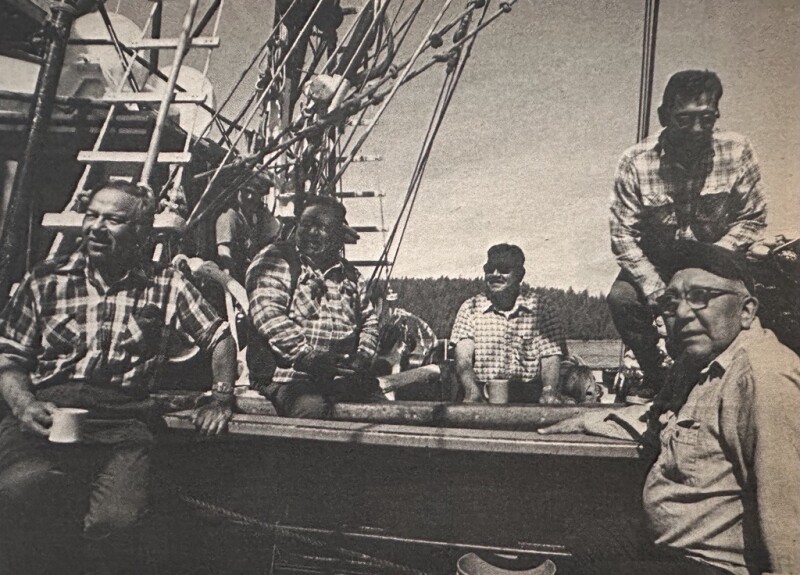

Fishing Back When: Story and photos by William McCloskey Jr. from the 1983 Yearbook of National Fisherman.

Why would anyone who has a choice want to fish for a living, given the cold, wet, uncertainty, danger, muck, dependence on weather for make or break, and general ass-busting hardship?

For a skipper of any sized boat, add the government regulations, ruinous cost of fuel and pressure to earn enough to buy (and make payments on) the latest equipment to stay competitive. The romance of it is all very well when contemplated in front of a warm fire, but it's different when you have to go out every morning.

For many, the answer is simple: They do it to make a living in the way best available to them; they're more or less stuck with it. For a male growing up in a small coastal community with limited options, fishing is often what his dad, brothers, and uncles do.

As a kid, he probably even dreams of the day he'll follow the men to sea and walk big himself. He's lucky if the idea appeals: It may be his only choice, although this has become less so in America than in many other parts of the world.

In the outports of Newfoundland - villages of frame houses set on sea-blown rocks as close to the fish as possible - you'll see nine-year-old boys already strutting in pint-sized rubber boots, grabbing for the lines, pitching cod, virtually caressing the nets as they help where they can to be part of it all.

The Role Models

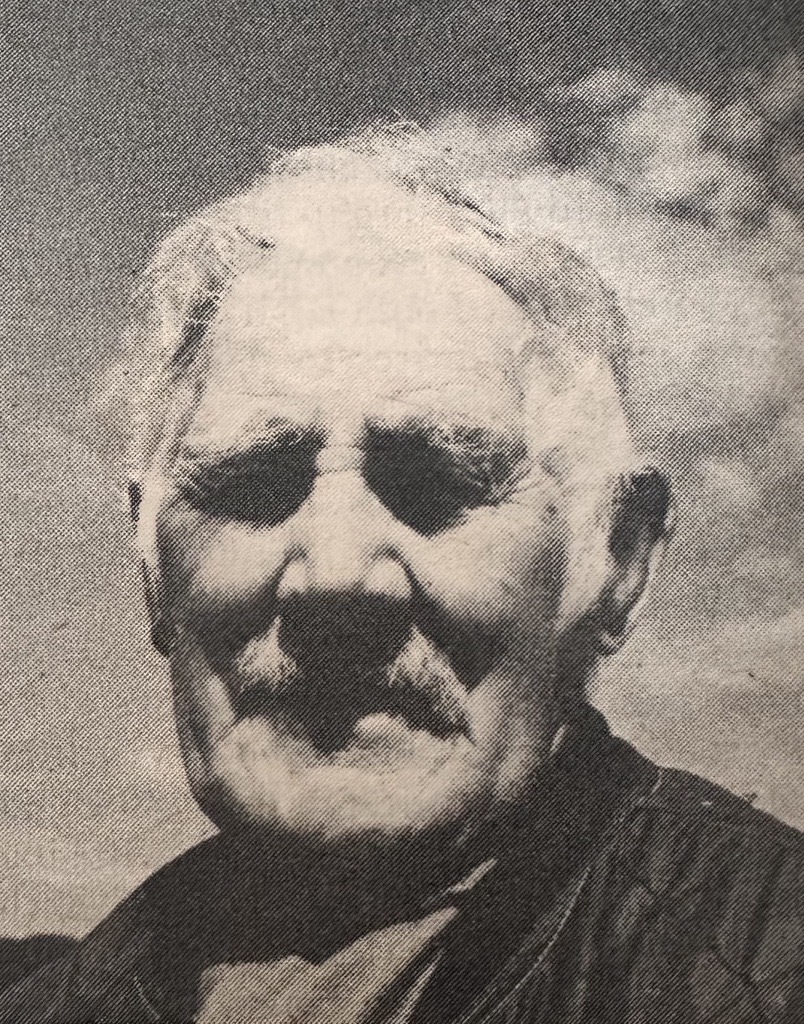

If they looked with the eyes of city kids, they'd see their "fadders" as men weathered old before their time, with fingers missing, hands puffed and sore, and with hurt muscles keeping them awake at night. Instead, what they see are men in whom confident authority comes as second nature, men who are strong, rough, self-reliant, and independent - the sort of men most boys would like to become.

