Scores of vessels passing through mandatory and voluntary slow zones exceeded speed limits in the approaches to Chesapeake Bay in the days before an endangered North Atlantic right whale washed up dead Feb. 12, the victim of a vessel strike, according to the environmental group Oceana.

The 20-year-old whale – one of a population. now estimated at only around 340 animals – was found near Virginia Beach, Va., and investigators said the carcass showed injuries from a vessel strike.

The Virginia Beach stranding happened as opponents of offshore wind projects pointed to other Mid-Atlantic whale strandings this winter – most of them humpback whales – to argue that survey work must be suspended.

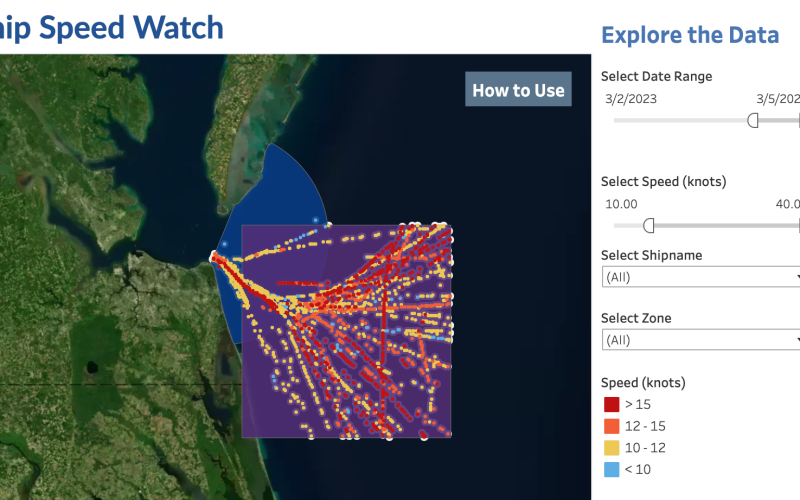

Oceana, which has pushed for strict vessel speed limits to protect whales, said it has evidence from Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracks to show speed limits set by the National Marine Fisheries Service are regularly exceeded and endangering whales.

The group cited its Ship Speed Watch program, which uses AIS data from Global Fishing Watch, an independent non-profit founded by Oceana in partnership with Google and SkyTruth. The system compiles data from global vessel tracking services.

Looking at results from Feb. 1 to Feb. 11, Oceana says its analysis shows “nearly seven out of 10 boats traveled above the speed limit of 10 knots through either mandatory or voluntary slow zones.”

About half of those vessels exceeded the 10-knot maximum speed in the mandatory slow zone close to Chesapeake Bay, according to Oceana. In the four days before the right whale was found on the beach, “more than 75 percent of the boats (77 boats) did not comply with the mandatory or voluntary speed limits between February 8 and 11,” the group says.

The Oceana summary uses the term “boats” generically for vessels covered by the NMFS speed limit advisories, which now apply to vessels 65 feet or longer. The agency proposes to lower that requirement to vessels of 35 feet, and extend the areas covered by the advisories.

That rule change is being fought by vessel operators, ranging from ferry companies to charter and party boat fishing captains. Oceana and other environmental groups petitioned NMFS to make it an emergency rule, but were rejected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Jan. 20.

“Speeding boats and slow swimming whales are a recipe for disaster, but a preventable one. Current vessel speed limits are ineffective and made worse by the fact that they aren’t even properly enforced,” said Gib Brogan, a campaign director at Oceana. “NOAA must immediately issue the final vessel speed measures before more whales needlessly die. These speed limits also need robust enforcement and accountability for those breaking the law.”

Earlier analyses by Oceana and NOAA’s own experts used AIS tracking data to show speed limit advisories have limited effect on ship operations in and out of U.S. East Coast ports.

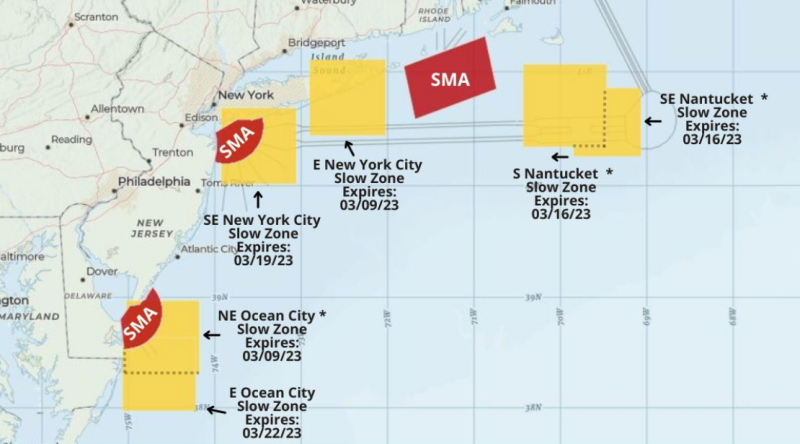

The endangered right whale is NOAA’s primary species of concern with speed advisories, now in effect from Massachusetts to Virginia.