Kicking off a series written by Arni Thomson- History of the Fishing Vessel Owners Association (FVOA), Seattle, WA, Activities from 1914 – 2024

This paper summarizes the origins of the Pacific halibut fishery and its rapid transformation into an industrial fishery that led to the formation of the Fishing Vessel Owners Association (FVOA) of Seattle, Washington, in 1914.

The organization quickly became and remains one of the most effective and durable industrial fishing organizations in the United States. The major focus is a description of the FVOA role in the fishery from 1914 through 2024, a period of 110 years—with only two managers. Description of the fishery relies on the archives of the FVOA, which include F. Heward Bell’s “The Pacific Halibut Fishery the Resource and the Fishery”; and two of Arni Thomson’s manuscripts, “The Pacific Halibut Fishery, 1888 – 1974” a Master’s Thesis; and “The Settlement of Ballard and the Norwegian-American Role in the Development of the Pacific Halibut Fishery”, Nordic Heritage Museum Journal #2, 2005; “NEFCO From Sea to World Markets, The Story of New England Fish Co. Eighty-Fifth Anniversary Edition,” 1953; and the International Pacific Halibut Commission, North Pacific Fishery Management Council and Pacific Fishery Management Council archives.

Historical Overview of the Early Fishery

The coastal Pacific Northwest region comprised of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia and Alaska was a frontier in the 1860s – 1900. Virgin forests and abundant wildlife and fisheries resources characterized the region.

The Indigenous Halibut Fishery

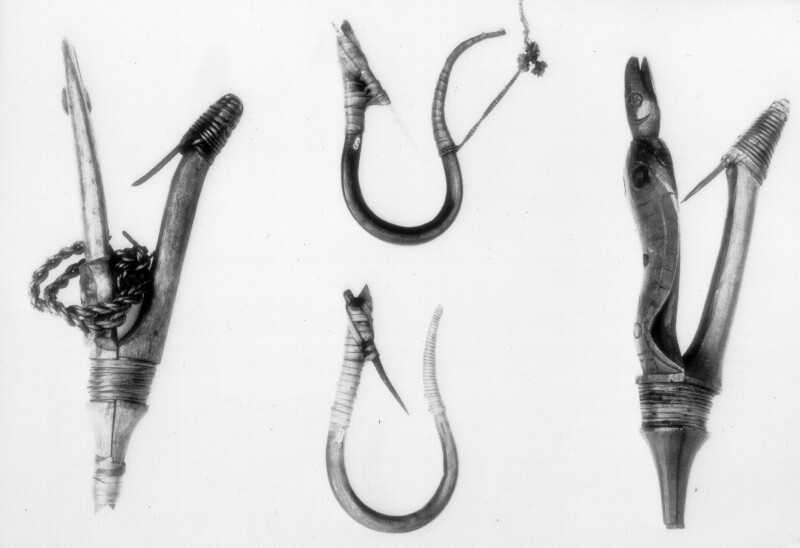

The halibut fishery along the Pacific Coast began with the Indian Nations of the region. With halibut plentiful in inshore and offshore waters of the Northeast Pacific, many tribes of coastal Indians fished halibut for subsistence and it was an important part of their food supply. Tribal groups of the coast fishing halibut were the Cape Flattery Makah near Neah Bay in northwest Washington, the Nootka of the west coast of Vancouver Island, the Kwagiutal of Queen Charlotte Sound, the Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands and south end of Prince of Wales Island the Tsimishian of the Hecate Straight coast of British Columbia and the Tlingit of Southeastern Alaska. Each group often incorporated a distinctive feature in their gear (a gear mark). The coastal peoples generally used the same type of gear, including a specialized circular hook that was difficult for halibut to shake loose. The Mustad company of Norway, studied the design and eventually started manufacturing “circle hooks” that began to be used first in the Pacific albacore tuna fishery and then became the standard hook used in the Pacific halibut fishery beginning in the early 1980s. The circle hook was soon found to greatly increase the “catch per unit of effort” (CPUE) and required the Halibut Commission to consider the change in its mature population estimates.

Early Halibut Fishing Fleets

The vessels that participated in the Pacific halibut fishery have been grouped into a succession of overlapping types that include sailing vessels, steamers, “schooners,” and combination or seine boat-type vesssels.