Many of these fishing village kids grow to fill full-sized boots. They go to sea and never in their lives consider being anywhere but with the nets. The same is true for thousands of fishermen's kids in somewhat less isolated communities up and down the U.S. coasts, from New England and Chesapeake Bay/Tidewater, around the Gulf of Mexico, and up along the Pacific.

"Wouldn't have it otherwise. Don't have to answer to anybody but yourself," they say in many ways (deckhands forgetting for the moment the way an easygoing skipper can sometimes become a shouting maniac on the grounds). To understand, you have only to watch the wistful eyes of old men in fishing towns as they follow the boats headed out through the breakwaters. Retired accountants don't yearn that way over old ledgers.

Others born to fishing escape from it as soon as they can. Three decades ago, when Newfoundland became a province of Canada and thus eligible for the amenities of an easier society, there was a great exodus of young men from the outports to the big places like Toronto.

Men were raised with a strong work ethic and forced to learn many skills, as a fishermen must find work enough as carpenters, welders, and the like. But many, many of them later returned to the outports, choosing finally to live as fishermen. 'Twas in their blood.

That's heartwarming stuff, but hardly the whole story. You have only to look at the grimness of the faces on some boats in some fisheries (sample those of men bringing their hauls to the Boston Fish Pier on an icy winter morning) to know that many fishermen are truly stuck and would work ashore if only they could.

Those born to it constitute the core of the world's fishermen. But plenty of North American fishermen have not been trapped at all, nor born to the nets, nor eased back into the family occupation.

They have come voluntarily from all over, including such unlikely places as Kansas and Manitoba - farm kids and city kids, many with a year or two of college — seeking romance, a new lifestyle, a testing experience. Some, in hard times like these, merely want work. All these are valid reasons in a free, mobile society.

They pound the docks, looking for a site or berth. It's not easy in community fisheries, where men prefer fishing with those they know. If some skippers take them aboard as greenhorns - essentially as unskilled labor in an occupation requiring many specific skills - they learn the basics quickly while working hard, or they get off fast.

Those newcomers who choose to stick it out, or who are allowed to, often have a survival experience. In Alaska, where several fisheries are new enough to have no traditional barriers, it may be easier to find a first berth. It is also an easy place to be lost overboard in some of the world's most brutal weather, or to be worn down quickly with the relentless pace, bull labor and 20-hour days. The ones who stick it out need willpower.

From these graduated greenhorns, as well as from the younger generation of the traditional core, have come some of the hardest-driving and most successful fishermen - also some of the most innovative, willing to try new gear, species, and markets. No fisherman makes it without working harder than most men ashore - take this for granted - but the driving innovators are a special breed relatively new to the scene.

Those who are fishermen's kids don't necessarily fish like their daddies did before them. Many are drawn to places like Alaska, where the rules are still fluid and high-priced species are generally abundant.

(Translate that lure into money, at least in part, and forget the weather. Abundance, more than the promise of balmy waters, seems to attract men with fishing in their blood.)

Others stay closer to home to explore and develop new fisheries, especially now that the 200-mile jurisdictions of 1977 have opened opportunities. The new breed are making traditions of their own.

Thus there exist different motivations among those who fish for a living. No single answer — beyond the need for money — tells any part of the whole story. So many different ways to fish, and so many species!

Men pull nets and lines by hand from open skiffs, balancing on a slippery thwart; they trawl, seine, and longline from old gurry buckets that house little more than an engine, single-burner stove, and tight bunks curved along the inside of the bow; they work the gear from boats big enough to have separate galleys and heads, and on near-ships with separate cabins for each hand and with deck machinery that pulls or lifts anything.

