John McCurdy of Lubec, Maine, holds the distinction of having run the last herring smokehouse in the USA. Sit down to talk to him about it, and you’ll find that at age 92, he is still mad about the US Food and Drug Administration shutting him down in 1991. “What happened is, some people in New York City got botulism from smoked whitefish out in the Great Lakes. So, they made a law that all smoked fish had to be eviscerated before they were salted. Well, you know we bought over 100 hogsheads [120,000] at a time, and those boats wanted to unload fast and get back out fishing. There’s no way we could gut those fish.”

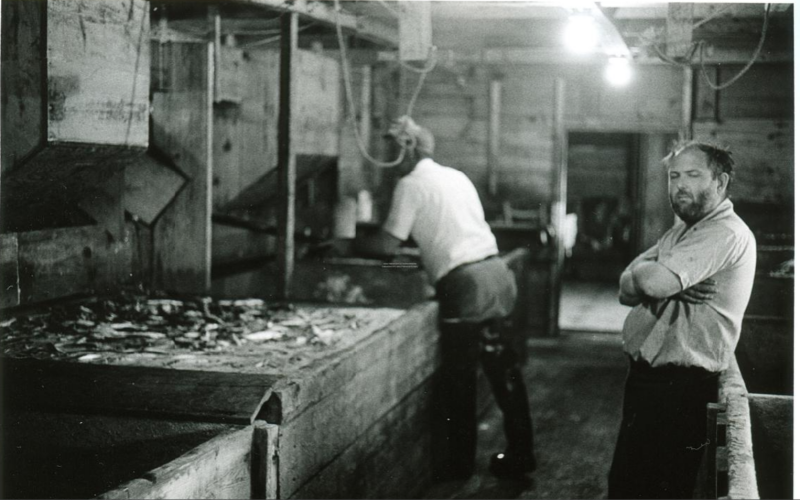

McCurdy’ smokehouse was already a labor-intensive business, with 24 people doing everything from brining the fish, loading the smokehouse, moving fish upward in the smokehouse over the course of an 8-week curing process, and then skinning, boning, and packing it. And it was all hand work, “Artisanal” it would be called today. The workers made the boxes for packing, carefully laid the fish in, and nailed the lids on. Nothing in the entire operation was automated; it relied on human beings using their judgment as to how much brine to soak the fish into when the fish were ready. “If they rattle when you bring them down, they’re ready,” says McCurdy. “We sold 15,000 boxes a year. We sold to Mom & Pop stores, 100 boxes here, a hundred there.”

In 1991, however, the FDA decided that the millions of fish that McCurdy, his father, and his grandfather had been selling for a century were a health hazard. “I took them to a lab myself,” says McCurdy. “They tested them and couldn’t find a spore of botulism. And if they had found it, five days in the brine would have killed it.”

Unfortunately, the FDA’s one-size-fits-all regulation did not leave room for negotiation. McCurdy had to eviscerate the fish or close. In those days, he bought millions of fish every year from purse seiners working the Bay of Fundy, and stop seiners and weir fishermen closer to home. “I’d get a phone call at 2 in the morning, ‘we got your fish,’ and I go down to the smokehouse and start getting the brine tanks ready. At first light, I’d see that boat come around Quoddy Head loaded right down to the rails; oh what a beautiful sight.”

But no more. While most of the seafood Americans consume is imported, and eating local has become a thing, a business that processed American fish and sold it to American markets has been turned into a museum.

“What really got me,” says McCurdy. “Is that about two weeks after they closed us, a woman came down from Augusta to talk about how to create more jobs in Lubec.”