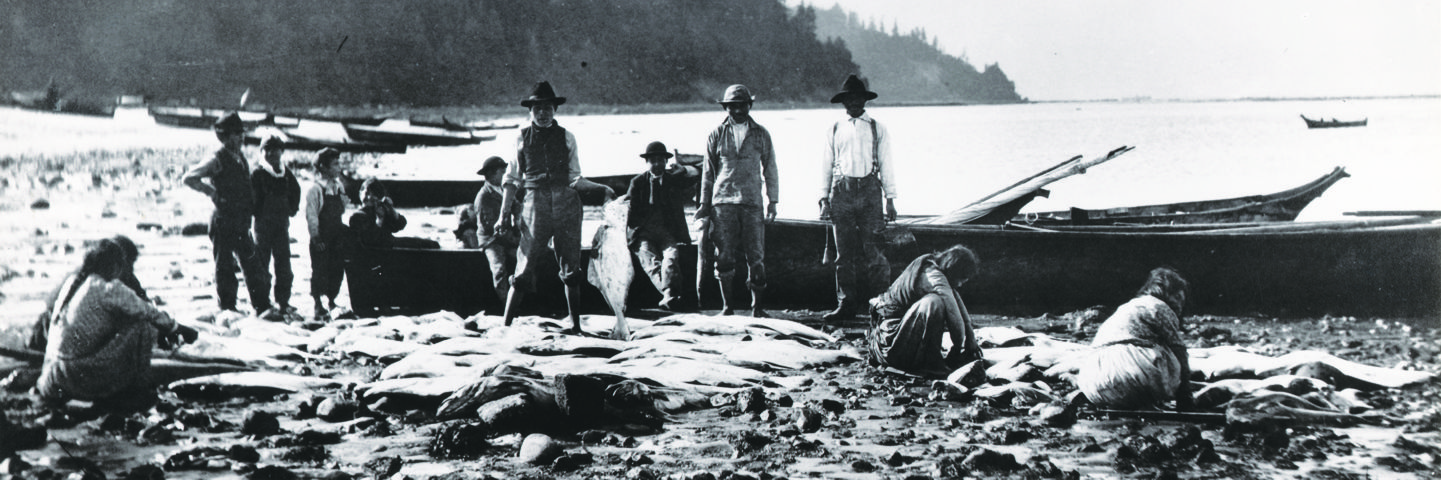

East Coast Origins and The Period of Sail

Early commercial fishing for halibut was carried out by sailing schooners as early as 1870. Sporadic attempts were made to transport iced halibut from the Northwest to San Francisco. The Pacific halibut fishery was just beginning at the time when sail alone was used in the commercial fishery. In the 1880s, a small group of two-man sailing vessels could carry about 3,000 pounds of halibut delivered to local markets of Victoria, Nanaimo, Vancouver, Port Townsend, and other Puget Sound ports. Fish were caught in waters close to the landing ports.

The only vessels of substantial size fishing during the period of sail were the three that sailed from Gloucester around Cape Horn in 1888. The entry of the three vessels into the halibut fishery in 1888 marked the beginning of the commercial Pacific Halibut Fishery. The vessels were the Oscar and Hattie, Edward E. Webster, and the Mollie Adams. They were the typical Gloucester schooner with six dories carried amidships and a crew of about 14. The Oscar and Hattie were 90 feet long and 85 gross tons.

As Bell notes, “Many famous ships have rounded the horn since the time of Ferdinand Magellan in 1520, and much has been said of their exploits. Almost unmentioned have been the innumerable small vessels which with their intrepid crews also braved the dangers of the almost always stormy waters. The Oscar and Hattie was one of the many such ships that made the hazardous passage.”

The Oscar and Hattie left her home port of Swampscott, Massachusetts, on December 11, 1887, commencing a voyage that would seemingly take the three vessels to the ends of the earth in search of halibut.

The Edward E. Webster and the Mollie Adams, owned by Silas Calder, preceeded the Oscar and Hattie with their departure on October 29, 1887. Supplies of fresh halibut were depleted in North Atlantic waters, and accounts of the great abundance of halibut on the Northwest Coast of Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska were a powerful lure to the adventurous seafaring men of New England. They were also attracted by the promise of lucrative pelagic sealing along the Northwest Coast. Chris Johanson of Swampscott, Massachusetts, was the owner and captain of the Oscar and Hattie. The voyage was arduous and took over four months before the three vessels arrived at their new home port of Port Townsend, Washington, 15,000 miles from Swampscott, Maine.

These vessels experienced modest success on trips where halibut was filleted and salted. A Pacific coast fresh halibut fishery, destined for established east coast markets, presented too many problems for vessels depending exclusively upon sail.

In 1888, the Oscar and Hattie landed a fare of 50,000 pounds of halibut in Tacoma, and on September 20, 1888, the first rail car of fresh halibut left Tacoma on the newly completed Northern Pacific Railroad for the east coast, establishing the date upon which the Pacific halibut fishery came into being.