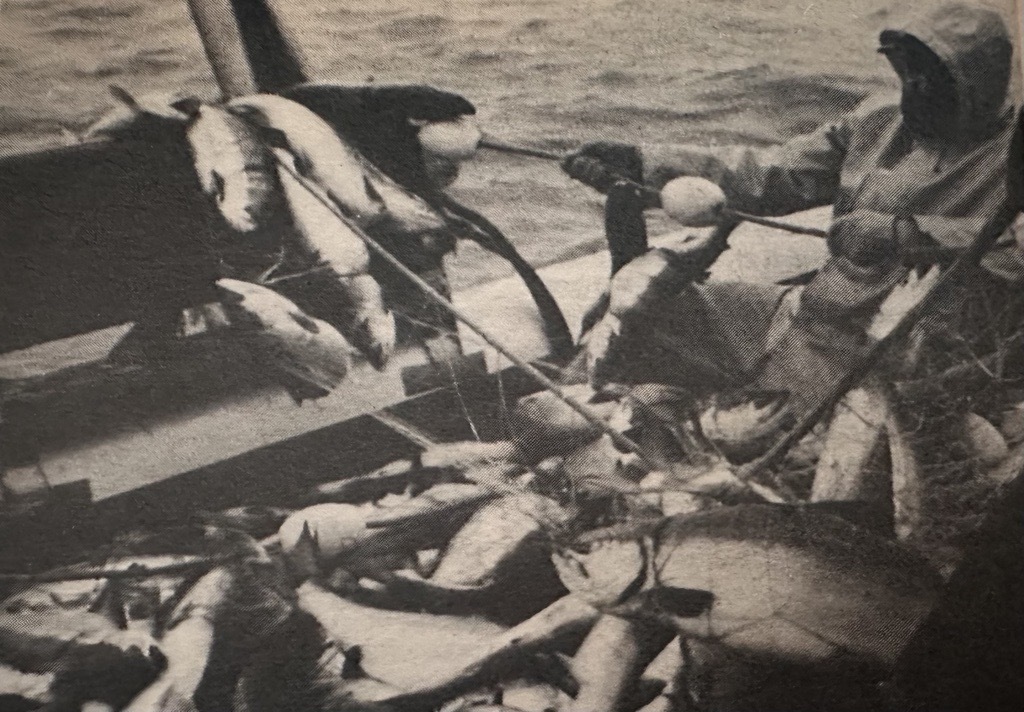

The species they hunt range from slippery cod. that flap around the legs and must be gutted at once, to thousandfold herring and menhaden and capelin that travel to and from the hold by suction hose without ever touching a man, to piles of blackened oysters dredged aboard to be culled apart from sea-floor rocks, to huge tunas and halibuts and swordfish that must be fought before being hefted into storage like so many concrete blocks, to small snapping crabs handled gingerly from pot to closed basket, to sluggish purple king crabs the size and weight of old-fashioned alarm clocks, to little pandalid shrimp that need to be hosed and shoveled like gravel, to big brownie shrimp sorted one by one from piles of "trash," to glorious silvery salmon that accumulate a stinking gurry in the few hours before you hand-pitch them from hold to brailer, to tutti-fruitti fish in all sizes, either separated for food or allowed to mush together for meal.

Fishing is Unique

Many men (and some women) fish for a living because it is the thing they want most in the world to do. The work resembles no other. It depends on the forces and cycles of nature (so does farming), it involves seeking out living creatures for the food they provide (so does hunting), and it requires working outdoors (so do surveying, ditch digging, and geology).

Unique among ways to make a living, it depends on pursuing and harvesting a product that remains invisible, unassessable, until its capture. Call it unique also - stirring, in an atavistic way - that fishing is one of man's oldest and most basic occupations, and that it sometimes requires the facing of primal forces as no other.

Within the endless repetitions of setting and hauling gear and processing the haul, there always exists the chance for variety.

The unexpected is everywhere: in squalls, sunrises, full nets and empty ones, breakdowns that challenge the ingenuity, sparkling clear days when each breath is a pleasure.

There are terrible days, ice-blown and wet, when you drag and pull and haul, and nothing comes in but seaweed clotted around the twine or webbing ripped by rocks, nothing anywhere in the sea to pay for the fuel and grub, much less the bills at home.

Then there are the days, now and then, when nets or pots or lines come in exploding with life. You can hardly walk on deck for the abundance around your legs — you have to block the scuppers to keep some from escaping. The exuberance of this never wanes. Old fishermen can confirm it.

You shout, dance, laugh, throw things - all the while knowing that now, instead of a stretch-out for a sore back between sets, you'll gut, cull, shovel, ice, bait, pick and mend through the day and the night and all the next day, near-dead with good fortune. Is it only the money you'll get that drives you? Some would say so, to avoid being called nuts.

Out of it comes a pride in self-sufficiency. The land recedes each trip out, and you're on your own, without the stress of highway snarls or the comfort of a fenced yard. On the worst of days, you start and you finish tired, cold, hungry, aching.

Sometimes you only keep going by kicking yourself, or by promising that this is the final trip, and never again. You mean it desperately, grimly. (Sometimes you really do mean it.)

Then you get ashore, warm up, grog up, see the loved ones, sleep in for a day or so, and ... suddenly you feel housebound and chained in a world that's too orderly. Look at those high-smelling little prisons of boats moored at the pier, bobbing with the tide, the hosed-down oilskins swingly stiffly from hooks under the housing, the instruments of torture and challenge called gear waiting for somebody who can make them haul fish again from the unknown sea, bust or bonanza.

Oh hell. If you don't understand inherently why men give up their comforts to go fish for a living and find themselves yearning after the boats when they've been away for long, it's likely that no words will tell you. Best stay ashore with the other clock-punchers.