Bristol Bay, which captures the salmon’s journey while explaining why Bristol Bay has become the icon of what we think about when imagining a sustainable fishery.

University of Washington fisheries scientist, Daniel Schindler, said in 2021, “During the last decade sockeye salmon returning to these [nine] rivers have smashed records that were thought to be unbreakable.”

At the time professor Schindler said this, the record stood at 71 million fish. Right now, the 2022 run of sockeye is at 76.5 million salmon with a harvest of 58.3 million sockeye. This level of extraordinary bounty comes courtesy of a vast mosaic of streams, rivers, lakes, and wetlands.

As Schindler, explains, “The reason Bristol Bay watersheds are so productive for salmon is largely because of the alignment of geologic, climatic, and ecological features that characterize the mosaic of habitats across this region,” Schindler explains. He says it’s this diversity that makes Bristol Bay sockeye more resilient to the year-to-year and decade-to-decade changes in the environment.

This sustainable fishery has been going on for 137 years. For the world, the Bristol Bay watershed is a shining example of what can be accomplished with a complement of diverse habitat, abundance-based management, and applied science. The boat is sailing back to Bristol Bay to honor this miracle of abundance, as well as its place in Alaska’s history.

Commercial fishing is Alaska’s premier industry. Alaska’s first cannery was established in 1878, twenty years before the iconic Klondike gold rush. Today the seafood industry is the number one private sector employer in Alaska. Bristol Bay alone provides over 15,000 jobs.

As an icon for the importance of commercial fishing in Alaska, the sailboat is a thing of beauty as seen in the historic photo below. The double-ender is a simple, sensuous construction of wood and canvas, a graceful but practical application of 19th century knowledge of wind and water to the ancient human endeavor of gathering fish.

Splendid and awe-inspiring is the view looking out at the double-ender. For those “iron men” who fished from them, the daily grind of living in an open boat was exhausting. Heavy linen nets with wooden corks were pulled by hand, the weather was wet more than not, and shifting sandbars were always waiting to take their toll on unwary fishermen.

As the Libby 76 sailed across the 77-mile-long Lake Iliamna, it stopped at four villages to give rides to kids so they could see how their grandfathers or great-grandfather fished. The kids got to put their hands on the tiller, and listen to the crew’s stories about the “sailboat days.”

The very day this sailboat left Homer was the 74th anniversary of a legendary disaster in the history of Bristol Bay. The tragedy occurred on July 5, 1948, during the peak of the sockeye run. Hundreds of sailboats were loaded with fish when a big storm with raging winds came in from the southwest, pushing many of the helpless boats into the shallows. Many boats were stranded and at least one fisherman, possibly more, drowned.

In the lore of Bristol Bay, that day became known as the “Bloody Fifth of July.” Fishermen used the incident to press for motorized fishing boats. Eventually, the federal managers of the fishery relented, and boats with engines were allowed in 1951.

The Alaska Territorial Board of Fisheries, formed in 1949, noted in its first report that while development in the territory was needed, it should not come at the expense of salmon, for salmon were Alaska’s “most important resource which, if properly cared for, will produce year after year.”

For Bristol Bay sockeye, that observation has proven true. The diversity of habitat available to Bristol Bay sockeye has not changed significantly for millennia. That variety has allowed sockeye to endure and evolve. Damage that diversity, however, and sockeye will become vulnerable - and no amount of good management will save them.

While Bristol Bay’s salmon habitat remains whole, it is now legally fragmented. The survival of sockeye and the commercial fishery is largely dependent on the willingness of its federal, state and Alaska Native corporation landowners to restrain themselves from activities on their lands that could significantly damage their habitat.

Before leaving the west end of Lake Iliamna, the Libby 76 sailed into Knutson Bay, one of the region’s most productive sites for lake spawning sockeye. It is also the site where any road to develop the massive Pebble Mine would be located. Even though the EPA has not yet finalized their decision on the Pebble Mine, there is a coordinated effort to block the road through the purchase of conservation easements on 44,170 acres.

The Pedro Bay Rivers project is a partnership between the Pedro Bay Corporation, the Bristol Bay Native Corporation, the Bristol Bay Heritage Land Trust and The Conservation Fund.

The project aims to place conservation easements on lands owned by the Pedro Bay Corporation, restrict development, and ensure the watersheds of the Pile and Iliamna Rivers and Knutson Creek continue to support the extraordinary returns of sockeye salmon year after year. The project needs to raise $20 million by the end of 2022.

As the Libby 76 approached the end of journey, the local gillnet fleet came out to greet the return of the double-ender. The crew soon learned that in honor of the last sailboat standing, the gillnet fleet chose to donate $1 million to help purchase these essential conservation easements.

If we give Bristol Bay a chance, it has the potential to adjust to climate change and to keep on being this immense provider of healthy protein.

In his closing comments for the film Mosaic, Professor Schindler says, “Of all the places to be optimistic about the health of salmon in a warmer future, we should believe that Bristol Bay is most likely to become a refuge from climate change.”

If you are a believer and lover of sustainable fisheries, please consider following in the footsteps of the local fleet. Click on conservationfund.org, search for Pedro Bay and then donate.

Kate Troll is the former executive director of United Fishermen of Alaska, former Fisheries Development Specialist for the State of Alaska and former fisheries director for the America's Office of the Marine Stewardship Council.