The high cost of ice and sometimes the lack of ice, high freight rates, long distances from the grounds to ports and the difficulties of navigating the narrow fjord-like rocky passages, along with the east coast market’s strong initial resistance to Pacific halibut, ended the sailing episode for the Oscar and Hattie at the end of its second season. (Bell, p. 22). Fortunately, the vessels had been built primarily for pelagic sealing, and this presented a fall-back from halibut fishing. A few sloops and some small schooners continued using only sail in the fishery for several years, but after 1900, all had installed small auxilliary gas engines when available. In 1895, the More was the first to install a gas engine.

The fleet of sloops and small schooners, including East Coast built vessels, with small gas engines was an important factor in the development of the Pacific halibut fishery during the first decade of the twentieth century. It established a core group of independently-owned boats that supplemented the production of the growing fleet of large company owned steamers. Most of the auxiliary-powered vessels were U.S. flag vessels and their operations were centered out of Seattle, with a few vessels from other Puget Sound ports. Very few came from Canadian ports, that portion of the fishery was dominated by the company-owned steamers.

During the summer months, most of the Puget Sound fleet fished the grounds off Cape Flattery and the entire west coast of Vancouver Island. Fishing north of Cape Scott was a rare event. In the fall and winter, many fished the inside waters of Southeast Alaska in the Alexander Archipelago. The catches were boxed with glacier ice, crushed by the crews, and shipped by common carrier on consignment to Puget Sound.

The auxiliary sloops and small schooners were later joined by several larger vessels that had been designed as sailing vessels on the East Coast. They were fitted with gas engines as a primary source of power. According to Bell, they were the forerunners of the typical halibut schooner that was soon to dominate the fishery, but they lacked the characteristic lines.

One such vessel was the Knickerbocker, a large vessel which the New England Fish Company brought around Cape Horn in 1914. The vessel had the lines and the configuration of a downeast sailing ship in the Bank fisheries of the Northwest Atlantic. This wooden fishing vessel was built in Essex, Massachusetts, in 1913, and it was 112.5 feet in length with a gross tonnage of 159 tons and a net tonnage of 101 tons. Upon its arrival in Puget Sound, it was refitted with two 100 h.p. engines. The vessel fished for the New England Fish Co. from 1914 to 1917 with only moderate success. Other smaller auxiliary powered hybrid vessels, built on the East Coast for pelagic sealing were the Carlotta G. Cox, and Pescawha. They were in the British Registry and fished for Atlin Fish Co. of Prince Rupert, a subsidiary of New England Fish Co.

The Pescawha had been built in Liverpool, Nova Scotia, in 1906 for the pelagic seal fishery of the North Pacific which was centered in Victoria B.C. Following the signing of the Tripartite Seal Treaty between Canada, the United States, and Japan and the termination of pelagic sealing in 1911, the Pescawha and several other sealers began fishing halibut.

The Pescawha initially had a 7 h.p. auxiliary engine, and this was upgraded with a 100 h.p. engine when it began fishing halibut. Like the larger Knickerbocker in the U.S. Registry, the converted Canadian sealers were only moderately successful. Another early hybrid schooner was the Seattle-based Idaho, which under Captain T.P. Quinn, discovered the Yakutat Spit spawning grounds in 1913. Most of the hybrids were not technologically adaptable to the needs of the halibut fishery. The steamers and the first of the halibut schooners that were being custom built for the fishery, owned this period.

The New England Fish Company prepares to enter the Pacific Coast halibut fishery

While independent sailing vessels were struggling with startup issues to access the commercial fresh fish market on the East Coast for Pacific halibut, a small group of eleven wholesale fish dealers met in Boston on March 9, 1868 and organized the New England Fish Company, for the purpose of systematically marketing the catch of the halibut fishermen. Following the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, New England fisheries were being developed, and by 1830, Atlantic halibut had become one of the most sought-after varieties of fish. While the fish markets in larger cities were being maintained, methods of buying and selling halibut were unsystematic, and fishermen, dealers, and buyers of fish were all suffering because of the haphazard methods employed. The Civil War, while it brought better prices for fish, called many men away from the trade to the colors, but it also effected important changes for the industry. Some of the fish dealers in Boston, while serving in the army, became impressed with the value of orderly conduct of business and other affairs and resolved to apply lessons learned from the military to their own business.

About this time another important technological development occurred that was favorable to business, Alexander Grham Bell and his scientific associate Thomas A. Watson were successful with their invention of the telephone. It was exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in June of 1876. It is a matter of record that the first money paid for telephone service was paid by the President of the New England Fish Company, Freeman W. Emery and his brother James on May 30, 1877 for the rental of a telephone in the home of each of them for one year. In actuality, their homes were across the street from each other.

In 1884, NEFCO (as the name of New England Fish Company had become contracted for convenience) moved to T-Wharf in Boston, which by then had become the site of operations of Boston’s wholesale fish business.