[Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect feedback from stakeholders.]

With four proposed alternatives on the docket to amend the management of halibut bycatch in Alaska’s Amendment 80 groundfish trawl fleet, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council voted Monday, Dec. 13, to approve a compromise between Alternatives 3 and 4.

“The preferred alternative balances the interests of the two largest halibut user groups in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands — the directed commercial halibut fishery and the Amendment 80 sector — by establishing abundance-based halibut [bycatch] limits for the Amendment 80 sector,” said Rachel Baker, deputy commissioner of the Alaska Department of Fish & Game, who devised and presented the compromise to the council.

The bulk of public comments called for significant changes, with many halibut stakeholders urging council members to support Alternative 4.

“While that would be a conservation and management action many in the public comments desired, I found it impractical at this time,” said Council Member Kenny Down of Alternative 4, which called for the deepest cuts to halibut bycatch in the A80 fleet, which harvests a variety of flatfish, rockfish, Atka mackerel, Pacific Ocean perch, and Pacific cod in the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands.

In the end, the council voted to manage the trawl fleet’s halibut bycatch based on abundance, not cut and dry hard caps, so all halibut user groups would be equally responsible for and responsive to shifts in abundance.

“While not as significant a reduction as was included in Alternative 4, the hybrid retains the existing bycatch limit at times of high abundance and reduces the bycatch limit by 35 percent below the existing limit at very low levels of halibut abundance — both substantial improvement over alternative 3,” Linda Behnken, executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association in Sitka, told NF.

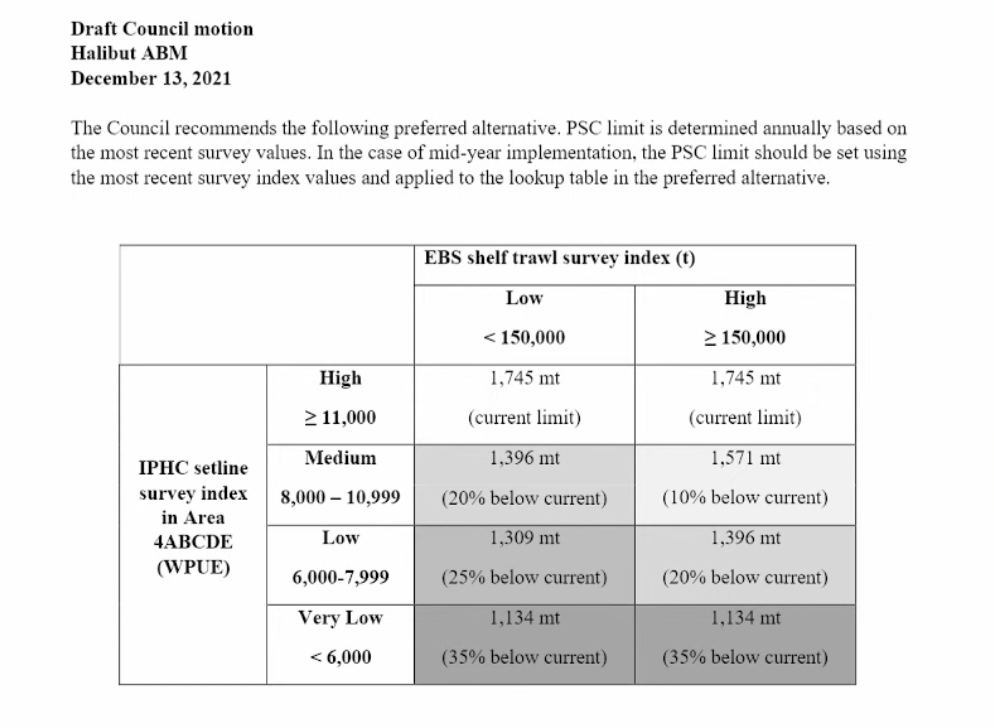

Baker’s compromise (illustrated in the graph below) combines input from the two abundance indices for the halibut fishery — the NMFS Eastern Bering Sea trawl survey and the International Pacific Halibut Commission’s setline survey. If the surveys reflect a high level of abundance, the current level of bycatch would remain in place. The cap would be reduced in kind with a reduction in surveyed halibut biomass.

“This abundance-based approach is much like the management approach for the directed commercial halibut fisheries off Alaska, which establish annual catch limits that vary with established measures of abundance,” Baker added.

In the meeting’s discussion and in public comments following the vote, council members and stakeholders have thanked Baker for her work in creating the compromise, which sought to strike a balance between managing bycatch for abundance and adhering to federal management standards.

“An imbalance was created as the bycatch users took an ever-increasing proportion of the available halibut, and the directed halibut fishermen bore the burden of conservation of the resource,” said Ray Melovidov, COO of the Central Bering Sea Fishermen’s Association and a second-generation halibut fisherman. “This action will result in the two user groups sharing that burden, and will better manage the resource.”

Trawl fleet stakeholders urged the council to approve the first alternative, calling for no changes to halibut bycatch, which does not decrease with reduced halibut abundance. They say significant bycatch reduction would likely push some fleet members out of business, would result in a dramatic reduction of wild domestic seafood in the marketplace, and is unlikely to improve the overall halibut biomass.

“We believe this action does not meet the standards of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, and we are exploring all options due to the unprecedented nature of this decision,” said Chris Woodley, executive director of the Groundfish Forum, a trade association that represents some members of the Amendment 80 fleet. “We are also concerned that the analysis shows that this decision will not result in the increases in harvest quota that the directed halibut fishery is looking for.”

However, reducing bycatch and boosting biomass are not always two sides of the same coin. The inequity the council is addressing with this motion is not as simple as who gets to catch the halibut but rather who shares in catch cap reductions when the biomass is low, given the Magnuson-Stevens Act’s call to reduce bycatch “where practicable.”

“Given all the factors that we have to consider, the motion does provide a balance to try to minimize bycatch at all levels of halibut abundance,” said Council Member Nicole Kimball, vice president of the Pacific Seafood Processors Association. “And it really at its core serves to fix the situation in which only halibut fisheries decline when halibut biomass declines. And it remedies this inequity in a way that I think is defensible under the Magnuson Act.”

Council members also spoke to their endeavors to answer to all of the National Standards in the Magnuson-Stevens Act, which address bycatch, community participation in fisheries, allocations and the best available science, among other factors.

“We are balancing multiple national standards,” said Council Member Cora Campbell, president and CEO of Silver Bay Seafoods, emphasizing the council’s responsibility to adhere to multiple, complicated and sometimes conflicting requirements. “All at once, we’re trying to achieve OY (optimum yield), allocate fishing privileges equitably, provide for sustained participation of fishing communities, and minimize bycatch to the extent practicable. And as difficult as that is, I believe that this motion strikes the appropriate balance and meets all of the national standards.”

With an array of national standards on one side and a complicated biomass with a vast range of user groups on the other, council members were pressed to thread multiple needles in creating a final motion.

“This council regularly tackles difficult issues, and this topic has consistently been one of those really challenging ones, given the large number of variables that impact halibut management,” said Baker. “The process to develop this ABM program reflects the difficulty of addressing a broad diversity of fishing industry, community and tribal interests that we’ve heard about throughout this process and are reflected in our analysis.”

Council members also acknowledged that the cuts would result in some hardships for the trawl fleet.

“The Amendment 80 fleet may have to forego some amount of profitability to reduce halibut mortality,” said Down. “Real efforts to reduce bycatch are net negative for all fisheries initially.”

But hardship alone is not a reason to abandon the call for bycatch reduction where it’s practicable, as is the call of National Standard 9.

“There is a balance in all industrial [regulation] in this world of natural resources between conservation and profit,” said Down, who also acknowledged benefits provided by the catch of the Amendment 80 fleet.

The shift to an abundance-based management program for groundfish bycatch has also resulted in an abundance of attention from Alaska’s coastal communities and fisheries stakeholders, who have been more engaged on social media and in virtual council meetings as a result of pandemic-induced lockdowns and familiarity with virtual meeting technology.

“Public engagement and the public testimony and advocating for positions on issues like this one are a cornerstone of the council process,” said Council Member Andy Mezirow, a charter fishing captain in Seward, Alaska.

Mezirow went on to caution that while public engagement is critical to the process, the level of discourse should remain fact-based and professional.

“On this agenda item at this very meeting,” Mezirow said, “we’ve seen members of this council and its advisory bodies on social media get threatened, calls for their businesses to be boycotted, and their character slandered for supporting a reasoned alternative that in fact results in a huge bycatch reduction.”